Atreus was the mythical Greek king of Mycenae. He is perhaps best known for being the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus, two heroes of the Trojan War, as well as for the terrible curse placed upon his family. This was a hereditary curse, plaguing the family for five generations with a vicious cycle of murder and revenge.

The curse of the House of Atreus began when its founder, Tantalus, offended the gods by serving them a feast made of the dismembered remains of his own son, Pelops, in an attempt to test their omniscience. It continued with the rivalry between Atreus and his brother Thyestes that blossomed into a bloody feud, and it afflicted the next generation as well, with the murder of Agamemnon by his own wife. The curse did not end until Atreus' grandson Orestes avenged Agamemnon's murder and was absolved from all guilt by the gods.

The story of Atreus and his heirs made excellent dramatic material for ancient Greek and Roman literature, as seen in the trilogy known as the Oresteia written by Greek tragedy playwright Aeschylus (c. 525 to c. 456 BCE) and the tragedy Thyestes written by Seneca (4 BCE to 65 CE). The members of the House of Atreus are referenced in many different sources of Greek mythology, with Atreus' descendants being collectively known as Atreidai, the plural form of the patronymic name Atreides.

Origins of the House of Atreus: Tantalus & Pelops

The founder of the House of Atreus, and the man to bring about its curse, was Tantalus. King of Sipylus and a son of Zeus and the nymph Plouto, Tantalus was an intimate of the gods and was allowed to attend the Olympian banquets of nectar and ambrosia. Despite this favored status, Tantalus had a mischievous mind and wondered how omniscient the Olympian gods really were.

He was soon to put this question to the test. While preparing to host the gods at a banquet of his own on Mount Sipylus, Tantalus realized he did not have enough food in his stores for his divine guests. Deciding this was a perfect time to learn if the gods really did know everything, he killed his son Pelops, diced him up, and added the pieces to a stew. When he served this meal to the gods, most of them were not fooled by what was in the dish and were horrified and disgusted. Only Demeter, distracted by the recent abduction of her daughter Persephone by Hades, ate from the stew, consuming Pelops' shoulder. An enraged Zeus punished Tantalus for this crime, killing him and condemning him to eternal torment in the afterlife, where he suffered an unending and unquenchable thirst. From Tantalus' crime came the first curse to befall the House of Atreus, although it would not be the last.

Following Tantalus’ punishment, Zeus resurrected Pelops, replacing the shoulder eaten by Demeter with one made of ivory. Upon laying eyes on the revived Pelops, Poseidon fell in love with the youth's radiant beauty and whisked him off to Mount Olympus. Pelops stayed there with the god for a time before setting off to seek his own fortune. As a parting gift, Poseidon presented Pelops with a winged chariot that could run across the sea without wetting its axles.

Pelops eventually arrived at the court of King Oenomaus of Pisa, wishing to marry the king's daughter, Hippodamia. However, Oenomaus had been warned in a prophecy that he would one day be killed by a son-in-law and had designed a scheme to ensure that his daughter would never marry. He challenged each of her would-be suitors to a chariot race to the Isthmus of Corinth. If the potential suitor won the race, he would be given the prize of Hippodamia's hand in marriage. If Oenomaus won, however, the suitor would be killed. The catch was that Oenomaus' chariot was pulled by horses given to him by Ares, and he was always able to outrun the suitors. In this way, he killed twelve of them before Pelops' arrival, nailing their severed heads to his house.

When Pelops arrived to take part in this challenge, his beauty made him catch the eye of Hippodamia herself who, like Poseidon before her, fell in love with him. Resolving to help Pelops win, Hippodamia went to Myrtillus, her father's servant and a son of Hermes, and asked him to sabotage Oenomaus' chariot. Myrtillus, who had been in love with Hippodamia himself but had not dared to race Oenomaus for her hand, agreed to help, wishing to please her. On the day of the race, he replaced the bronze linchpins on the king's chariot with false ones made of beeswax. When the race began, Pelops easily overtook Oenomaus in Poseidon's chariot. As the king rushed to catch up, the wheels of his chariot fell off, and he was either killed in the accident or by Pelops after he had crossed the finish line.

Afterwards, Pelops, Hippodamia, and Myrtillus drove in Poseidon's chariot across the sea, stopping at a certain island so Pelops could fetch his new bride some water. When he returned to the chariot, he found Hippodamia in tears, claiming that Myrtillus had tried to have sex with her. Myrtillus defended himself, claiming Hippodamia had agreed to let him lay with her on her wedding night as the price for his assistance. Enraged, Pelops slew Myrtillus who laid a curse on Pelops and his family with his dying breath. This curse, combined with the one laid on Tantalus for his crimes against the gods, would plague Pelops' descendants for generations.

Atreus, Thyestes, & the Golden Lamb

Pelops became a great king, ruling over much of the southern Greek peninsula that would eventually bear his name, the Peloponnese ("Island of Pelops"). He and Hippodamia had many children together, although the happiness of their marriage did not last. With the nymph Astyoche, Pelops had an illegitimate son named Chrysippus, who he soon favored over all his children with Hippodamia. Fearing that Pelops would choose Chrysippus as his heir over any of her own sons, Hippodamia conspired to kill the boy. In some versions of the story, she killed Chrysippus herself while in others she coaxed two of her sons, Atreus and Thyestes, to do it for her.

Pelops, learning of the culprits behind Chrysippus' murder, banished Hippodamia, Atreus, and Thyestes. Overcome by grief, Hippodamia hanged herself, but Atreus and Thyestes made their way to the city of Mycenae, where their rivalry blossomed.

The trouble would start when Hermes, intent on getting revenge on the descendants of Pelops for the murder of his son Myrtillus, placed a golden lamb in Atreus' flock. Atreus found the lamb and decided to keep its golden fleece, despite having made an earlier vow to sacrifice the finest of his flocks to Artemis. He kept the vow in part by sacrificing the lamb's flesh, but he kept the fleece locked away in a chest. Atreus wasn't shy about his newfound treasure and could often be found boasting about his golden lamb in public.

His brother Thyestes, always jealous of Atreus, began to plot on how he could get his hands on Atreus' treasure, and soon came up with an answer. Atreus' newlywed wife, Aerope, had fallen in love with Thyestes and had been trying to seduce him. Thyestes agreed to have an affair with her, on the condition that she steal the chest containing Atreus' lamb and give it to him. Aerope did as he wished and gave Thyestes the chest, little knowing that Artemis had placed a further curse on it because of Atreus' failure to sacrifice the whole lamb.

Around this time, the people of Mycenae were in need of a new king. Having been advised by the Delphic Oracle to choose a son of Pelops to rule them, the Mycenaeans invited Atreus and Thyestes to a council hall meeting to determine which of them should become king. Ever boastful, Atreus declared that the owner of the golden lamb should be given the scepter. He was surprised when Thyestes agreed, going so far as to ask Atreus to declare this publicly. Once Atreus had repeated this claim in front of the entire city, Thyestes produced the chest containing the golden lamb and was himself declared king of Mycenae.

Zeus, however, was displeased with this outcome, wishing for Atreus to become king. He sent Hermes down to Atreus, telling him that he should reach an agreement with Thyestes, that should the sun ever reverse its course and set in the east, Thyestes would abdicate his throne in favor of his brother. Atreus did as he was told, and went to Thyestes with the proposal. Laughing at the absurdity of such a suggestion, Thyestes agreed and promised that he would abdicate if that impossible event were ever to occur. Following this agreement, Zeus ordered Helios to reverse his course in the sky, and "for the first and last time, the sun set in the east" (Graves, 407). Thyestes was therefore forced to abdicate to Atreus who made it his first order as king to banish his brother from the city.

Rivalry Between Atreus & Thyestes

After he had banished Thyestes, Atreus learned of the adultery Aerope had committed and vowed to take further revenge. He sent a herald to his brother, faking reconciliation and asking Thyestes to return and help him run the kingdom as a co-ruler. As soon as Thyestes accepted this offer, Atreus murdered Aglaus, Orchomenus, and Callileon, Thyestes' three sons, slaughtering them on the altar of Zeus where they had sought refuge. He then dismembered them and boiled them in a cauldron.

When Thyestes arrived, Atreus treated him to a magnificent feast in his honor, in which he was served a stew made with the remains of his sons. After Thyestes had eaten heartily, Atreus had a second dish brought out, which contained the severed heads, hands, and feet of Thyestes' sons. Horrified, Thyestes fell back, vomiting, and swore revenge on his brother before Atreus exiled him a second time.

Finding himself banished again from the kingdom, Thyestes went to consult the oracle and was told that he must father a son on his own daughter, Pelopia. Only a son born of such incest would be able to kill Atreus. Willing to pay any price for his revenge, Thyestes did as commanded, appearing in disguise before Pelopia and seducing her. Atreus, meanwhile, had been advised by the oracle to recall Thyestes from exile, or else face the consequences of his crime. In his search for his brother, Atreus came across Pelopia, who he assumed to be the daughter of a local king. Atreus fell in love with her, and they were soon married. When Pelopia bore Thyestes' son, Atreus assumed the child was his. The boy was named Aegisthus, or "goat-strength," since he was suckled by a goat, and he was raised in Atreus' palace.

As time went on, Atreus became paranoid of his brother's whereabouts and sent his sons Agamemnon and Menelaus to track him down. They found Thyestes and brought him back to Mycenae, where he was thrown into the dungeon. Once Atreus heard of this, he commanded Aegisthus to go into the cell and kill Thyestes, even though Aegisthus was still a young boy. Going down to the dungeons to commit the deed, Aegisthus was quickly overpowered by Thyestes who promised he would spare the boy if he did what he asked.

Thyestes' first request was for Aegisthus to get his mother and bring her down into the cells. The boy did as he was told and brought down Pelopia who embraced her long-lost father with joy upon seeing him. Her joy would quickly turn to horror when Thyestes next admitted that he was the father of Aegisthus. Upon this realization, Pelopia seized the sword Aegisthus had been given to kill Thyestes and killed herself with it. Thyestes then gave Aegisthus his final request, ordering him to murder Atreus. Aegisthus again did as he was told. Upon leaving the dungeon, he found and slew Atreus. Thyestes then retook the throne, although his reign would not last long. Atreus' son Agamemnon would soon wrest the kingdom from his scheming uncle, claiming the title of king of Mycenae for himself and sending Thyestes into exile a third and final time.

The Murder of Agamemnon & Vengeance of Orestes

The curse afflicting the House of Atreus did not end with Atreus' death but went on to afflict his children. Known as the Atreidai, Atreus' sons Agamemnon and Menelaus both played significant roles in the Trojan War, which began when Menelaus' wife Helen was abducted by Paris. While the brothers were off in Troy, Agamemnon's wife, Clytemnestra, began an affair with Aegisthus, who had returned to Mycenae from exile.

By this point, Clytemnestra had no reason to remain loyal to Agamemnon. Prior to going off to Troy, Agamemnon had sacrificed his and Clytemnestra's daughter, Iphigenia, in order to appease the goddess Artemis and secure safe passage across the sea for his army. When the war ended, Agamemnon came home with his new concubine, the prophetess Cassandra. This proved to be the last straw for Clytemnestra.

Preparing for a great banquet to celebrate his return home, Clytemnestra drew up a bath for Agamemnon. When he was climbing out of the tub, she put a purple robe on him with no opening for the head. While he was tangled up in the robe, Clytemnestra, or alternatively her lover Aegisthus, stabbed him to death. After killing her husband, Clytemnestra decapitated the corpse before running out to kill Cassandra as well. Meanwhile, as Aegisthus' men slew Agamemnon's soldiers in the palace, Aegisthus and Clytemnestra claimed the kingdom for themselves.

Agamemnon had one son, Orestes, who went into exile following his father's murder, smuggled out of the palace by his sister Electra. Growing up in exile, Orestes knew that it was his duty to avenge his father, yet he was torn, as matricide was considered a grave sin. Trying to decide whether to avenge his father or spare his mother, Orestes visited the Delphic Oracle to ask whether or not he should kill his father's murderers. Apollo's answer was that it was his duty to avenge his father, telling him:

If [Orestes] neglected to avenge Agamemnon, he would become an outcast from society, debarred from entering any shrine or temple, and afflicted with a leprosy that ate into his flesh, making it sprout white mold. (Graves, 420)

Upon receiving Apollo's answer, Orestes traveled back to Mycenae where he killed both Aegisthus and his own mother, Clytemnestra. For many years afterward, he wandered the land, guilt-ridden and driven to madness by the furies that pursued him for his unholy crime of matricide. Eventually, he was told by Apollo to go to Athens, where he would stand trial before the Areopagus, a council presided over by Athena herself. The council ruled in his favor, absolving him of any guilt. This verdict brought an end to the curse of the House of Atreus after five generations.

Atreus in Literature and Outside of Myth

The dramatic story of the curse of House Atreus comes down to a modern audience through several works of ancient Greek literature and Roman plays. Aeschylus' Oresteia, a trilogy of three tragedies, tells the story of Agamemnon's murder and Orestes' vengeance. Later, writing in the 1st century CE, Seneca penned the tragedy Thyestes concerning the tale of Atreus feeding his brother the remnants of his sons. William Shakespeare's (1564-1616) tragedy Titus Andronicus, which also concerns a parent being served meals made of their children's flesh, may have been influenced by Seneca's tragedy. The House of Atreus also features in modern literature. In Frank Herbert's (1920-1986) science fiction franchise Dune, the fictional House Atreides claims ancestry from the original House of Atreus.

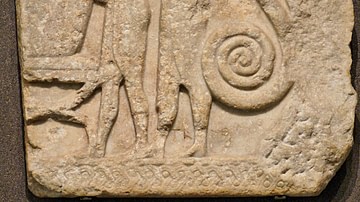

Just as the historicity of the Trojan War remains a subject of debate among scholars, so too does the existence of any historical person who could have been the inspiration for the Atreus of myth. A tomb located in Mycenae, Greece, is connected to the mythical figure by name. Known as the Treasury of Atreus or, alternatively, as the Tomb of Agamemnon, the monumental tomb was constructed during the Bronze Age and perhaps held the remains of a sovereign. However, the structure, built around the 14th century BCE, would have been constructed too early for it to be connected to either of its namesakes.

Some scholars have also considered the possibility of the mention of Atreus in ancient Hittite records. A Hittite text known as the Indictment of Madduwatta describes multiple battles between Greek and Hittite forces, with the Greeks led by a man referred to as Attarsiya. The record claims that Attarsiya was a man of Ahhiya, or Achaea, and went on campaign with a hundred chariots. It has been suggested that the name Attarsiya could have been the Hittite rendering of the name Atreus.

Conclusion

The story of Atreus and his dynasty is a cycle of murder, deceit, incest, and revenge. A horrible infliction brought about by the offensive crime of Tantalus against the gods, it is only natural that the curse did not end until the gods themselves absolved Tantalus' descendent, Orestes, from guilt. It is not difficult to see why the story of Atreus and his heirs became a popular subject for Greek drama, as it serves as a dramatic cautionary tale to the dangers of revenge.