The Attalid Dynasty ruled an empire from their capital at Pergamon during the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE. Fighting for their place in the turbulent world following the death of Alexander the Great, the Attalids briefly flourished with Pergamon becoming a great Hellenistic city famed for its culture, library, and Great Altar. However, the Attalids' short-lived dynasty came to an abrupt end when mighty Rome began to flex its muscles and show greater ambition in Asia Minor and beyond.

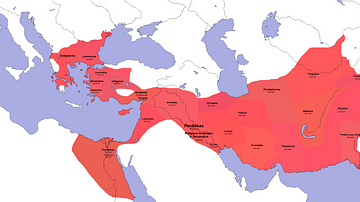

With the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, the empire he created was left without leadership – no heir and no successor. Out of a number of possible options, the immediate solution reached by his loyal commanders was to divide the kingdom among themselves. The young general and bodyguard Lysimachus received the strategically valuable province of Thrace, a small kingdom located along the Hellespont. The Wars of the Diadochi brought him into a power struggle for lands in both Asia Minor and Macedon. His thirst for power enabled him to build alliances with a number of his fellow 'kings' and even marry the daughter of Ptolemy I of Egypt, Arsinoe II. Unfortunately, his death at the Battle of Corupedium in 281 BCE left him without an heir and his throne vacant. His rich territories in Asia Minor, most importantly Pergamon, fell to the Syrian king Seleucus I Nicator. However, a new dynasty would soon emerge and eventually wrestle control away from the Seleucids – Pergamon would shortly become an important power along the Aegean Sea under the guidance of the Attalids.

Philetaerus: Founder of the Empire

Little is known of the early life of Philetaerus. Possibly of Macedonian origin, he was the son of Attalus and Boa, a native of Paphlagonia. While there is some disagreement among historians, his adopted son, Eumenes I, always considered Philetaerus to be the true founder of the Attalid Dynasty. Originally, he served under the Macedonian commander Antigonus I the One-eyed until, in 302 BCE, when he deserted Antigonus amid the growing tension among the various kings and joined the Thracian sovereign Lysimachus. After the death of Antigonus in 301 BCE at the Battle of Ipsus, he was rewarded for his loyalty by being appointed to oversee the king's treasury situated in the Asia Minor city of Pergamon. Regrettably, when Lysimachus, at the urging of his Egyptian wife Arsinoe, executed his only son Agathocles on the trumped-up charge of treason, Philetaerus, along with several other loyal commanders, abandoned Lysimachus and joined Seleucus I – Philetaerus made sure to hand over the treasury and Pergamon to the Seleucids. After the death of Lysimachus at the hands of the Seleucid forces, Philetaerus assumed control of Pergamon. He would govern there, although still under the umbrella of Seleucus I, from 282 to 263 BCE.

During his two decades on the throne, Philetaerus was able to both expand his territory into the Caicus valley as well as defend it (278-276 BCE) against the neighboring Galatians, a people to the east of Pergamon. Instead of waging war, his successors would occasionally pay to keep them away. Although there is no substantial proof, history depicts him as a eunuch. While there is little evidence as to how this condition arose, his family may have chosen that path because it often enabled a person to obtain a high position at court. Under his guidance, and that of his successors, the city and territory of Pergamon would become a Hellenistic showcase.

Despite being located in Asia Minor, Pergamon was, by definition, a Greek city identifying with its neighbor Athens across the sea with the city even adopting the goddess Athena as its presiding deity. She was its protector in times of battle, earning the name 'Nikephoros' or "victory bearer". While the Attalids may have adopted the civil organization of Athens, the king would continue to stand outside the constitution, maintaining the power to appoint the city's magistrates. Since Philetaerus was unable to have children, his adopted nephew, Eumenes I, succeeded him in 263 BCE, serving until 241 BCE. It was Eumenes who proposed a break from the control of Seleucids. After defeating the successor to the Seleucid Dynasty, Antiochus I, at Sardis, Eumenes expanded his territory into northwestern Asia Minor by absorbing Mysia and Aelis as well as Pitane.

Attalus: Founder of the Dynasty

Having no children of his own, Eumenes I was succeeded by his nephew and cousin Attalus I (241-197 BCE), who would assume the title of 'Soter' or 'Savior'. It would be Attalus who would be credited by most historians with founding the kingship of the Attalids – although he personally gave credit to Philetaerus. Since the defeat of Lysimachus, the Seleucids had never been able to maintain control over their Asia Minor territories, and it was for this reason, that the territories of Pergamon, Bithynia, Nicomedia, and Cappadocia emerged into independence. Like his predecessor, Attalus was able to expand his small empire, although he would later relinquish much of this conquered territory to Seleucus II (223-212 BCE). Like his predecessor, he was also able to protect Pergamon against the menacing forces of the bordering Galatians.

It was Attalus I who was instrumental in establishing positive relations with the Roman Republic and involving them in the First Macedonian War. He was also influential, along with the island of Rhodes, bringing Rome back to Greece to wage war against Philip V of Macedon – at the time Rome was recovering from the Second Punic War with Carthage. In the Second Macedonian War (200-197 BCE), Philip V had set his sights on expanding his power into Greece and the Aegean, threatening the Achaeans, Pergamon, and Athens. After a bitter fight, he eventually was forced to make peace and relinquish all conquered lands in Greece, Thrace, and Asia Minor. Unfortunately, before the peace agreement could be signed, Attalus I died at Thebes from a stroke in 197 BCE, and his body was returned to Pergamon. Eumenes II (r. 197-159 BCE), the eldest son of Attalus and Apollones, assumed power and immediately continued his father's war only this time against the son of an old enemy, Antiochus III of Syria.

Relations with Rome

The heir to the Seleucid Dynasty longed to reclaim his family's lost territory in Asia Minor. After an appeal from the Attalids, Rome urged Antiochus to withdraw to Syria; however, instead, he attacked Rome's ally, Greece. After suffering a defeat at Thermopylae, he fled to Asia Minor where he was engaged and defeated at the Battle of Magnesia in Lydia (189 BCE). In the battle, Eumenes' forces drove Antiochus to retreat, causing his elephants to run wild. Antiochus had incorrectly assumed his scythed chariots would cause panic among the Romans, but Eumenes, instead, wisely sent his cavalry, Cretan archers, and light-armed slingers against the charging horses. The Syrian forces fell susceptible to the Roman army under the leadership of Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus. The resulting Peace of Apamea crippled the Seleucid Empire by forcing Antiochus III to pay reparations to Eumenes (he would become extremely wealthy) and withdraw from Asia Minor; the territory north of the Taurus would be split between Pergamon and Rhodes. Rome would later intervene in Eumenes' wars against Bithynia (187-183 BCE) and Pontus (183-179 BCE).

Oddly, an old enemy of Rome from the Second Punic War reappeared in the war with Bithynia. The old Punic commander Hannibal Barca had initially sought refuge with Antiochus III after his exile from Carthage but quickly fled to Bithynia. Although he would win a naval victory over Eumenes, the subsequent peace agreement called for the release of Hannibal to the Romans. Refusing to surrender, the old commander reportedly committed suicide by taking poison in 182 BCE.

Pergamon Flourishes

Afterwards, Eumenes II (also calling himself Soter) went on a building program in Pergamon, erecting the Great Altar and establishing a massive library, second only to Alexandria. In the War of the Brothers, he helped Antiochus IV succeed to the throne of Syria after the death of his brother Seleucus IV (175 BCE). Unfortunately, however, his efforts to bring Rome into another Macedonian war caused him to fall into disfavor with the Romans, especially the Roman Senate. Supposedly, he was to keep Rome informed of the actions of Perseus, the successor of Philip V of Macedon. When Eumenes II traveled to Rome (167-166 BCE), the Roman Senate would not receive him, claiming they no longer received kings. Apparently, his enemies in Rome maintained he had planned to abandon Rome in favor of Perseus if the price was right. To Rome, the king had already demonstrated far too much independence and power, especially after he provided aid to Antiochus IV and made war with Bithynia. Apparently, Rome did not appreciate any attempt to diminish their influence in Asia Minor.

Attalus II & III

Attalus II Philadelphus ('brother-loving') was the second son of Attalus I, and at the urging of Rome, he became co-ruler with his brother, serving from 160 to 138 BCE. He had functioned as both a commander under Eumenes II against Antiochus III as well as the war opposing the Galatians. He had also served as a diplomat to Rome where he fell into favor with the Romans. After his brother's death in 159 BCE, Attalus assumed sole control of the throne, marrying his brother's widow Stratonice and adopting his nephew, the future Attalus III. During his reign, he would maintain close ties with Rome, recognizing their supremacy. His armies supported Nicomedes II of Bithynia and Alexander Balas in Syria but opposed Andriscus in Macedon. While continuing his brother's building program at home, he founded the cities of Philadelphia in Lydia and Attaleia in Pamphylia. Unfortunately, his adopted son, Attalus III (r. 138-133 BCE), would be the last Attalid king. Considered by many to be brutal and unpopular, he was disinterested in public life and relinquished control of Pergamon to Rome. Although there was another claimant - a supposed illegitimate son of Eumenes II named Eumenes III Aristonicus – the dynasty came to an abrupt end.

Unlike the Ptolemaic Dynasty and the Seleucids, the Attalid Dynasty lasted barely a century and a half with much of that under the leadership of a father and his two sons. The family had gained power over Pergamon after the death of Lysimachus, eventually freeing themselves from the rule of the Seleucids. Although Pergamon lay in Asia Minor, the city and province were, by any definition Greek, identifying with the city of Athens, even adopting Athena as their deity and protector. However, a series of long wars against Macedon and Syria brought the expanding Roman Republic onto the scene. After defeating Carthage in the Punic Wars, the Roman Republic had set its sights eastward to Greece and Asia. In the end, Pergamon, under the poor leadership of Attalus III, surrendered without incident to Rome. The short-lived dynasty was no more.