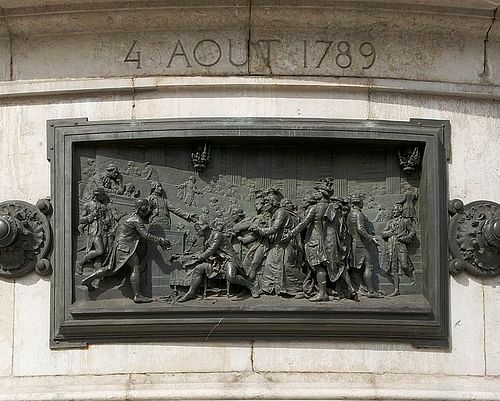

The decrees of 4 August 1789, also known as the August Decrees, were a set of 19 articles passed by the National Constituent Assembly during the French Revolution (1789-1799) which abolished feudalism in France and ended the tax exemption privileges of the upper classes. Although not without flaws, the passage of the decrees was a significant achievement of the Revolution.

The National Assembly, which had been formed from the three estates of pre-revolutionary France during the Estates-General of 1789, sought to prove its dedication to the people and cement the accomplishments of the Revolution. In a state of patriotic fervor, noble deputies renounced their privileges, with others going so far as to demand the abolition of tithes and a new judicial system where all citizens would be equal before the law.

Although many of the articles did not immediately go into effect, the decrees as a whole had a major impact on the destruction of France's oppressive Ancien Régime and paved the way for future developments in equality and human rights.

Prelude: The Twilight of Feudalism

French historian François Furet summarizes the significance of the night of Tuesday, 4 August 1789 as such:

[The date] marks the moment when a judicial and social order, forged over centuries, composed of a hierarchy of separate orders, corps, and communities, and defined by privileges, somehow evaporated, leaving in its place a social world conceived in a new way as a collection of free and equal individuals subject to the universal authority of the law. The debate of August 4, 1789, held at night, was in fact associated with a very powerful feeling in all the deputies that they were witnessing a twilight and a dawn. But even this classical simile cannot do full justice to the emotions of the participants in this celebrated session, who for a few hours felt as though they were divine mechanics helping to bring about this incredible spectacle. This twilight and this dawn were their work. (107)

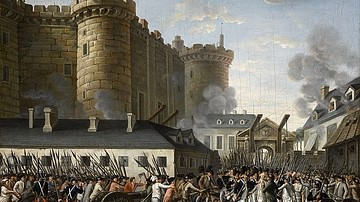

The twilight Furet refers to, namely the dismantling of the vestiges of feudalism in favor of a new body politic, had not been on the agenda of the National Constituent Assembly prior to 4 August. Instead, it was an almost impromptu decision, a reaction to the wave of panic and unrest that swept the countryside during the last weeks of July, in the wake of the Storming of the Bastille. The peasantry, already on edge thanks to half a decade of terrible harvests, had begun to circulate rumors about a plot by the nobility to starve them back into submission following the success of the Third Estate and the creation of the National Constituent Assembly. This conspiracy theory appeared to be further evidenced by the flight of noble emigres from the kingdom following the fall of the Bastille; it was only a matter of time, the reasoning went, before they would return at the heads of foreign armies to reassert their dominance by force.

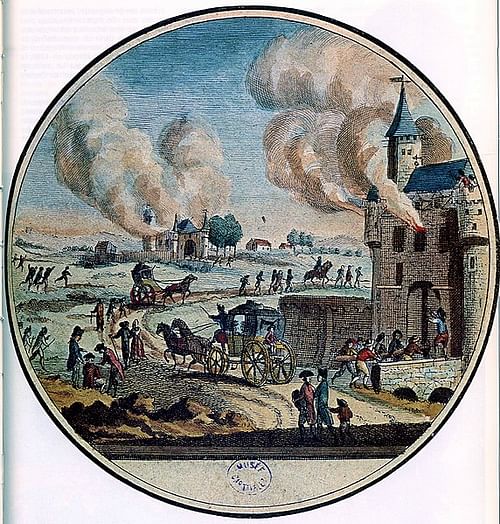

These rumors, aided by the breakdown in reliable communication due to the revolutionary excitement in Paris, caused groups of peasants to arm themselves and band together for their own defense. In an event referred to by historians as the Great Fear, some of these peasants attacked chateaux belonging to seigneurial lords. They burnt feudal records, including the registers in which lords recorded their various manorial dues, while also accosting the lords themselves, forcing them to renounce their feudal privileges. In an abrupt fashion, peasant uprisings broke out in the territories of Hainault, Alsace, Burgundy, and Franche-Comté, all within roughly three weeks. If nothing was done, it appeared the unrest would soon engulf even more of the kingdom.

The National Assembly had been preoccupied with debating the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, and its relation to the forthcoming constitution, when it was forced to change course to deal with the insurrections. The Assembly's first reaction was one of embarrassment, seeing as the uprisings had occurred despite the efforts of their newly created bourgeois citizen militias. On the night of 3 August, it was announced that "letters from all the provinces make it appear that properties of all kinds have fallen prey to the most criminal looting. Everywhere, chateaux are burned, convents destroyed, farms abandoned to pillage" (Furet, 108). While the Assembly acknowledged it had to act, suppression of the uprisings by use of arms was ruled out, as doing so would return legitimacy and authority to royal soldiers (despite some of the uprisings having already been put down by soldiers). Instead, a bill was drawn up, to be discussed the following night, that would reaffirm the "sacred value" of all forms of property and dues, while also developing a program of poor relief.

These were not the actions of an Assembly that intended to abolish feudalism. Indeed, many of the deputies may have seen little reason to do so; outside of pockets of territory such as Burgundy or Franche-Comté where feudalism still thrived, the seigneurial regime had long been in decline. Although France was still largely agricultural, a modernizing Europe allowed the nobility quicker paths to wealth than manorialism. Now having to compete with the rising bourgeois class for influence and power, some nobles began to turn towards investments in industry or land development. Still, traces of feudalism such as the corvée, a practice of unpaid and forced labor, were prevalent in regions where traditional manorialism was dying out.

Some deputies saw it as the Assembly's patriotic duty to rid the country of feudalism in all its various forms once and for all. The idea most likely sprouted during a meeting of the Breton Club, whose members met in secret after the conclusion of the session on 3 August to discuss the total destruction of all privileges belonging to any social classes, provinces, cities, or corporations. The precursor to the infamous Jacobin Club, the Breton Club had been founded by a group of anti-royalist delegates from Brittany, who met before every Assembly session to formulate a concerted strategy. By July, the club's membership was comprised of over 200 deputies. When the Assembly reconvened on the night of 4 August to discuss issues of property and the peasant insurrection, the members of the Breton Club were prepared to push their own agenda.

The Night of 4 August

Upon the opening of the session at 8 pm on 4 August, the discussion of the property bill was quickly derailed. Notably, the man who first stood up to condemn the privileges of the upper classes was Louis-Marie, vicomte de Noailles, himself an aristocrat descended from one of the most illustrious noble families in France. Noailles began his speech by acknowledging that while the rebellious peasants were indeed criminals, their crimes were justified due to the oppressive nature of their seigneurial lords, and they should therefore be excused.

He argued that the National Assembly was already at a crossroads in its young existence, stating that the kingdom floated between "the complete destruction of society and a government which would be admired and followed throughout Europe" (Schama, 438). The Assembly needed to prove its claims that it stood for the people, which could only be accomplished by officially abolishing systems of personal servitude, such as the corvée, and by allowing citizens to pay formal taxes only according to their means.

Finishing his speech, Noailles was immediately seconded by the Duc d’Aiguillon, one of the most heavily landed men in France. Aiguillon went even further than Noailles, arguing that the Assembly could only prove its commitment to human rights by removing the remnants of the "feudal barbarism" under which the people continued to suffer (Schama, 438). Following the passionate orations of these two prominent men, other nobles began shouting over one another, eager to prove their patriotism by discarding their privileges.

The ideas being thrown out by the excited deputies became increasingly radical. One deputy agreed to the full elimination of feudalism, speaking to humiliating titles that "required men to be tied to the plow like draft animals" (Schama, 438). Not long after, someone else proposed the abolition of tithes, much to the dismay of the assembled clergy. Perhaps in retaliation, the Bishop of Chartres then suggested ending the nobles' exclusive rights to game, arguing that any peasant should have the right to kill animals interfering with their crops. Other deputies spoke of the need for equality in criminal sentencing, and the end to all tax exemptions enjoyed by the nobility.

It was, as noted by Charles-Élie de Ferrières, "a moment of patriotic drunkenness" (Schama, 439). Before long, deputies were weeping, embracing one another, and singing patriotic songs. Naturally, not everyone present at the session approved of the direction the conversation was going. The Marquis de Lally-Tollendal was clearly disturbed, as he passed a note to his friend the Duc de Liancourt, who was presiding over the session, that read, "they are not in their right minds. Adjourn the session" (Schama, 439). When Liancourt refused to do so, Lally-Tollendal rose to his feet and attempted to do his best to salvage the situation. He reminded his fellow deputies to not forget the king, at whose invitation they had gathered in Versailles and who should therefore be proclaimed the "Restorer of French Liberty."

No bill regarding property and personal safety was discussed that night. Instead, 19 articles were drafted regarding the abolition of feudalism before the session finally ended at 2 am. As news of this development spread to the streets of Paris, widespread celebrations broke out. The Archbishop of Paris proposed a Te Deum to honor the event, while others wanted a national feast to be held on 4 August of every year.

Still, discussions were not yet concluded. It would take another week for the Assembly to finish debating the specifics of central issues, particularly regarding the matter of tithes. It was eventually decided that tithes would be abolished without indemnity, although the Church would still be allowed to collect them until the Assembly could work out an alternative. On Tuesday, 11 August, the final text was formally codified, with its opening sentence resounding across all corners of France: "The National Assembly entirely destroys the feudal regime" (Furet, 110).

The Articles

Of the 19 articles that made up the August Decrees, the most significant are summarized below:

- Article 1: The feudal system is entirely abolished. All feudal rights and dues, as well as personal servitude, are abolished with no compensation. All other kinds of dues are redeemable; the price and method of buying them back are determined by the National Assembly.

- Article 2: The exclusive right to fuies [allowing birds to graze] and dovecotes is abolished. Pigeons will be locked up during times determined by the communities.

- Article 3: Exclusive hunting rights are also abolished. Any landowner retains the right to kill any prey, but only on the land he owns. The king's hunting grounds, however, shall be preserved.

- Article 4: All seigneurial justices are abolished without compensation, although the offices will continue their duties until the National Assembly decides on a new judicial order.

- Article 5: All kinds of tithes are abolished without indemnity, pending notice of other means to subsidize the Church.

- Article 7: The practice of selling public offices is outlawed, and the principle of a feeless administration of justice affirmed.

- Articles 9-10: All special privileges are abolished, and every citizen must pay the same taxes on everything.

- Article 11: Any citizen, no matter their origins, can hold any military, civilian, or ecclesiastical job.

- Article 17: King Louis XVI is proclaimed the Restorer of French Liberty.

The King Responds

The passage of the August Decrees was the first test of King Louis XVI's new role as a patriot king. Upon backing down following the fall of the Bastille, the king had been forced to acknowledge the authority of the National Assembly by accepting their appointments of Jean Sylvain Bailly and the Marquis de Lafayette as mayor of Paris and commander of the National Guard, respectively. He had accepted a revolutionary cockade from Bailly before a crowd of citizens, many of whom interpreted the occasion as the king reconciling himself with the Revolution.

Of course, it was not as straightforward as all that. The king was of two opinions regarding the publication of the August Decrees. While he wrote in a letter to the Archbishop of Arles of his satisfaction with the Assembly's efforts toward class reconciliation, he could not bring himself to agree with the destruction of class privileges. "I will never consent," he wrote, "to the despoliation of my clergy and my nobility…I will never give my sanction to the decrees that despoil them, for then the French people will one day accuse me of injustice or weakness" (Schama, 442).

True to his word, Louis refused to sanction the decrees for weeks. On 18 September, he submitted his official remarks to the Assembly, drawn up by his recently reinstated minister Jacques Necker. In these remarks, the king assented to the principle of redeeming seigneurial rights but protested the list of rights that the Assembly had abolished without compensation. The king's refusal to wholeheartedly support the decrees remained a point of tension throughout the waning summer months of 1789. He did not give in until October when the Women's March on Versailles forcibly relocated the royal family to Paris and compelled him to consent to the decrees.

Aftermath & Significance

The August Decrees were a monumental step towards the dismantling of France's oppressive Ancien Régime. Within the span of a single night, burdensome tithes, outdated feudal dues, and the privileges of the upper orders were all done away with; or at least, that was how it looked on paper. In reality, things were quite messy as the Assembly attempted to clarify exactly what it had meant in its excited fervor that August night.

This naturally led to some confusion and misunderstanding. Much of the peasantry believed that the decrees were to take effect immediately, ignoring the caveats that many of the dues still had to be paid until a new system could be implemented. Many peasants resisted paying what they owed and became increasingly hostile toward taxation, which did not help France's already dire financial crisis. In fact, it was not until 1793, five years after the passage of the decrees, that all seigneurial dues were finally ended without indemnity.

Many in the upper orders were none too happy about the discarding of their valued privileges. Outraged nobles wondered how an Assembly, which had gathered ostensibly to vote on taxation issues, had accumulated enough authority to entirely destroy the feudal regime. The Church, too, protested the abolition of their tithes. This was the subject of the fiercest debate in the days between 4 August and the formalizing of the decrees a week later. It was during these debates that the idea was first put forth that Church property belonged to the state, which would eventually lead to the confiscation of Church lands. The tithe was not abolished in practice until 1 January 1791, but the passage of the decrees was the beginning of the animosity between the Church and the Revolution that would lead to bitter and bloody conflict.

In November 1789, France's 13 parlements, or high judicial courts, were suspended, as stipulated in the decrees. They were completely abolished the following year. This was a major fall from grace for an institution that had been hailed as the shield of the people against royal tyranny only a year earlier during the Revolt of the Parlements. Yet, it was also another brick taken from the walls that made up the Ancien Régime, as the parlements had consistently served as a tool for the nobility to gain power.

The legacy of the August Decrees has been analyzed by historians in the centuries following their creation. Some have been less than impressed by their outcome, arguing that the decrees did nothing but acknowledge the emerging status quo. After all, feudalism was already dying out in France, so the noble deputies were not truly sacrificing much. To counter these views, it should be noted what a significant achievement the complete abolition of feudalism was. Even if the system was dying out anyway and would not be fully abolished until 1793, the act struck down a foundational element of the Ancien Régime and allowed for the construction of a new body politic. The August Decrees paved the way for the passage of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a watershed document in the history of human rights. To claim that many of the nobles did not risk much financially could be true, but to claim that they were acting purely out of selfishness would be unfair. Nobles like Noailles, who had served under his brother-in-law Lafayette in the American Revolutionary War, were truly passionate for freedom and, likely, did feel as if they were carrying out their patriotic duties.

The August Decrees were a significant development in the French Revolution and arguably one of the Revolution's most important and lasting achievements. While many edicts passed by the multiple successive governments of the Revolution were as fleeting as those governments themselves, the August Decrees endured, going so far as to influence the future Civil Code, more commonly referred to as the Napoleonic Code, passed in 1804. The August Decrees embodied ideals of liberty, equality before the law, and property, which were fundamental to the Age of Enlightenment and significant building blocks of western democracies.