The Avesta is the scripture of Zoroastrianism which developed from an oral tradition founded by the prophet Zoroaster (Zarathustra, Zartosht) sometime between c. 1500-1000 BCE. The title is generally accepted as meaning “praise”, though this interpretation is not universally agreed upon.

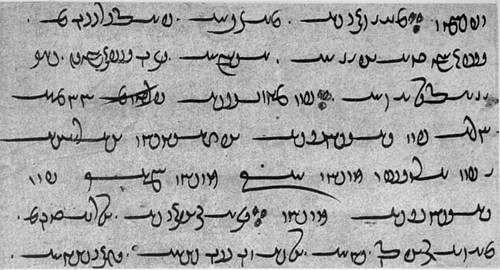

The original prayers and hymns were composed in a now-extinct language known as Avestan (which takes its name from the work) that was only preserved orally until the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE), which committed it to writing by essentially inventing an alphabet to convey Avestan based on Aramaic script. It is usually divided into the following sections:

- Yasna-Gathas

- Vispered

- Yashts

- Vendidad

- Minor Texts

- Fragments

Zoroastrian tradition holds that the original work of 21 books (known as Nasts) was revealed by Ahura Mazda, the One True God, to Zoroaster who recited them to his benefactor King Vishtaspa who had them inscribed on sheets of gold. This original work was then memorized, recited at services (yasna), and passed down through the generations until committed to writing by the Sassanians, at which time it was accompanied by commentaries and other works such as the Zend (also given as Zand) and, later, the Denkard, and the Bundahisn.

The work, as recognized today, contains the original compositions attributed to Zoroaster as well as ecclesiastical laws, commentaries, customs, and beliefs which developed later after Zoroastrianism was accepted and became a widespread belief. The core of the Avesta is thought to have been recognized and recited by Zoroastrian Persians from the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) through the Sassanian Empire which fell to the invading Muslim Arabs in 651 CE.

Afterwards, Zoroastrianism was suppressed and only preserved by the Parsees – Persian Zoroastrians who fled to India – and Iranians who managed to keep the faith alive in their native country. In the present day, the Parsees are considered the primary custodians of the Avestan tradition although Zoroastrianism is practiced by people around the world.

Zoroaster & Early Development

The Early Iranian Religion was polytheistic with Ahura Mazda as king of the gods. These gods, and attendant spirits, were forces for good and stood in opposition to the discordant spirit Angra Mainyu and his legions of evil. There was a priesthood, which attended to the gods, and services conducted, but what form these rituals took is unknown.

Roughly between c. 1500-1000 BCE, one of these priests, Zoroaster, received a vision from Ahura Mazda through a being of light who appeared to him on a riverbank. The entity identified itself as Vohu Manah (“good purpose”) and revealed to him that there was actually only one god – Ahura Mazda – and Zoroaster's responsibility was to preach this truth.

Zoroaster's early efforts were not appreciated by the priesthood – nor anyone else – and after his life was threatened he left his home region, eventually arriving at the court of King Vishtaspa. Although originally imprisoned for his vision, Zoroaster won the king's admiration by healing his favorite horse, and Vishtaspa became his first notable convert; his kingdom then followed suit, and the religion spread from there.

The faith was based on Ahura Mazda's revealed truth of a single god who was all-good, all-powerful, and completely loving. This god only required acknowledgment and that human beings express this through good thoughts, good words, and good deeds, which would lead to virtuous lives. Virtuous people would honor truth (asha) and repudiate lies (druj) and, in doing so, fight against the forces of Angra Mainyu and preserve order.

The earliest section of the Avesta is the Gathas – hymns to Ahura Mazda which are thought to have been composed by Zoroaster. They address the god directly and ask for guidance in living the life he expects from adherents. According to legend, as noted, these hymns and other works were written down under Vishtaspa, but there is no actual evidence for the golden sheets of Zoroastrian scripture nor for any other written Zoroastrian works prior to the Sassanian Empire.

Achaemenid, Parthian, & Sassanian Development

The religion was adopted by the Achaemenid Empire, probably during the reign of Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE). The founder, Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE), references Ahura Mazda, but such inscriptions could be alluding to the earlier vision of the polytheistic faith. Allegedly, the Achaemenids wrote down a version of the Avesta which was destroyed by Alexander the Great's conquest and the burning of Persepolis in 330 BCE. Modern-day scholars reject this claim, however, noting that there is nothing in the extant work which suggests an earlier Achaemenid version.

The Achaemenid Empire was succeeded by the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire (312-63 BCE) during which time Zoroastrianism continued to be practiced by the people but not the Greek upper class. The Seleucids were succeeded by the Parthian Empire (247 BCE-224 CE) whose upper class did embrace Zoroastrianism, and early scholars of the religion claimed that a version of the Avesta was written at this time. This version was allegedly based on the texts supposedly lost at the end of the Achaemenid Empire, but, again, there is no evidence for this, and most modern-day scholars reject the claim or, at least, see nothing in the extant work which would make a Parthian version relevant to its development.

The Sassanians are the first historically attested Persian empire to have committed the work to writing; inscriptions, as well as the extant text, make this quite clear. The founder of the Sassanian Empire, Ardashir I (r. 224-240 CE), brought Zoroastrian priests to his court to recite the sacred verses so they could be written down and this policy was continued by his son Shapur I (r. 240-270 CE). The work does not seem to have been actually completed, however, until the reign of Shapur II (309-379 CE) and was not finalized until that of Kosrau I (531-579 CE).

Priests recited the text in its original Avestan, and this was then rendered in a script invented for this sole purpose in order to preserve the precise sound and sense of the Avestan words. The script was based on Aramaic but departs from that language in order to preserve the lost Avestan. This method was initiated under Shapur II and continued by his successors.

The Avesta

The most important section of the Avesta is the Gathas. These are personal praise songs comprised of prayer-petition and worship-adoration and, on their own, provide little by way of instruction in how one is to walk the Zoroastrian path in one's daily life. It is thought that Zoroaster must have taught his disciples how to conduct themselves in plain, direct speech, and some of this tradition could be preserved in commentary such as the Zend. However that may be, it is because of the ambiguity of the Gathas that works such as the Vendidad, Minor Texts, and Zend are necessary.

Yasna-Gatha

The Yasna-Gathas are 17 such hymns divided into five groups based on meter:

- Ahunavaiti Gatha

- Ushtavaiti Gatha

- Spentamainyush Gatha

- Vohukshathra Gatha

- Vahishtoishti Gatha

The yasna (devotion) is the Zoroastrian religious service but also alludes to the hymns which encourage devotion while the Gatha is the separate grouping of those hymns. Their purpose is to elevate the mind toward enlightenment by focusing it on the grandeur of Ahura Mazda. Yasna 28 from the Ahunavaiti Gatha is a good example of the overall theme and focus of these works:

1. With outspread hands in petition for that help, O Mazda, I will pray for the works of the holy spirit, O thou the Right, whereby I may please the will of Good Thought and the Ox-Soul.

2. I who would serve you, O Mazda Ahura and Vohu Mano, do ye give through Asha the blessings of both worlds, the bodily and that of the Spirit, which set the faithful in felicity.

3. I who would praise ye as never before, Right and Good Thought and Mazda Ahura, and those for whom Piety makes an imperishable Dominion to grow; come ye to me help at my call.

4. I who have set my heart on watching over the soul, in union with Good Thought, and as knowing the rewards of Mazda Ahura for our works, will, while I have power and strength, teach men to seek after Right.

5. O Asha, shall I see thee and Good Thought, as one that knows? (Shall I see) the throne of the mightiest Ahura and the following of Mazda? Through this word (of promise) on our tongue will we turn the robber horde unto the Greatest.

6. Come thou with Good Thought, give through Asha, O Mazda, as the gift to Zarathushtra, according to thy sure words, long enduring mighty help, and to us, O Ahura, whereby we may overcome the enmity of our foes.

7. Grant, O thou Asha, the reward, the blessing of Good Thought; O Piety, give our desire to Vishtaspa and to me; O thou Mazda and King, grant that your Prophet may command a hearing.

8. The best I ask of Thee, O Best, Ahura (Lord) of one will with the Best Asha, desiring (it) for the hero Frashaostra and for those (others) to whom thou wilt give (it), (the best gift) of Good Mind through all time.

9. With these bounties, O Ahura, may we never provoke your wrath, O Mazda and Right and Best Thought, we who have been eager in bringing you songs of praise. Ye are they that are the mightiest to advance desire and the Dominion of Blessings.

10. The wise whom thou knowest as worthy, for their right (doing) and their good thought, for them do thou fulfill their longing for attainment. For I know words of prayer are effective with Ye, which tend to a good object.

11. I would thereby preserve Right and Good Thought for evermore, that I may instruct, do thou teach me, O Mazda Ahura, from thy spirit by thy mouth how it will be with the First Life.

(Avesta.org)

In this hymn – as in all the others – the importance of the pursuit of truth (asha) and wisdom (mazda) is emphasized as well as the transcendent nature of Ahura Mazda (Lord of Wisdom) and the necessity of resisting evil to maintain order.

Visperad

The Visperad comprises 23 prayers which serve as a supplement to the yasnas but is also the name of the ceremony in which these prayers are recited (in ancient times, conducted between the rising of the sun and noon). The prayers of the Visperad are never recited independently of the yasnas as they serve to expand upon and develop the hymns' concepts.

Yashts

The Yashts are 21 hymns addressed to divine entities and sacred elements such as water and fire. When Zoroaster reformed the earlier religion, he kept many of the most popular gods – such as Anahita (goddess of water, fertility, health, and wisdom) and Mithra (god of the rising sun, contracts, and covenants), only now these were no longer regarded as deities but as divine emanations of Ahura Mazda. One could still, therefore, pray to Anahita for help in conceiving a child but in the knowledge one was actually praying to Ahura Mazda; Anahita would only be the vehicle through which the Supreme Deity answered the prayer (very like the Catholic conception of praying to saints). The Yashts are these kinds of supplications in the form of hymns which also give thanks for answered prayers.

Vendidad

The Vendidad is a collection of 22 sections (Fargards) which make up an ecclesiastical code and includes myths, prayers, observances, rituals, and instruction on subjects ranging from personal hygiene to social customs (acceptable and unacceptable behavior), defense against evil demons, care for the dead and funerary rituals (including the importance of dogs in driving off evil spirits after a death), respect for others, charity, and care for animals, among many other topics. The different Fargards address specific answers to questions on how one is to be a Zoroastrian, what that means as far as a daily walk of faith, and how one is to respond to various threats, actions, blessings, and other circumstances.

Some Zoroastrians in the present day reject the Vendidad as superfluous while others accept its validity. Scholars, however, generally agree that the Fargards are some of the oldest Zoroastrian texts, the content dating back to around the 8th century BCE. The early myth of the creation of the world, the story of King Yima and the salvation of the earth (an early precursor to the later biblical tale of Noah and his Ark), and the importance of caring for the earth – all considered ancient tales – are included in the Vendidad and make up the first three Fargards.

Minor Texts

The so-called Minor Texts are prayers and invocations of various deities for assistance. As with Anahita and Mithra and other former-gods, these deities are regarded as emanations of Ahura Mazda. They are particular energies more conducive to answering a certain type of prayer than others. The Minor Texts are:

- Siroza – Invocations of deities in times of need

- Nyayeshes – Prayers to divine elements of fire, water, and to the sun and moon

- Gahs – Invocations of and prayers to the Five Deities of the Day

- Afrinagans – Blessings for the Dead and for the Seasons

Fragments

The fragments are incomplete texts or those which do not fit with any other section. Although often overlooked, the fragments are not inconsequential and include information on pre-Zoroastrian deities and important theological subjects such as the end of the world and redemption.

Loss & Recovery

In 651 CE, the Sassanian Empire fell to the Muslim Arabs and Zoroastrianism was suppressed. People either converted to Islam, continued the faith in secret, or fled the region (the Parsees who took the religion to India where it continues to flourish). The Muslims burned the Zoroastrian libraries and either destroyed the fire temples or turned them into mosques. Scholars regularly point to this period as one of incalculable loss of Zoroastrian texts and lore, including copies of the Avesta. The Parsees took the Avesta with them to India (Gujarat) at some point between the 8th and 10th centuries CE. Zoroastrian beliefs outside of India, for the most part, were only known through commentary by Greek, Christian, and Muslim writers. The actual Avesta was thought to have been lost in the Muslim conquest of the 7th century CE.

It was not until 1723 CE, when a merchant traveling in India brought back part of an Avestan manuscript to Britain, that Europeans became aware the book still existed, at least in part. This manuscript was placed in the Bodleian Library of Oxford University where, in 1755 CE, it came to the attention of the young French scholar Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron (l. 1731-1805 CE), later the greatest Indologist of his age. Anquetil-Duperron, embarking on an epic journey through India to recover the Avesta, returned to France with over 180 Avestan manuscripts in 1762 CE and began to translate them; all Western Avestan scholarship develops from Anquetil-Duperron's efforts.

Legacy

The Avesta is a completely original vision of its age, conceiving of a single, all-powerful, creative deity with a personal interest in the lives – and morality – of human beings. Its principles informed the policies of the greatest empires of the ancient East and its theology would influence the later monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Zoroastrianism is the first monotheistic religion to introduce concepts such as judgment after death, heaven and hell, a messiah, an End Time, resurrection of the dead, and a new world after the old is redeemed, among others; all concepts developed by the later monotheistic faiths.

These belief systems would have been informed by Zoroastrian thought as the concepts were shared through trade and travel between c. 1000 BCE and 224 CE when the Sassanians wrote the work down. Even if it had never exerted any influence on these later faiths, however, the Avesta would still be a powerful work in its own right as it provides a vision of a completely loving deity, generous and just, who only wants his creation to be the best it can possibly be in every respect.