The religion of the Aztec civilization which flourished in ancient Mesoamerica (1345-1521 CE) has gained an infamous reputation for bloodthirsty human sacrifice with lurid tales of the beating heart being ripped from the still-conscious victim, decapitation, skinning and dismemberment. All of these things did happen but it is important to remember that for the Aztecs the act of sacrifice - of which human sacrifice was only a part - was a strictly ritualised process which gave the highest possible honour to the gods and was regarded as a necessity to ensure mankind's continued prosperity.

Origins & Purpose

The Aztecs were not the first civilization in Mesoamerica to practise human sacrifice as probably it was the Olmec civilization (1200-300 BCE) which first began such rituals atop their sacred pyramids. Other civilizations such as the Maya and Toltecs continued the practice. The Aztecs did, however, take sacrifice to an unprecedented scale, although that scale was undoubtedly exaggerated by early chroniclers during the Spanish Conquest, probably to vindicate the Spaniards own brutal treatment of the indigenous peoples. Nevertheless, it is thought that hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of victims were sacrificed each year at the great Aztec religious sites and it cannot be denied that there would also have been a useful secondary effect of intimidation on visiting ambassadors and the populace in general.

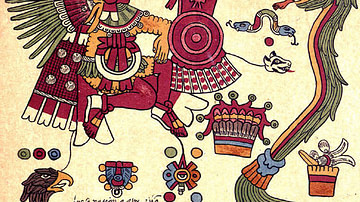

In Mesoamerican culture human sacrifices were viewed as a repayment for the sacrifices the gods had themselves made in creating the world and the sun. This idea of repayment was especially true regarding the myth of the reptilian monster Cipactli (or Tlaltecuhtli). The great gods Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca ripped the creature into pieces to create the earth and sky and all other things such as mountains, rivers and springs came from her various body parts. To console the spirit of Cipactli the gods promised her human hearts and blood in appeasement. From another point of view sacrifices were a compensation to the gods for the crime which brought about mankind in Aztec mythology. In the story Ehecatl-Quetzalcóatl stole bones from the Underworld and with them made the first humans so that sacrifices were a necessary apology to the gods.

Gods then were 'fed' and 'nourished' with the sacrificed blood and flesh which ensured the continued balance and prosperity of Aztec society. In Nahuatl the word for sacrifice is vemana which derives from ventli (offering) and mana 'to spread out' representing the belief that sacrifices helped in the cycle of growth and death in food, life and energy. Accordingly, meat was burnt or blood poured over the statues of deities so that the gods might partake of it directly. Perhaps the quintessential example of 'feeding' the gods were the ceremonies to ensure Tezcatlipoca, the sun god, was well-nourished so that he had the strength to raise the sun each morning.

Non-Human Sacrifices

Blood-letting and self-harm - for example, from the ears and legs using bone or maguey spines - and the burning of blood-soaked paper strips were a common form of sacrifice, as was the burning of tobacco and incense. Other types of sacrifice included the offering of other living creatures such as, deer, butterflies and snakes. In a certain sense offerings were given in sacrifice, precious objects which were willingly handed over for the gods to enjoy. In this category were foodstuffs and objects of precious metals, jade and shells which could be ritually buried. One of the most interesting such offerings was the dough images of gods (tzoalli). These were made from ground amaranth mixed with human blood and honey, with the effigy being burnt or eaten after the ritual.

Preparing the Victims

With human sacrifices, the sacrificial victims were most often selected from captive warriors. Indeed, warfare was often conducted for the sole purpose of furnishing candidates for sacrifice. This was the so-called 'flowery war' (xochiyaoyotl) where indecisive engagements were the result of the Aztecs being satisfied with taking only sufficient captives for sacrifice and where the eastern Tlaxcala state was a favourite hunting-ground. Those who had fought the most bravely or were the most handsome were considered the best candidates for sacrifice and more likely to please the gods. Indeed, human sacrifice was particularly reserved for those victims most worthy and was considered a high honour, a direct communion with a god.

Another source of sacrificial victims was the ritual ball-games where the losing captain or even the entire team paid the ultimate price for defeat. Children too could be sacrificed, in particular, to honour the rain god Tlaloc in ceremonies held on sacred mountains. It was believed that the very tears of the child victims would propitiate rain. Slaves were another social group from which sacrificial victims were chosen, they could accompany their ruler in death or be given in offering by tradesmen to ensure prosperity in business.

Ritual & Death

Conducted at specially dedicated temples on the top of large pyramids such as at Tenochtitlan, Texcoco and Tlacopan, sacrifices were most often carried out by stretching the victim over a special stone, cutting open the chest and removing the heart using an obsidian or flint knife. The heart was then placed in a stone vessel (cuauhxicalli) or in a chacmool (a stone figure carved with a recipient on their midriff) and burnt in offering to the god being sacrificed to. Alternatively, the victim could be decapitated and or dismembered. M.D.Coe suggests that this method was typically reserved for female victims who impersonated gods such as Chalchiuhtlicue but images recorded by the Spanish in various Codex do show decapitated bodies being flung down the steps of pyramids. Those sacrificed to Xipe Totec were also skinned, most probably in imitation of seeds shedding their husks.

Victims could also be sacrificed in a more elaborate process where a single victim was made to fight a gladiatorial contest against a squad of hand-picked warriors. Naturally, the victim had no possibility to survive this ordeal or even inflict any injury on his opponents as not only was he tied to a stone platform (temalacatl) but his weapon was usually a feathered club while his opponents had vicious razor-sharp obsidian swords (macuauhuitl). In another method, victims could be tied to a frame and shot with arrows or darts and in perhaps the worst method of all, the victim was repeatedly thrown into a fire and then had his heart removed.

After the sacrifice, the heads of victims could be displayed in racks (tzompantli), depictions of which survive in stone architectural decoration, notably at Tenochtitlán. The flesh of those sacrificed was also, on occasion, eaten by the priests conducting the sacrifice and by members of the ruling elite or warriors who had themselves captured the victims.