The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress was a four-engined heavy bomber plane used by the air forces of the United States and Britain during the Second World War (1939-45). The B-17 had unusually heavy defensive armament, 13 machine guns in total in some models. B-17s were involved in strategic bombing operations in Europe, the Pacific, and other theatres of the war.

Design & Development

In August 1935, the US Army Air Corps organised an evaluation of various prototypes from different aircraft manufacturers at Wright Field, Ohio. The Boeing Aircraft Company showed off its four-engined Model 299, and, after extensive trials, the aircraft impressed sufficiently to gain the green light for production of 13 examples of the new bomber that would become known as the Boeing 17. These planes were first flown in December 1936.

The B-17 was first in operation with the US Army Air Force (USAAF) in 1937 and so became the first four-engined monoplane bomber with an all-metal bodywork to see service in any country. The first B-17 squadron was based at Langley Field, Virginia. More aircraft were ordered, but this was a period when the US Air Force was still officially part of the army, which was battling for resources with the US Navy. For this reason, there were fewer than 30 operational B-17 bombers when the Second World War broke out in Europe in September 1939. Fortunately for the Allies, not much happened in the war until March 1940, and by then, the US could put into the air an additional 39 B-17s. This was still a woefully inadequate number, and more bombers were ordered and produced through the summer of 1940.

The B-17 allowed bombing campaigns to be conducted from a high altitude, even though at this stage of the war, it was not clear if the U.S. would use them in anger. Early B-17 types had only five small machine guns fitted, which were later increased to seven. With the U.S. continuing to pursue an isolationist policy, President Franklin D. Roosevelt (l. 1882-1945) instead turned to supplying Britain with arms. 20 B-17s were supplied to the Royal Air Force (RAF) in the first months of 1941. These bombers became the first B-17s to bomb a target when they were deployed over Wilhelmshaven on the German coast on 8 July 1941. More operations followed, but these demonstrated that the plane's capability of flying at a high altitude was not a sufficient defence against enemy fighter planes. More and heavier guns were needed, and in the meantime, the B-17s were withdrawn from RAF service.

The aircraft continued to go through several design improvements. The B-17, from version E onwards, had heavier and more guns, self-sealing fuel tanks that could better withstand enemy fire, a larger tail to help stability, and extra armour plating to protect the crews. The B-17F had even bigger fuel tanks and strengthened landing gear so that more bombs could be carried. The most-produced model during WWII was the B-17G, which had two machine guns added to the chin. Built from 1943 onwards by Boeing, Douglas, and Lockheed Vega factories, 8,680 B-17Gs rolled off the production line. In all, 12,731 B-17 of all marks were built.

The Crew

The B-17 crew was composed of ten men: the pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier, engineer and a radio operator (both of whom doubled as gunners on the upper fuselage), and four more gunners (in the belly, port and starboard sides, and tail). The pilots, the navigator, and the bombardier were officers. All crew were volunteers for the bombing missions. Due to the risks involved, USAAF flyers were given a maximum of 25 missions per combat tour, later extended to 35.

The bombardier used the latest technology available, the Norden bombsight, but he still required clear visibility of the target, a rare occurrence given that the air above targets was frequently obscured by a combination of smoke from fires below, anti-aircraft flak, and clouds. For completely obscured targets, the H2S ground-search radar system was used (called H2X in the USAAF), although this could be jammed by signals sent out from enemy planes.

Specifications

The B-17 was powered by four turbocharged Wright Cyclone engines, capable of 1,200 hp (895 kW) each. The aircraft measured 74 ft 4 in (22.66 m) in length and had a wingspan of 103 ft 9 in (31.62 m). The maximum speed was 287 mph (462 km/h) with a service ceiling of 35,600 ft (10,850 m). Flying above 10,000 ft (3,048 m) required the crew to wear oxygen masks. The B-17's maximum range was around 2,000 miles (3,220 km).

The aircraft earned its name as a "fortress" because it was first envisaged as a moving fortress capable of defending the coastline of the United States. During the war, the name seemed particularly appropriate, given the aircraft was bristling with machine guns. These guns were for defence against enemy fighter planes like the Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero and the German Messerschmitt Bf 109. The B-17 had five main gun turrets and several single-gun ports. There were two machine guns in the nose and two in the bombardier's space just below. There were two guns in a turret above the pilots, one further down the spine of the plane, two under the plane just behind the wings, one on each side of the fuselage towards the rear, and two in the tail. All 13 of the machine guns of the B-17G were calibre 0.50 inches (12.7 mm) capable of firing at a rate of 800 rounds per minute.

There was a price to pay for having such a large crew and so many machine guns, and this was in the limitation imposed on the weight of bombs the aircraft could carry. The B-17 was capable of carrying a bomb load of 6,000 lb (2,722 kg), an impressive amount but significantly less than the RAF's Lancaster bomber, which could carry a load of 14,000 lbs (6,350 kg) of multiple bombs or a single gigantic bomb of 22,000 lbs (10 tons). The Flying Fortress could be loaded with less fuel and so increase the bomb load to 17,600 lbs (7,983 kg), but this was only for short-range missions.

Operations

In 1941, four squadrons of B-17 bombers were sent to the Philippines where the USAAF had a major air base at Clark Field on Luzon Island. Unfortunately, the majority of the 35 B-17s were destroyed or badly damaged in a Japanese air strike on 8 December 1941, one day after the attack on Pearl Harbour, the US naval base in Hawaii. Other theatres of use included the Middle East. Primarily used as a bomber, the B-17 could be adapted for a range of specific purposes such as reconnaissance, air-sea rescue, cargo transport, personnel carriers, and training craft.

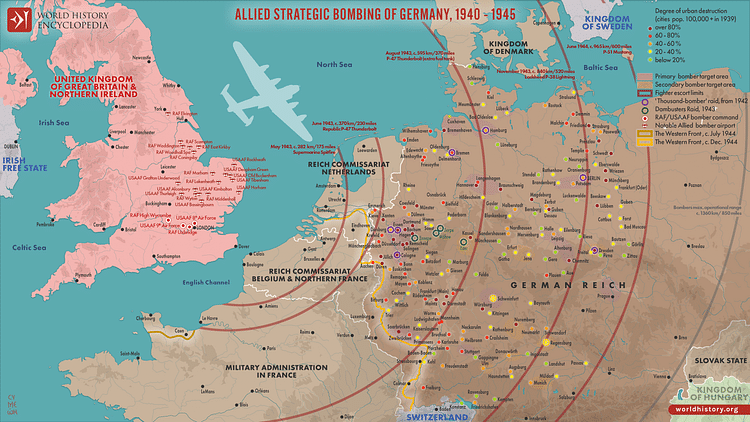

The B-17 was the USAAF's preferred strike bomber in Europe during WWII, although others were used in large numbers such as the B-24 Liberator (actually the most produced US aircraft of the war). These bombers were part of the US Eighth Air Force which flew from bases in Britain. The first B-17 bombers to fly US colours in Europe were part of the 97th Bombardment Group, which attacked Rouen in France on 17 August 1942 with fighter escort provided by RAF Supermarine Spitfires.

The Hollywood actor James Stewart (1908-1997), who flew several types of bomber in the war and who worked as an instructor for B-17 crews for a time, had this to say on the dangers of bombing raids over Europe:

The fighter, he was the bogeyman in this tremendous, vicious defence that they mounted. The flak, although it got much more serious in the latter part of the war, for some reason I always felt that the odds were better in your favour with flak. The fighter, though, had eyes and in a great many instances the fighter had a pretty competent pilot at the controls, and when he latched on to you, you were in trouble.

(Holmes, 428)

The RAF had found that daylight bombing resulted in too many planes being shot down by enemy fighters and anti-aircraft guns on the ground. Consequently, the RAF switched to night-time bombing when it was much more difficult to find and attack bomber planes. Unfortunately, this also meant that bombing accuracy was seriously reduced, which, in turn, led to a new strategy being adopted, which was to switch from targeting precise targets like factories to dropping bombs over a larger area but still hoping to hit the same factories. This strategy is known as area bombing, and it had the consequence that a great many civilians were killed in bombing raids.

When the USAAF joined the strategic bombing campaign in Europe, the attempt was made once again to conduct daylight raids on specific targets vital to Germany's war effort. The USAAF high command believed that they could avoid the heavy losses the German Luftwaffe had experienced over Britain and the RAF had experienced over Germany because the B-17 bomber was more heavily armed and because they would fly in a much tighter formation where machine gunners could protect their neighbours and hit approaching fighters with a barrage of fire. The typical USAAF bomber formation had been six planes forming a "W" with the leader in the centre and a little forward of the group. For a tighter formation, from September 1942, B-17s flew in groups of 18 in a zig-zag line about 2,300 ft (700 m) in length and around 480 ft (150 m) from front to rear. In addition, the line was stepped vertically so that half of the planes were flown 500 ft (152 m) higher than the second half of the line. The problem with the formation was that when it turned it inevitably left stragglers exposed to enemy fighters. A solution was to put three formations together and create a tight group of 54 bombers. The 54-plane wing measured around 2,200 yards (2,000 m) across and 880 yards (800 m) deep. As the war progressed, the 54-plane wing became even tighter but then had to be spread out again as German anti-aircraft fire intensified towards the end of the conflict.

To some degree, the tighter formations fared better, but the losses were still high. The German fighters soon learned that the weak spot of the B-17 was the nose, and so they attacked head-on and avoided all the other machine guns, which were mostly placed to fend off an attack from the rear. There were also significantly more losses from mid-air collisions due to the close proximity of the planes in their flying formation. Finally, as with all heavy bombers compared to much nimbler fighter planes, the slow-flying B-17s remained easy targets for the German fighters if they could get in amongst the formation and break it up. As the aviation historian R. Neillands states, "the hard-learned lesson that the bomber could not operate on its own in daylight over German-occupied territory had to be learned all over again – at a considerable cost in young American lives" (163). Many missions lost more than 10% of the aircraft sent in, a figure considered the absolute operational limit.

One B-17 pilot, Bruce Kilmer, remembered his first daylight mission, part of a group of B-17s sent to attack a factory in Antwerp in May 1943:

Our group put up a total of eighteen B-17s, and the USAAF had no fighter planes available at this time and we would be escorted by British Spitfires – little did we know that they barely had the range to cross the water. Nor were we mentally prepared for the number of yellow-nosed FW 190s and checkerboard Me 109s that seemed to be everywhere. The German pilots were very good and very daring, and at that time we thought the flak over the target was very bad – we had not yet been to Germany. Suddenly, when the bad guys started shooting at us flying was no longer fun. We lost two planes and twenty men that day – our first mission; 24 to go.

(Neillands, 211)

There was also the consequence that the tighter bomber formations did not allow for precise bombing and so the pattern bombing technique was adopted where all the formation's bombs were dropped at the same time. This was the reason why, as the war progressed, RAF night bombing, which deployed small but successive waves of bombers hitting a previously marked target, became more accurate than USAAF daylight bombing.

From March 1944, a new development radically shifted the balance in favour of the bombers, the arrival of the P-51 Mustang. The Mustang had a much longer range than the fighters previously available, and so the bomber squadrons could be escorted all the way to their target and be protected from enemy fighters. The escort meant that bombers did not need to fly in such tight formations; the looser version tended to have three squadrons of 12 planes fly in an arrow formation and then, even looser, four squadrons of nine bombers, all flying at a different altitude.

There is a common myth that the USAAF bombed specific military targets and the RAF bombed cities in WWII, but this was not so. Both air forces conducted both types of raids throughout the war. In addition, the technology was simply not available until 1944 for any bomber in any air force, Allied or Axis, to drop their loads with a high degree of accuracy. "Collateral damage" was unavoidable, even when a specific target was the objective since a wide area around it would be bombed, and so if the target was anywhere near housing, a large number of civilian casualties occurred. It is true that the RAF concentrated on night raids and the USAAF on day raids. This Combined Bomber Offensive meant that many German defences came under constant pressure. Sometimes specific targets were attacked in a night-day combination over several days such as Hamburg in Operation Gomorrah in July-August 1943.

Schweinfurt-Regensburg Raid

The B-17 Flying Fortress was involved in both area bombing and specifically identified targets. A famous example of the latter is the raid on the factories at Schweinfurt and Regensburg in Germany on 17 August 1943 and again on 14 October. At Schweinfurt, there were five factories producing ball bearings, a crucial component for all kinds of military machinery, while Regensburg had an important Messerschmitt aircraft plant. The plan was to make the attack in two closely timed bomber waves so that enemy fighters might not have time to refuel and rearm when the second wave reached the target. In all, 376 B-17s attacked Schweinfurt and Regensburg in August.

The combined raids were deemed a partial success in that enemy production was seriously affected, but the losses were high. Almost 150 bombers were lost overall, too high a loss rate to be sustained. 482 airmen were lost, of which more than 100 were killed in the August raid alone. Unfortunately for the Allies, Germany had reserves of ball bearings, which meant it could continue with supplies until the factories were repaired. However, the German Armaments Minister Albert Speer (1905-1981) noted:

Of course we were frightened that there will be other raids on Schweinfurt and really there were other raids but too late. If you would have repeated those raids shortly afterwards and wouldn't have given us time to rebuild then it would have been a disastrous result.

(Holmes, 431).

Dresden Raid

On 14 February 1945, 311 B-17 Flying Fortress bombers dropped their loads on Dresden, and this after the Royal Air Force had area-bombed the city the night before using 796 Lancasters. The B-17 bombers' aiming point was the train marshalling yards, but other parts of the city were, inevitably, struck. More Flying Fortresses returned to bomb Dresden on 15 February and 2 March. In the bombing of Dresden in 1945 around 30,000 civilians were killed. Lieutenant General Eaker, Commander of the Eighth Air Force, had this to say on the controversial Dresden bombing:

I don't agree there was overkill. There may have been in Dresden, but bear in mind we'd been asked by the Russians to destroy that great railroad complex because most of the German weapons and supplies and reinforcements going to the central section of the Eastern Front were going through there.

(Holmes, 440)

Legacy

One of the most famous aircraft of the Second World War, the Flying Fortress has gained iconic status as the greatest of bombers of the USAAF in the European campaign, bombing countless targets in Germany, Italy, and occupied Europe, as well as supporting the D-Day Normandy landings and the push across Western Europe. In the Pacific theatre of the war, the B-29 Superfortress dominated. This was a much larger and more sophisticated aircraft than the B-17 and one which could carry twice the bomb load. The B-29, very much the B-17's successor, dropped the atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Nagasaki and Hiroshima in August 1945.