The Bacchae is a Greek tragedy written by the playwright Euripides (c. 484-406 BCE) in 407 BCE, which portrays Pentheus as an impious king, for the ruler of Thebes has denied the worship of Dionysus within his city walls. For Pentheus, the god is a destroyer of social and moral values, and the former has returned from abroad only to have his conceptions of the god strengthened. He discovers that this false divinity has caused his women to abandon their domestic roles for the freedom of Mt. Cithaeron in order to worship Dionysus. Despite Pentheus' diligent efforts to maintain control over his people, city, and self, Dionysus proves to be an unstoppable force that the King of Thebes is not able to keep under lock and key.

Euripides

As with many individuals in antiquity, little is known about the life of Euripides (c. 484-406 BCE). It is speculated that the playwright was born in 484 BCE at Salamis, and he first performed at the Great Dionysia in 455 BCE. Distancing himself from public life, Euripides, unlike both Aeschylus and Sophocles, did not hold military or religious positions. Euripides wrote the Bacchae in 407 BCE, one year after he left Athens to spend the final two years of his life in Pella at the court of King Archelaus. According to William Arrowsmith in his introduction to the text, Euripides' son brought the Bacchae, along with the plays Iphigenia at Aulis and Alcmaeon at Corinth, back to Athens in order to be produced at the City Dionysia. Euripides' Bacchae is the only tragedy out of 18 surviving texts in which the Greek god Dionysus appears, the divinity whom the City Dionysia honors.

Characters

The Bacchae, like most Greek tragedies, employs a short list of characters:

- Dionysus

- the chorus comprised of maenads

- Cadmus, the former king of Thebes

- Tiresias, the blind seer

- Pentheus, the current king of Thebes and the son of Agaue

- Pentheus' servant

- a herdsman

- Pentheus' attendant

- Agaue, the daughter of Cadmus and the sister of Semele

The Birth of Dionysus

We learn from Hesiod's Theogony (c. 8th century BCE) that Semele, the daughter of Cadmus (the king of Thebes), bore Dionysus prematurely upon having an affair with Zeus. Dionysus, in his prologue speech of the Bacchae, recounts how his mother was struck by Zeus' thunderbolt at the hands of a jealous and raging Hera. The chorus expands upon this in their first choral ode by singing of how Dionysus was:

Born

suddenly in labor

pangs brought on by force:

Zeus' thunderbolt took wing,

struck him out the womb.

His mother lost her life

in the flash of lighting.(Woodruff 4-5)

Blasted from his mother's womb prematurely, the chorus then tells of how Zeus sowed Dionysus into his thigh in order to hide him from Hera. In The Library, a work attributed to Apollodorus from the 2nd century CE, it is said that Hera had tricked Semele into asking Zeus to appear to her as he would to Hera. Unable to refuse, Zeus threw a lightning bolt, which subsequently killed Semele and caused her and Zeus' unborn child to be hurled from the womb. Following Semele's death, the writer of The Library claims that her sisters did not believe Semele's tale of having had an affair with Zeus, and it was her lie that caused her, in fact, to be struck down by a thunderbolt. In Euripides' Bacchae, it is for this questioning of his divinity that Dionysus has come to Thebes; he has made his way to the Greek city-state in order to avenge his mother's defamed reputation and, most importantly, to assert his true identity as a divinity.

Plot Overview

Prologue

Euripides' Bacchae takes place in the Greek city-state of Thebes, a location commonly used by ancient tragedians. Dionysus himself delivers the prologue speech, in which he reveals his true identity to the audience. Disguised as a stranger, he and his group of Maenads have traveled to Thebes from Asia, and he has chosen this city to be the first in Greece that worships him.

I came here—my first Greek city—

only after I had stated initiations there

and set those places dancing, so that mortals

would see me clearly as divine. Now Thebes,

is my choice to be the first place I have filled

with cries of ecstasy, clothed in fawnskin, put thyrsus

in hand—this ivy-covered spear—because my mother's

sisters—of all people, they should have known better—

said Dionysus was no son of Zeus. (6)

Dionysus has already begun the process of initiation, and he has caused the Theban women to abandon their homes for Mt. Cithaeron in order to partake in the worshipping of the god. He then concludes his speech by establishing that he will reveal to Pentheus his divine status and that he will force the city of Thebes to accept and acknowledge him as the divinity which he is.

Episode I

Following the prologue, Cadmus and Tiresias appear on stage dressed as worshippers of Dionysus. They both have acknowledged his divine nature and accepted his cult into Thebes. In the opening dialogue of the first episode, they discuss with one another where they should perform their dances. Cadmus asks Tiresias:

Where should we go to dance? Where plant

plant our feet and toss our heads, gray as they are?

By my guide in religion, Tiresias, the old leading

the old, since you're so wise. (8)

Pentheus then enters onto the stage with the seer and his uncle. Despite having been away from the city, he has heard about the shameful acts of the Theban women. According to the current king of Thebes, they are “pretending to be Bacchants,” but in fact, they are sleeping with other men instead of worshipping this fake god (9). Both Cadmus and Tiresias then plead with Pentheus to see reason, to proclaim that Dionysus is the son of Zeus. Tiresias criticizes the king:

When a prudent speaker takes up a noble cause,

he'll have no great trouble to speak well.

You, on the other hand, have a tongue that runs on smoothly

and sounds intelligent. But what it says is brainless. (11)

Cadmus echoes Tiresias' sentiment when he says:

Tiresias' advice is excellent, my boy. Stay home

with us, don't cross the threshold of law.

You are flitting about, you know, so thoughtless,

the way you think. (13)

Despite their attempts at persuasion and rationale, Pentheus refuses to acknowledge Dionysus as a god and the son of Zeus, and he vows to imprison the stranger that has infected his citizens with this madness.

Episode II

Pentheus and Dionysus meet on stage for the first time; however, Pentheus does not know that it is the god himself with whom he is speaking, and whom he has put in chains. Dionysus, as the stranger, informs Pentheus of his rituals. When Pentheus tells the stranger that he will remain under guard, the latter claims that Dionysus will release him from his imprisonment.

Dionysus. The god himself will set me free, whenever I want.

Pentheus. Sure he will, whenever you stand among your Bacchae and summon him.

Dionysus. Even now he's very near, and he sees what I am suffering.

Pentheus. Then where is he? He hasn't revealed himself to me.

Dionysus. He is where I am. You do not see him because you lack reverence. (20)

Dionysus adheres to his promise, and in the following episode, he escapes from his chains, causing Pentheus' palace to crumble. Pentheus meets with the stranger outside of his home and demands to know how he escaped. Dionysus and Pentheus are interrupted when the herdsman appears on stage in order to relate to Pentheus what he had just witnessed on Mt. Cithaeron. He and others had attempted to capture Agaue in order to bring her to the king; however, they were spotted by the maenads and were forced to flee. The herdsman then recounts the maenads' tearing apart of animals limb from limb and their destruction of the two villages Hysiae and Erythrae. He concludes by urging Pentheus to accept the worship of Dionysus, just as Tiresias and Cadmus had done in the first episode.

Episode III

Pentheus, in a state of disgust and outrage at the behavior of his female citizens, commands members of his army to prepare to fight the maenads. As the stranger, Dionysus warns the king of his actions and proposes an alternative. Dionysus asks Pentheus, “Would you like to see the women gathered on the mountain?” (32). Surprisingly, Pentheus enthusiastically agrees to see the maenads, despite the condition that he has to dress as a woman. Just as the King of Thebes does not know the true identity of the stranger, he is also ignorant of Dionysus' forthcoming punishment for his lack of reverence. Dionysus exclaims:

Now I'm off to get the fine clothes

I will fit to Pentheus for his trip to Hades when

his mother kills him. Then he will know the son of Zeus,

Dionysus, and realize that he was born a god, bringing

terrors for initiation, and to the people, gentle grace. (35)

Episode IV

Dionysus and a maddened Pentheus arrive on Mt. Cithaeron. The god informs Pentheus, “Your mental state used to be unhealthy. Not it is as it should be” (39). Dionysus exits the stage and the chorus yell their orders to the Maenads:

Run, swift hounds of madness, run to mountain!

Find where Cadmus' daughters hold their celebration,

Sting them to fury at the man

who parties in a woman's outfit

and spies in madness on Maenads. (41)

They then finish their choral ode by singing of the death of Pentheus.

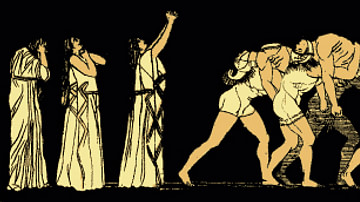

Episode V

The fifth episode opens with Pentheus' servant delivering the second messenger speech. This time, however, it is not animals that are being torn apart by the hands of the Maenads, but Pentheus. The messenger tells of Agaue who, while believing her son to be a dangerous lion, tore his body to pieces. Just as Pentheus did not recognize the god Dionysus, his mother did not recognize her own son. The other Maenads, Agaue's sisters, joined in the king's destruction:

Off went one with a forearm,

another took his foot—with its hunting boot. And his ribs

were stripped, flesh torn away. They all had blood on their

hands. They tossed Pentheus' meat like balls in a game of catch. (45)

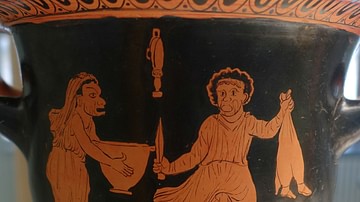

Exodus

Following the messenger's speech, Agaue enters the stage for the exodus. Still maddened and under the power of Dionysus, she carries Pentheus' head on a stick, proclaiming triumph over the lion which she believes she has killed. When Cadmus appears on stage he is shocked by the grisly image. He guides his daughter back to sanity, and Agaue truly sees what she is holding. Despite their worshipping of Dionysus, both Cadmus and Agaue are punished by the god, who banishes them from Thebes.

Agaue. I weep for you, Father.

Cadmus. And I for you, my child, and for your sisters. (47)

Analysis

Dionysus, the god of wine in Greek mythology, allows one to rid themselves of their inner inhibitions. In Euripides' Bacchae, he causes Pentheus to transcend both the physical boundaries of Thebes and those which he has placed around his mind. The king of Thebes works diligently to keep the corruption that Dionysus causes outside of his city, but not even he himself can resist its allure.

Many scholars have provided various readings of Euripides' tragedy. A.J. Podlecki describes the tragedy as follows:

[The Bacchae is a] poetic statement of the tensions set up between an individual and a group when that individual, after being a member, or even standing as head, of the group, with whose collective aims his own individual desires have been identified, suddenly — as often happens in ordinary life — finds himself outside the group, his own will in stark and even disastrous conflict with theirs. (Podlecki, 144).

On the other hand, Christine M. Kalk analyzes the physical transformation that Pentheus undergoes throughout the tragedy, specifically how he metamorphizes from the King of Thebes into a symbol that represents the thyrsus. This transformation illustrates Dionysus' true power. Jean A. LaRue argues that Pentheus is controlled by his sexual obsession with the Maenads. To quote LaRue, “Pentheus' pride struggles with his lustful curiosity, and the latter wins” (LaRue, 212).

Legacy

The influences of Euripides' corpus can be found not only in the tragedians of the 4th century BCE but also in the works of the Greek comedy playwrights of the 4th and 3rd centuries BCE. To quote Bernard Zimmermann, "Through the Roman playwrights Plautus, Terence, and Seneca he left his mark on the whole subsequent tradition of European drama," (Zimmermann, 87).

Euripides portrayed his characters in ways that closely resembled the individuals of his Athenian audience, and they continue to bear semblance to modern readers. With specific regard to the Bacchae, Euripides forces one to question who Dionysus and Pentheus truly are. What part of one's own inner being do both characters represent? How is one better able to understand their own self upon reading the tragedy?