Bacon’s Rebellion (1676) was the first full-scale armed insurrection in Colonial America pitting the landowner Nathaniel Bacon (l. 1647-1676) and his supporters of black and white indentured servants and African slaves against his cousin-by-marriage Governor William Berkeley (l. 1605-1677) and the wealthy plantation owners of East Virginia.

The conflict began over the fair distribution of land rights and Bacon’s proposal to remove or eradicate the Native Americans who still lived in the region following the Anglo-Powhatan Wars (1610-1646). Bacon died of dysentery after burning Jamestown and the rebellion was crushed by Berkeley.

The rebellion was later characterized as a precursor to the American War of Independence (1775-1783) in that it was interpreted as a revolt against British authority to establish colonial autonomy. Actually, Bacon’s Rebellion had nothing to do with colonial objections to British rule and everything to do with colonial greed and corruption. Bacon was right in accusing Berkeley of favoring his friends in trade agreements and land sales, and Berkeley was right in charging Bacon with treason and vigilantism against Native Americans. The revolt is better understood as a conflict between the elite owners of large plantations near the coast and those who kept smaller farms inland who were joined by landless servants and slaves.

The rebellion is significant in that it was the first to unite black and white indentured servants with black slaves against the colonial government, and, in response, the government established policies to ensure nothing like it would happen again. New legislation resulted in the dissolution of the indentured servant policy, an increase in the slave trade, the encouragement of the ideology of white supremacy, and further loss of land and rights for Native Americans. The aftermath of Bacon’s Rebellion, in fact, can be understood as establishing institutionalized, systemic racism in the English colonies which would become the United States of America.

Tobacco, War, & Land

The rebellion began over the conflict between landowners in the interior and the more affluent plantation owners along the coast of Virginia. The Jamestown Colony of Virginia was founded in 1607, and tobacco began to be cultivated on large plantations in the east after tobacco seeds were brought to the region by John Rolfe (1585-1622) in 1610. Rolfe’s tobacco, which was sweeter than others on the market at the time, became Jamestown’s cash crop, and more farmers began planting tobacco than other crops such as corn or rice. Tobacco’s popularity abroad encouraged the establishment of more and more plantations, which encroached on Native American lands resulting in the Anglo-Powhatan Wars of 1610-1646.

The First Powhatan War (1610-1614) had little to do with tobacco per se but did arise out of the land-grabbing policies of the colonists and the refusal of Jamestown’s governor, Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (l. 1577-1618) to compromise and address Native American concerns. Land was purchased for less than it was worth because the natives of the Powhatan Confederacy did not have the same concept of property rights as the English and so, to them, the transaction was more of a rental than a sale; the indigenous people believed they were only giving the English the right to use their land, not to own it.

The first war was ended by the Peace of Pocahontas after Pocahontas (l. c. 1596-1617), daughter of the Powhatan chief Wahunsenacah (l. c. 1547-c. 1618), married John Rolfe. During this period of peace (1614-1622), more land was taken for tobacco cultivation and was worked by indentured servants. These were individuals who had agreed to work for seven years in return for passage to North America and, at the end of their servitude, to be rewarded with their own land. In 1619 CE, the first Africans arrived in Jamestown and were purchased by then-governor Sir George Yeardley (l. 1587-1627) to work his fields.

Although these 20 Africans had been taken as slaves by the Dutch (whose ship put in at Jamestown only for supplies, not to sell slaves), a number of scholars (David A. Price among them) argue that they were not treated as slaves upon their arrival but more along the lines of indentured servants. Slavery had not yet been institutionalized in the colonies and had been outlawed in England centuries before and so it is reasonable to suggest that the Africans would have been subject to the only system of servitude the colonists knew. Further, indentured servitude was hardly a novel practice in the colonies and the Africans would have most likely been acquainted with it.

The Second Powhatan War broke out with the Indian massacre of 1622 in which over 300 colonists were killed by the Powhatan chief Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646). When the war ended with an English victory in 1626, more land was taken from the Powhatans and turned into farmland and settlements. From 1614 onwards, every seven years, roughly, another group of indentured servants were released from their contract and received land and, while this was going on, more and more were arriving from England who had made the same arrangements and so even more land was required.

After the Third Powhatan War (1644-1646), the Powhatan Confederation was dissolved, and large tracts of land taken by the colonists. The Native Americans were pushed into the interior but, as more colonists had been receiving land regularly since c. 1614, this area was also where former indentured servants were now settling on their promised acreage. Tribes formerly associated with the Powhatan Confederacy, as well as others, understood this land as theirs and periodically raided settlements, killing the colonists. During this same time, slavery was first introduced as a legal option for punishment in 1640 establishing a class of African slaves as the lowest and thereby elevating the status of indentured servants and other landless citizens, both black and white.

Berkeley, Bacon, & the Native Americans

The best lands were those already claimed by aristocrats along the east coast of the Virginia Tidewater. These had expanded during the Peace of Pocahontas, others were established after the Second Powhatan War, and still others developed through the sale of parcels by the owner to newly-arrived members of their same social class; one of these new immigrants was William Berkeley. Berkeley had been a courtier in the palace of Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) since 1632, had been knighted for his service to the crown, and so was well connected. He was appointed governor of the profitable Virginia colonies in 1641 and established his own plantation (Green Spring House) near Jamestown among the other elite.

Berkeley led the attack on the Powhatans which ended the Third Powhatan War in 1646 and stipulated the terms of the treaty which, officially or not, included a monopoly on the deerskin and fur trade for himself and his friends. When Charles I was deposed and executed in 1649, Berkeley offered a safe haven to royalist friends, was censured by the new government, and resigned his position as governor in 1652, but was allowed to keep his lands and continued his trade relations with the natives.

Nathaniel Bacon was the son of wealthy landowners in England, was also well-connected, and was related to Berkeley through marriage. He had spent his youth in study at Cambridge and traveling through Europe at his parents’ expense, but c. 1665 he was accused of cheating an acquaintance out of his inheritance and could expect serious repercussions for it. Rather than allow his son to face the consequences of his actions, Bacon’s father sent him to Virginia with a considerable sum of money. Bacon purchased land a few miles from Jamestown in the same upper-class region as Berkeley and the others. By this time, Berkeley had regained his position as governor and appointed Bacon to his council.

By 1675, a significant number of indentured servants, both black and white, had long before completed their terms of service and now owned small farms throughout Virginia. As noted, however, the choice lands were owned by the upper-class and sold only to members of the same. With more colonists coming every year, more land was taken from the Native Americans even though they had been promised land rights after the Third Powhatan War. Native American raids continued to strike the small farms of the interior which destabilized trade and commerce.

Bacon advocated for the removal or wholescale slaughter of the indigenous tribes but Berkeley, who was making considerable profit from trade with them, initiated a policy of defense and containment, ordering the construction of a number of forts along the Virginia frontier. Bacon objected on the grounds that this measure would only raise taxes and would not stop the raids. He charged Berkeley with corruption on the grounds that he gave preferment in government positions to friends and relatives (as he had with Bacon himself), was profiting from trade with the natives (which only upset Bacon because Berkeley refused to cut him in on the trade), and was enriching himself at taxpayer expense (as Bacon was most likely also doing).

Bacon’s Rebellion

Bacon outlined his objections in his Declaration of the People of Virginia, issued 30 July 1676 which charged Berkeley with corruption on eight separate counts. Bacon presented each count in full but never mentioned how he had himself benefited from Berkeley’s policies. He presented himself as a man of the people, who was willing to fight for the farmers of the interior against the injustices perpetrated by the elite of the coast, and to prove himself as good as his word, he led vigilante raids against the natives. Scholar Alan Taylor comments:

To popular acclaim, Bacon led indiscriminate attacks on the Indians, in open defiance of the governor. Bacon demanded that the colonists destroy "all Indians in general for…they were all Enemies." Because friendly Algonquians were closer and easier to catch, they died in greater numbers than did the hostile and elusive Susquehannock. In 1676, Berkeley declared Bacon guilty of treason which led Bacon to march his armed followers against the governor in Jamestown. (149)

By this time, Bacon’s followers numbered between 300-500 armed men who had been seduced by promises he had no way of keeping. Bacon promised freedom for indentured servants (who made up the majority of his supporters), lower taxes, better lands for freemen, and security for the farmers of the interior through the elimination of Native Americans. Black and white indentured servants and farmers, as well as slaves, joined the cause as Bacon further fired class resentment by telling them that their economic problems and, in some cases, poverty were caused by the wealthy landowners who kept the best resources for themselves and were being protected and encouraged in this by Berkeley’s corrupt administration. He further accused Berkeley of being pro-native and of valuing Native American rights above those of English colonists.

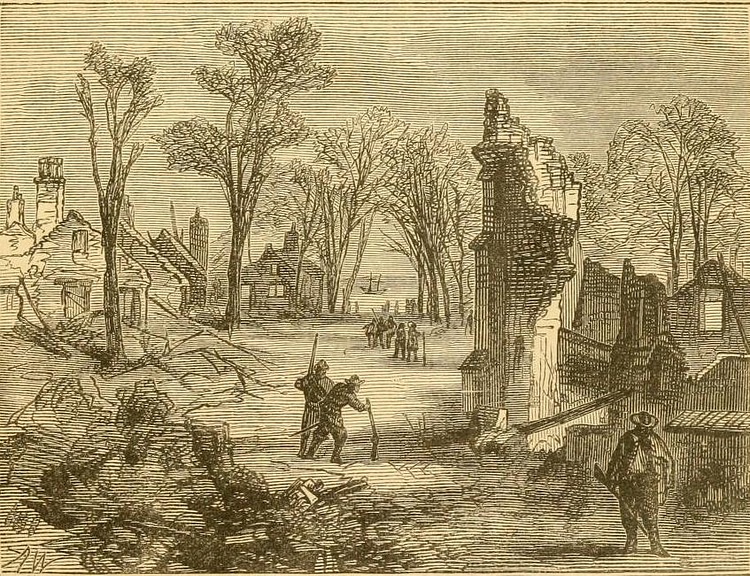

Berkeley denied any wrongdoing and maintained his charge of treason against Bacon. Bacon responded by clearly stating he had no quarrel with the crown – and was therefore not guilty of treason - but only with Berkeley and his corrupt practices. Bacon felt he had now exhausted legal and diplomatic avenues and marched his followers on Jamestown. Berkeley, his household, and supporters fled the town as Bacon marched in and, finding them gone, burned the place to the ground. They then occupied the ruins and waited for the expected military response from Berkeley.

Before that came, however, Bacon died of dysentery in October of 1676. Another man, John Ingram, took charge, but he was not as charismatic as Bacon, and the mob began to steadily dissipate and return to their homes. Berkeley then launched an attack, disarmed the rebels who were left, and hanged 23 of the leaders, ending the rebellion. Ingram, who is unknown outside of his participation in the uprising, was almost certainly among those hanged.

Conclusion

Berkeley felt he had done well, but this opinion was not shared by King Charles II of England (r. 1660-1685) who ordered him back to England to explain himself. Berkeley’s wife is said to have consoled him in that the king would surely pardon him of any perceived errors because he had kept the peace. Based on accounts of Charles II’s reaction to news of the rebellion, however, their meeting almost certainly would not have gone as Mrs. Berkeley hoped, but there is no way of knowing because Berkeley died shortly after arriving in England.

Charles II had sent Sir Herbert Jeffreys to order Berkeley back home and now Jeffreys took control and tried to dismantle the power structure of the elite Virginian planters. With over 200 troops under his command, Jeffreys restored order and then turned his attention to reducing the wealth and power of the elite plantation owners but died in 1678 before anything could be accomplished.

The wealthy landowners, who were either members of or influential with the legislative body of the House of Burgesses, recognized they had narrowly escaped disaster and took measures to ensure nothing like Bacon’s Rebellion would happen again. They first passed legislation barring indentured servitude since it was clear that the proliferation of small farms had only created a disgruntled and heavily armed citizenry. They then further institutionalized racial slavery, which had been growing in practice since the 1660s, and established Jamestown as a major port of the slave trade.

Taylor notes, "slave numbers surged from a mere 300 in 1650 to 13,000 by 1700, when Africans constituted 13 percent of the Chesapeake population" (154). Black people were increasingly associated with a lower slave class and, in order to further prevent black and white farmers from banding together again, the assembly reduced the poll tax so that the greatest burden fell on the poorer farmers, many of whom were black. These measures encouraged the ideology of white supremacy in that class differences between poor and wealthy whites were minimized as racial differences between whites and blacks were emphasized.

To pacify the farmers of the interior, the House of Burgesses also reinstituted the headright system which promised any freeman 50 acres of land taken from the Native Americans. The headright system encouraged further colonization and slaughter of natives on lands they had been promised by the Treaty of Middle Plantation in 1677. After Bacon’s Rebellion and the new legislation, more land was taken, and the Native American reservations shrank further than they already had.

A little over one hundred years after the event, Bacon’s Rebellion was regarded by some, such as Thomas Jefferson, as a precursor to the American War of Independence and Bacon as a great patriot. This view of the rebellion and its leader persisted, especially in Virginia, through the 20th century and still appears in some texts in the present day. Bacon himself made it clear, however, that he was not rebelling against British rule but only against Berkeley and his administration.

Bacon’s motivation appears far less noble when one considers that his objections to Berkeley’s policies were motivated by his own greed, racism, genocidal policies, and disappointment that Berkeley was not sharing trade resources with him. Bacon’s Rebellion, far from a patriotic uprising, was nothing more than another example of English colonial greed with the aftermath resulting, as usual, in non-white, non-English populations paying the price for those who already had well beyond what they needed to have even more.