Baldr is a god in Norse mythology associated with light, wisdom, and courage, although he is never specifically defined as the god of any of these. He is best known for his dramatic death, which heralds the coming of Ragnarök, the end of the age of the Norse gods and the rebirth of the world.

Baldr (also given as Baldur, Balder) is the son of Odin and Frigg. His name might mean "Lord" but is also associated with "day" and "courage". Scholars continue to debate the name’s meaning but generally seem to accept the mythographer Jakob Grimm’s claim that it means "shining" or "shining one".

The story of his death is told fully in the Prose Edda by the Icelandic mythographer Snorri Sturluson (l. 1179-1241) but is referenced in the Poetic Edda. In the story woven from both these works, Frigg extracts a promise from all living things not to harm Baldr but ignores the mistletoe which the trickster god Loki then uses to kill the god. Baldr is mentioned in other works, however, and in the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus (l. c. 1160 - c. 1220), he is a prince named Balderus at war with another, Hotherus, for the hand of the princess Nanna. In this version, he is killed by Hotherus wielding a magical sword called Mistletoe.

Both of these versions – and others less well known – derive from an earlier tale, possibly based on an actual event in which a man killed his brother and, in an age when blood had to be avenged by blood, the father was helpless to punish the murderer. This theory is advanced by scholar John Lindow, who claims the Baldr myth illustrates the impracticality of the blood feud at a time when men were considered "sons of Odin" and brothers in blood. The myth seems to resist this interpretation, however – at least as presented in the Eddas – because Odin impregnates the giantess Rindr to have a son, Váli, who avenges Baldr and so meets the demands of family honor.

In the Icelandic Prose Edda and Poetic Edda, Baldr is depicted ideally as epitomizing light, wisdom, affability, and nobility, while in the Danish work of Grammaticus, he is drawn more realistically. The modern-day video game God of War follows the Danish vision in depicting Baldr as a rugged warrior instead of a shining god.

Oral Tradition & Early Tale

It is possible that the figure of Baldr was originally based on a Germanic noble as the Proto-Germanic name Baldraz means "prince" (or "hero"). There is no way of ascertaining this, however, as there is no written record. Early Nordic written communication took the form of runes, which were not used for relating long stories; that was the job of the poets who maintained an oral tradition. Lindow comments:

The oldest runic inscriptions are from around the time of the emergence of the Germanic peoples and are written in an alphabet of 24 characters whose origin is greatly debated…Most [runic inscriptions] are memorial: They explain who erected the stone, whose death is memorialized, and what the relationship was between the two. Although the few rune sticks and other kinds of runic inscriptions that have been retained show that runes could be used in a great many ways, Scandinavia through the Viking Age was for all intents and purposes an oral society, one in which nearly all information was encoded in mortal memory – rather than in books that could be stored – and passed from one memory to another through speech acts. Some speech acts were formal in nature, others not. But like speeches that politicians adapt for different audiences, much ancient knowledge must have been prone to change in oral transmission. (11-12)

The Baldr tale could have originally been, and probably was, a formal speech relating the tragic death of a prince, which, in time, was elevated to a tale of the gods and of one god in particular, an innocent, whose unjust death signals the end of the ordered world. It is equally possible that the tale was always about the gods and the death of Baldr, "the shining one", foreshadows the deaths of the other gods at Ragnarök and the destruction of the shining realm of Asgard.

In the Poetic & Prose Edda

The poets (skalds) would have sung the tale for audiences who would have retained the basics and passed the story on. This oral tradition was maintained until c. 1000 when Christianity became widely accepted in the region and earlier legends, tales, and myths were committed to writing. Many older works were written down in the 10th century that served as sources for later writers. The Poetic Edda (compiled in the 13th century) preserves many of these while Sturluson’s Prose Edda presents many of the same stories in narrative form.

In the Poetic Edda, Baldr features in the Völuspá ("The Witch’s Prophecy"), the Lokasenna ("Loki’s Taunts"), Baldrs Draumar ("Baldur’s Dreams"), and the Völuspá hin skamma ("Short Völuspá"). In the Prose Edda, his story is given in the section Gylfaginning ("The Beguiling of Gylfi") in its most complete form. Although Sturluson is understood to have drawn on earlier myths, it has also been recognized that he added to these and so the best-known version of Baldr’s death is thought to be largely Sturluson’s 13th-century creation. This claim is based on the pieces from the Poetic Edda and allusions to the tale elsewhere but, like any theory involving pre-Christian Norse mythology, cannot be proven as there is no written record. It is possible Sturluson took the story from an earlier piece later lost.

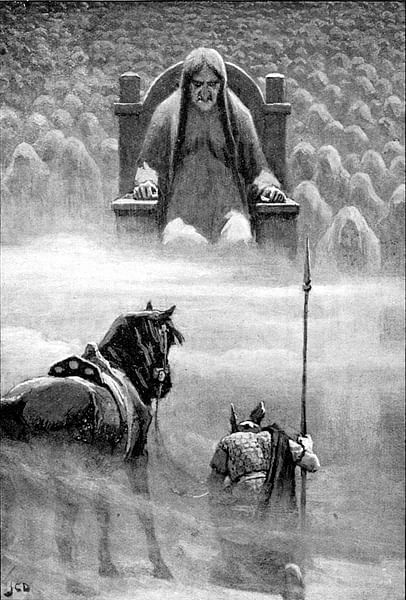

Whatever Sturluson added, or if he added anything, the story begins with the events narrated in brief in the poem Baldur’s Dreams. Baldr has been having nightmares of some impending doom he cannot see, and Odin rides Sleipnir down to Hel, the realm of the dead, and raises the spirit of a völva ("seeress") to find out what the dreams mean. Sturluson picks up the tale at this point when Frigg goes throughout the Nine Realms of Norse cosmology extracting a promise from all things, animate and inanimate, that they will not hurt her son. All things make the promise and, afterwards, the gods of Asgard develop a funny game of hurling things at Baldr to watch them bounce off him.

Loki, observing this, transforms himself into a woman and goes to visit Frigg in her grand hall. Frigg asks the visitor what the gods are up to in Asgard, and "she" tells her that they are at their usual sport of lobbing objects at Baldr. The visitor then coyly asks if it is really true that all things promised never to harm Frigg’s son, and she answers that she never extracted a promise from the mistletoe because it was so young and harmless.

Loki hurries away, finds some mistletoe west of Valhalla, and fashions it into a projectile. When he returns to Asgard, the gods are still at their game, and Baldr’s blind brother Hodr is standing to one side, sad because he cannot participate in the fun. Loki places the mistletoe in Hodr’s hand and says he will guide his aim. Hodr throws the mistletoe that kills Baldr instantly.

The gods are all horrified, and Frigg cries out for a volunteer to ride to Hel and ask for Baldr’s return. The god Hermodr, referenced as Baldr’s brother, is given Sleipnir and takes off for Hel while the others prepare Baldr’s funeral. Baldr’s wife, the moon goddess Nanna, either dies of grief or kills herself when Baldr is placed on the pyre aboard his great ship Hringhorni. The gods are all in attendance, and Odin whispers something to Baldr’s corpse before Thor tries, and fails, to launch the ship. The giantess Hyrrokkin is summoned from Jotunheim who shoves the great boat into the sea, causing flames to flash and earthquakes which anger Thor, who felt he could have done the job better. As the flames engulf the corpses of Baldr and Nanna, Thor angrily kicks the dwarf Litr – who seems to have merely been running past – onto the ship, burning him alive.

Hermodr, meanwhile, has arrived in Hel and asks the Queen of the Dead for the return of Baldr and, as he now sees, Nanna as well. Hel agrees on the condition that all things in the Nine Realms weep for Baldr. Hermodr leaves and gets everything to mourn the fallen god except for the giantess Thokk (Loki in disguise) who refuses. Baldr and Nanna then have to remain in the land of the dead until Ragnarök when they will return at the rebirth of the world.

Odin mates with the giantess Rindr who gives birth to a son, Váli, who grows to maturity in a day and kills Hodr to avenge Baldr. Afterwards, at a banquet of the gods, Loki insults everyone present until Thor shows up and threatens to beat him and the gods then imprison Loki under the earth in a cave with a serpent above him dripping venom on his head. This punishment is said to be for his role in Baldr’s death and the insults at the banquet. Loki and his children, Fenrir the wolf, Jörmungandr the serpent, and Hel, Queen of the Dead, will all remain in their respective prisons until the dawn of Ragnarök when they break free and confront the gods of Asgard and the Heroes of Valhalla in the final great battle.

Saxo Grammaticus’ Baldr Tale

Grammaticus’ tale of Baldr retains the nobility of the central character but humanizes him as well as all the others. Although there are magical elements to the story, it is given as history in the Gesta Danorum III. 70-81. In this version of the story, Balderus is a demigod who is in love with the princess Nanna, daughter of the king of Norway, who is also being pursued by the hero Hotherus. Balderus is supported by a group of women (possibly Valkyrie) and the gods, specifically Odin and Thor.

The women keep Balderus strong with a special food they serve him, making him invincible, and since he is a demigod, he cannot be slain by any weapon made by mortal hands. Hotherus goes to the women to ask them for help, and they agree to give him a magic belt that will bring him victory as well as some advice but refuse to help him kill Balderus. Hotherus meets Balderus and the gods in battle and defeats him after cutting off the handle of Thor’s hammer. They meet again and, this time, Balderus is victorious but still cannot win Nanna’s hand because she does not want to marry a demigod and marries Hotherus.

Balderus becomes love-sick and falls into such a deep depression that he cannot walk and has to be pulled around in a wagon. Balderus, even in his weakened state, still is able to cause problems for the couple and so Hotherus again tries to find some way to kill him. He discovers that Balderus can only be slain by a magic sword known as Mistletoe which is guarded by a satyr (or troll) in the underworld. Hotherus makes the long, dangerous journey, defeats the guardian, and returns to the mortal realm with Mistletoe.

When Balderus mounts another attack on Hotherus, Hotherus wounds him with the magic sword, and Balderus dies three days later. He is given a royal funeral and interred in a great barrow. Odin swears he will avenge Balderus and is told by a sorcerer that he must impregnate the princess Rinda, daughter of the king of the Rutenians. Odin first attempts to seduce Rinda in the form of a warrior, then as a smith, and then as a knight, but she rejects his advances.

He then transforms himself into a woman and serves as one of Rinda’s handmaidens while letting it be known that she has special powers of healing. When Rinda falls ill, Odin-as-maiden orders her tied down so she can be given medicine, assumes his actual form, and rapes her. She gives birth to the hero Bous who later kills Hotherus and avenges Balderus.

The Dying & Reviving God

The stories are significantly different even though they share some striking similarities, and other Danish chronicles echo Grammaticus’ version. This has suggested to some scholars that the story may have originated in Denmark as the tale of the death of a prince or hero, which was then transformed into a tragedy concerning the gods. Sturluson’s version has often been cited as an example of the motif of the dying and reviving god – a deity who gives his or her life for the greater good of the people and returns in some form – that appears in the mythology of many different ancient cultures. The most famous example of this figure is Jesus Christ, but many earlier religions feature the same character, notably ancient Egypt with Osiris.

The claim of Baldr as the reviving god was most famously advanced by the folklorist and scholar Sir James George Frazer (l. 1854-1941) in his influential 1890 work The Golden Bough. The death of Baldr as an example of the dying and reviving god has been repeated by other writers, with more or less the same reasons, ever since. The problem with this claim is that neither the myth nor Grammaticus’ "history" supports it. In Sturluson’s version, Baldr dies, goes to Hel, and is unable to return when Thokk refuses to cry for him. Although he comes back from the land of the dead at the rebirth of the world, he does not in any way bring about that resurrection and he is given no greater place among the survivors of Ragnarök than any of the others. In Grammaticus’ story, Balderus shrivels from lovesickness and when he is defeated and killed, he is buried and life goes on.

This claim continues to be repeated, however, as scholars argue over whether the Baldr myth was an old tale of a dying and reviving vegetation god that was later Christianized or was largely Sturluson’s creation drawn from the few references to Baldr’s death in the works of the Poetic Edda. There is no way of knowing whether some tale of Baldr existed in pre-Christian Scandinavia or Iceland, as noted, but it is clear from the extant works that Baldr was not a dying and reviving God because he does not return from the dead until the Nine Realms, including Hel, have been destroyed and there is nothing to hold him in death’s land anymore. Unlike Osiris or Jesus or Inanna or any other dying and reviving deity, Baldr does not die to later benefit anyone; his death, in fact, signals the destruction of the world.

Conclusion

Lindow rejects the claim of Baldr as a reviving god on the commonsense grounds that it is not supported by the stories. Lindow theorizes that it is more likely an illustration of the impossibility of resolving differences through blood feuds:

I understand the story as the mythic reflection of a basic social problem, namely, the fact that a society that used blood feud to resolve disputes could not deal with a killing within a family. Simply by requiring a counterattack against the family of the killer, Hodr’s killing of Baldr puts Odin in an impossible situation. (69)

Although an interesting observation, Lindow himself admits that Odin just "displaces the problem of brother killing brother" by engendering Váli to kill Hodr, but he still observes the code of the blood feud. The story of Baldr’s death has too much resonance and seems to have been far too popular to have only been a mythic representation of an aspect of Norse culture no one seems to have questioned or had a problem with at all.

Baldr’s story most likely resonated with an ancient and medieval audience for the same reason it does in the present day: because it is a tragedy, and tragedies have always been a popular form of entertainment. As Aristotle observes, tragedy features a main character of noble stature who suffers defeat and death, providing an audience with a kind of relief (catharsis) in that they are not alone or unique in dealing with the more difficult aspects of life.

In Grammaticus’ version, the noble prince, even supported by the gods, does not get the princess of his dreams and is instead defeated and killed. In Sturluson’s, the shining god, most beloved of all the gods, is murdered for no reason, unwittingly, by his brother who then must die to uphold the family honor. At its most basic level, Baldr’s story highlights the unpleasant reality of life that one does not always, or even often, get what one wants, and good people suffer and die unjustly.

The message one might have taken from the tale was that if injustice and suffering could befall a god or prince, it could as easily be visited on anyone, and some comfort could be gained in recognizing that anyone, even a god, could be brought down for no good reason. One’s personal suffering might then be alleviated in not only mourning for Baldr but in empathizing with all those who grieve for what is lost.