Banastre Tarleton (1754-1833) was a British military officer and politician, most famous for his role in the southern campaigns of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). In command of an elite unit of Loyalists called the British Legion, Tarleton gained a reputation for aggression and cruelty, with Patriots even coining the phrase 'Tarleton's Quarter' to refer to his mercilessness.

Tarleton joined the British Army in April 1775 at age 20 after blowing through his inheritance. Sent overseas to fight the American rebels, he soon became one of the most infamous British officers of the conflict. Called 'Bloody Ban' after his men massacred surrendering American soldiers at the Battle of Waxhaws, Tarleton led his British Legion on raids throughout the American South, their plumed leather helmets and green jackets striking fear into the hearts of many Patriots. Defeated by Daniel Morgan at the Battle of Cowpens (17 January 1781), Tarleton nevertheless managed to return to England after the war with his reputation intact. He began a long political career in Parliament, in which he notably defended the slave trade, before his death on 15 January 1833 at the age of 78. He is best remembered today for his ruthlessness during the war, although many tales of his cruelty have been exaggerated.

Early Life

Banastre Tarleton was born in Liverpool, England, on 21 August 1754, the third of seven children born to John Tarleton and his wife Jane Parker. John Tarleton was a successful businessman involved in the Caribbean sugar trade and owned plantations in Jamaica, Curaçao, and several other islands in the West Indies. By the 1760s, the elder Tarleton owned three ships that were primarily used to deliver enslaved Africans to Jamaica; indeed, much of the Tarleton family's wealth was derived from the slave trade. In 1764, John Tarleton (or 'Great T' as he was called by his constituents) was elected mayor of Liverpool and served a single one-year term. In 1768, the elder Tarleton tried to stand for election to Parliament, but a mob of whalers prevented him from running.

Banastre (or Ban, as he preferred to be called) attended school in Liverpool. Intelligent, handsome, and charming, he was not a diligent student, preferring to spend his time playing cricket; despite his small physique, he was surprisingly strong and enjoyed many other athletic activities like boxing, horseback riding, and tennis. In the autumn of 1771, Ban and his older brother Thomas were sent to Oxford to study at University College. Tarleton remained there until 6 September 1773, when his father unexpectedly died, leaving him an inheritance of £5,000. With this small fortune, Tarleton headed to London to begin studying law at the Middle Temple. His studiousness had not much improved, however, as Tarleton often neglected his studies in favor of attending the theatre or drinking and gambling at the fashionable Cocoa Tree club. It was not long before he had nearly exhausted his inheritance, forcing him to drop out of law school.

During this period of adolescent partying, the wayward Tarleton befriended several British army officers, who likely helped put his thoughts on a military path. On 20 April 1775, the 20-year-old Tarleton purchased a cornet's commission in the King's Dragoon Guards, one of the most prestigious regiments in the entire army. It was an interesting time to enter military service, as only the day before, the Battles of Lexington and Concord had been fought on the other side of the Atlantic in the British colony of Massachusetts, sparking the American Revolution. After several months of intensive training, Cornet Tarleton was finally sent to North America in February 1776, setting sail from Cork, Ireland, under the command of Lord Charles Cornwallis. Little did Tarleton know that by the time his service in the New World was over, he would be regarded as one of the most infamous men in America.

Arrival in America

The ships bearing Cornwallis' troops across the Atlantic reached Cape Fear, North Carolina, on 3 May 1776. Here, they joined forces with another British detachment under the command of General Henry Clinton, and together, they set sail for Charleston, South Carolina, the largest and most important city of the American South. Tarleton witnessed the failed British attack on the city, known as the Battle of Sullivan's Island (28 June), from the deck of a Royal Navy warship, but if he had any striking thoughts after experiencing a battle for the first time, he did not record them. Following this defeat, the expedition sailed back north to join the main British army under commander-in-chief Sir William Howe, gathering on Staten Island. On 27 August 1776, the British assaulted the American defensive position at the Battle of Long Island; although Tarleton's exact location during this battle is unknown, he was most likely with Cornwallis' reserve division, marching behind Clinton's vanguard. He may even have had his first combat experience when Cornwallis' men beat back six desperate charges from a regiment of Marylanders.

The battle resulted in a decisive British victory, ultimately leading to the British occupation of New York City on 15 September. For the remainder of the autumn, Howe's British troops pursued the ragged Continental Army in the New York and New Jersey Campaign, but despite a string of victories, they were unable to pin the Americans down and deal a decisive blow. Tarleton played his part in the campaign; having volunteered to serve with the 16th Regiment of Light Dragoons under Lt. Colonel William Harcourt, Tarleton was often sent ahead of the main British army to conduct scouting missions and raiding parties. On one such reconnaissance mission, early on the morning of 13 December, Tarleton was gathering information on the whereabouts of an American force under Major General Charles Lee in New Jersey. Tarleton and his men discovered that Lee was spending the night 3 miles (5 km) away from his men at White's Tavern, and the young cornet wasted no time surrounding the tavern and capturing Lee, who was still in his nightgown when he was taken prisoner.

The capture of Lee, George Washington's second-in-command, was a significant blow to the American cause and earned Tarleton promotion to the rank of brigade major. Although things currently looked dire for the withering Continental Army, Washington would soon turn the tables with his stunning victories at the Battle of Trenton (26 December 1776) and Battle of Princeton (3 January 1777). After these battles, Howe changed his strategy and decided to target the United States capital of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, capturing the city on 26 September 1777 after a brief campaign. The British army wintered in occupied Philadelphia, where the officers spent their time courting Loyalist women and attending lavish balls. No stranger to parties, Tarleton certainly reveled in the fun. On 18 May 1778, he took part in the Mischianza, an extravagant, city-wide festival put together by his friend Captain John André as a farewell party for Howe, who was returning to England. The festival included a mock tournament play-acted by 14 officers dressed as medieval knights, including Tarleton.

Bloody Ban

On 18 June 1778, Sir Henry Clinton – who had replaced Howe as British commander-in-chief – was ordered to evacuate Philadelphia so that he could consolidate his forces in Manhattan. Shortly after his return to New York, Clinton created the British Legion by merging several smaller companies of American Loyalists into a single elite unit. Tarleton was promoted to lieutenant colonel and named as second-in-command to the Legion's colonel, Lord Cathcart. Over the course of the next year and a half, Tarleton took part in several minor raids in southern New York. In March 1780, he accompanied Clinton's main army on another expedition to Charleston; this time, the attack proved successful, as Clinton's British soldiers dug siegeworks on the landward side of the city and blockaded the harbor by sea.

Since Lord Cathcart had stayed behind in New York, Tarleton assumed operational command of the British Legion, which quickly became associated with him. As the Siege of Charleston progressed, Tarleton was ordered to capture all the main crossing points over the Cooper River, the only route the American defenders of Charleston could use to escape the city. Tarleton swiftly carried out these orders, chasing off the American troops guarding the pass at Monck's Corner after a brief skirmish on 14 April 1780. Within the next 24 hours, Tarleton captured every other major river crossing within 6 miles (10 km) of Charleston, helping to seal the fate of the city. On 12 May, American General Benjamin Lincoln surrendered the city and his entire army of 5,466 officers and men, marking the greatest British victory of the war. Clinton, hoping to mop up the remaining vestiges of the southern Continental Army scattered throughout South Carolina, sent Tarleton and the British Legion out to deal with them.

On 6 May, Tarleton surprised a small company of Virginian dragoons at Lenud's Ferry as they were crossing the Santee River. 36 Americans were killed or wounded in the skirmish, several of whom drowned as they attempted to swim across the river to escape Tarleton's clutches. The British Legion pressed on, in pursuit of a Virginia regiment that was fleeing toward the safety of North Carolina. Tarleton rode his men hard, covering 105 miles (169 km) in 54 hours and leaving a trail of dead horses in his wake, before finally catching the Virginians on 29 May 1780 at Waxhaws. The experienced British dragoons charged into the line of raw American recruits, who before long were trying to surrender; the troopers of the British Legion, however, ignored their calls for mercy, even cutting down a white flag raised by one of the Virginians. The frenzied slaughter continued for some time, with the Tarleton's men even skewering corpses with their sabers to make sure that they were dead. When the dust settled, 113 Virginians were dead and 203 were wounded; of these wounded, 150 were so severely injured that the British left them to die on the bloodstained field, unable to carry them off as prisoners.

The Battle of Waxhaws was a watershed moment in Tarleton's career. Before it, he had been unknown; now, he was infamous. American Patriots vilified him as a bogeyman, calling him 'Bloody Ban'. The phrase 'Tarleton's Quarter' came to refer to the ruthlessness exhibited by Tarleton and other British officers and became a battle cry for Patriots in the same way that 'Remember the Alamo' or 'Remember Pearl Harbor' electrified future generations of U.S. soldiers. Tarleton would always deny his responsibility for the massacre; in his memoirs, he would claim that his horse had been killed from under him and that he had been pinned to the ground by its corpse for most of the battle. His men, believing that their beloved colonel had been killed, carried out the murderous slaughter in a mad fit of revenge that he had been unable to stop. Such, at least, was Tarleton's claim. The incident also turned him into a war hero in Britain, where the more unsavory details had been left out of public reports.

Southern Campaign

A few days after Waxhaws, Clinton returned to New York with a large portion of the army, leaving Lord Cornwallis behind to finish the conquest of the Carolinas. Cornwallis relied heavily on Tarleton's speed and newfound reputation for ruthlessness, unleashing him like a mad dog to chase down Patriot partisans and guerilla fighters in the South Carolina backcountry. Tarleton spent much of his time hunting Patriot militia leaders such as the 'Swamp Fox' Francis Marion, whose guerilla tactics had proved a thorn in the British side. Tarleton was never able to capture Marion, but his attempts to do so earned him the ire of the local population, as he burned and raided the properties of South Carolinians suspected of harboring Marion's rebels.

Tarleton played an important role at the Battle of Camden (16 August 1780); after Cornwallis crushed Horatio Gates' American army, Tarleton's Legion was sent to drive the surviving Continentals from the field. Only a few days later, Tarleton chased Thomas Sumter's militia force to Fishing Creek, killing over 150 Patriots and taking upwards of 300 prisoners. Shortly after this victory, Tarleton was temporarily incapacitated by a violent fever, and his Legion performed significantly less well with his subordinates in command. Before he had made a full recovery, Tarleton was back in charge, resuming his hunt for Patriot militia forces. On 20 November 1780, Tarleton once again clashed with Sumter's militia at Blackstock's Farm. This time, Tarleton's Legion was outnumbered with only 270 men against Sumter's 1,000. Tarleton made it out of the skirmish unscathed and would falsely report a victory, although in truth his Legion had been badly mauled, suffering 60% casualties.

Blackstock's Farm, however, was only the first taste of a much more stinging defeat to come. In January 1781, Cornwallis sent Tarleton off to hunt down an American detachment under Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, which had been causing trouble for British military operations in South Carolina. With his trademark energy and relentlessness, Tarleton chased Morgan to a meadow called Hannah's Cowpens, where he found the Americans drawn up in a defensive line with their backs to the river; thirsting for blood and sensing an easy victory, Tarleton ordered his men to charge. But the colonel's recklessness finally caught up with him. Morgan had set a trap. His first line of men got off a musket volley, felling several of Tarleton's horsemen, before withdrawing, luring the mass of British dragoons toward a second American line. This line, too, fired before falling back, drawing the British in closer, until Tarleton's men were finally surrounded and enveloped by American militia and cavalry, which had previously been hidden. Tarleton's Legion, already tired from a dogged pursuit, was decimated at the Battle of Cowpens, which has sometimes been likened to a mini-Cannae. Tarleton himself barely escaped with his life, after a short cavalry duel with William Washington, cousin of the American general.

The battle was a major blow to Britain's hold on the South, with Tarleton's conduct drawing criticism from other British officers, who accused the 26-year-old colonel of lacking 'military maturity'. Eager to prove himself, Tarleton accompanied Cornwallis' army during its incursion into North Carolina, returning to form when he ambushed and scattered a detachment of American militia at Torrence's Tavern. At the Battle of Guilford Court House (15 March 1781), Tarleton lost two fingers on his right hand during a showdown with his American counterpart, 'Light-Horse' Henry Lee III. Guilford Court House was a pyrrhic victory for the British, prompting Cornwallis to march into Virginia, where he hoped to link up with another British army. In the final months of active warfare, Tarleton's Legion struck terror into the heartland of Virginia, conducting raids on countryside settlements as well as the capital of Richmond. Tarleton even raided Monticello in a failed attempt to kidnap Thomas Jefferson. Cornwallis' surrender at the Siege of Yorktown (28 September to 19 October 1781), however, brought an end to the fighting.

Postwar Life

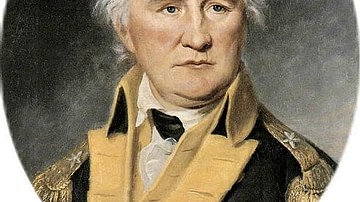

Tarleton, who had once again been wounded during the Yorktown campaign, was the only British officer not invited to dine with the Continental officers following the surrender. In 1782, he returned to England on parole, where he was greeted as a hero. Whereas many other British officers returned from the war with their reputations in tatters, Tarleton was cheered by the public and feted at court; the same exploits that had earned him infamy in America had won him glory at home. He became friends with the Prince of Wales, the future King George IV of Great Britain, and had his portrait done by Sir Joshua Reynolds, one of the leading artists in London. Reynolds' painting portrays Tarleton in the midst of battle, wearing the green jacket and plumed leather helmet that his Legion had made famous.

In 1787, Tarleton wrote an account of the war entitled History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781 in the Southern Provinces of North America, in which he defended his conduct both at Waxhaws and at Cowpens. The memoir may have helped Tarleton win election to the House of Commons in 1790. Representing Liverpool as a Whig, he was reelected continually until 1812. During his time in Parliament, Tarleton became an outspoken defender of the slave trade, an institution that many in Liverpool continued to profit from. Despite his opposition, Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act in 1807, banning the slave trade in the British Empire. He continued to serve in the military during his political career, rising to the rank of lieutenant general in 1801. During the Peninsular War (1807-1814) against Napoleonic France, Tarleton lobbied for command of the British Army, ultimately losing out to Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington.

Shortly after returning from the American Revolution, Tarleton seduced actress Mary Robinson as part of a bet; despite this unromantic beginning, their relationship ultimately lasted for 15 years. Robinson, who was a skilled writer, helped Tarleton with his political career, writing and editing many of his speeches. The couple never had any children, although Robinson did miscarry in 1783. The affair eventually ended, and Tarleton went on to marry Susan Bertie, the daughter of a duke, in 1798, although the marriage likewise proved childless. In his later years, Tarleton was made a baronet (1816) and created a Knight of the Grand Cross of the Order of Bath (1820). He died on 15 January 1833 in Herefordshire, at the age of 78.