Banpo Village is a Neolithic site in the Yellow River Valley, east of Xi'an, Shaanxi Province, in the People's Republic of China. The site was occupied from c. 4500-3750 BCE and covers almost 20 acres. Over 10,000 stone tools and artifacts, 250 tombs, six large kilns, storage pits, and almost 100 foundations of buildings have been excavated at the site.

Banpo is also referenced as Pan Po, especially by writers in the late 1950's CE. It was discovered in 1953 CE by workers hired to dig up the ground to build a factory. It was the first large-scale archaeological operation of the People's Republic of China and is one of the most significant Neolithic sites in the world. In the present day, it is one of China's best-known and most often visited tourist attractions.

Discovery & Name

In 1953 CE local workers were hired to dig the foundation for a factory that was to be built at the site. The name means `half slope' and comes from the area near the site. Historian Marilyn Shea writes that the village gets it name from the Banpo work group who uncovered it and how, "once the find was identified, the work group changed occupations and became diggers for the archaeologists. Eventually the dig was turned over to the Institute for Archaeological Research at the Chinese Academy of Science" (1). The original name of the village is not known. Excavations continued from 1953-1957 CE, and the Banpo Museum, located near the site, was opened in 1958 CE, displaying artifacts from the site and reconstructions of the homes and buildings. The Banpo Museum is the first of its kind in China featuring artifacts from a dig at the site of the excavations.

The Neolithic Village

Archaeologists have designated Banpo a type site, which means a representative model of a particular culture, in this case the Yangshao Culture, which flourished in the Yellow River Valley between 5000-3000 BCE. Banpo is a ditch-enclosed settlement that was surrounded by a moat. The homes were dug to three feet (1 meter) below ground level and the soil then used to fashion the foundations for the walls.

Walls were made of wood and topped by a thatch roof. Clay and wattle was then used to daub the walls for insulation, and the walls reinforced with fire-baked clay. Every building in the village was circular, and the village itself oval-shaped. The houses had hard-baked clay floors and front porches, which were shaded by the over-hanging roof of thatch. The cemetery was located outside of the village, beyond the moat, and so was the ceramics factory. The six kilns for firing ceramics at Banpo have all been found in one location outside the village, suggesting a kind of industrial complex there where communal pottery was shaped and fired. The inhabitants of Banpo did not use a potter's wheel but shaped every ceramic by hand.

The Culture

The Yangshao Culture was matrilineal, meaning that women were in charge and one's ancestry was traced through the mother's line, not the father's. Although western scholars have disputed this claim as some "Marxist invention," the physical evidence from Banpo speaks for itself: every female's grave that has been opened has more grave goods than the males; and no grave of the 250 discovered and excavated show any indication of a male chieftain but plenty of evidence for female leaders (based on the number of grave goods and the type). This points toward a matrilineal society in the strictest sense of women being in power and men subordinate.

Farming, Ceramics, & Clothing

The people of Banpo were hunter-gatherers who then shifted to an agrarian culture (farming). Farm implements like sickles and plows have been found on site. They ate primarily millet (cereals) and kept domesticated dogs and pigs. They were primarily vegetarian (like most Neolithic cultures) although there is evidence of occasional meat-eating from fishing and hunting.

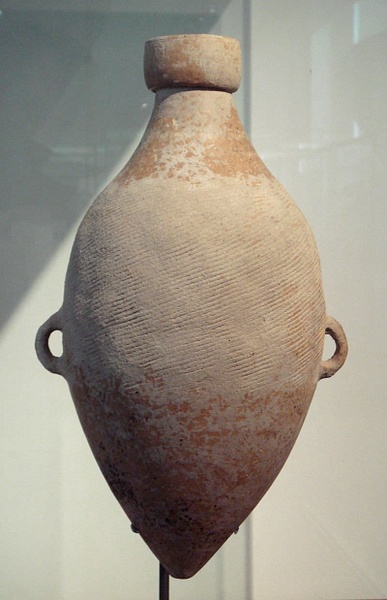

Their ceramics were highly developed, and one of the most interesting designs is the pointed amphora (also known as the "sharp-bottom water bottle"), which is an oval-shaped ceramic jug with a handle on each side, a thin, short, neck and a pointed bottom. The point at the bottom would seem impractical because the jug would tip over, but archaeologists believe the jugs were placed firmly in earth or soft clay and were more stable than flat-bottomed jugs, which could fall over more easily. The pottery was decorated with animal motifs, geometric designs, human faces (possibly deities) and dragons. The image of the Pig-Dragon (a figure with the face of a pig and body of a serpent), precursor to the now-famous Chinese dragon, appears on the ceramics excavated from Banpo.

There is evidence that the people of Banpo wore woven cloth garments. Such cloth has been found on human remains in graves and attached to artifacts. No evidence of ancient looms has been discovered, however. What these clothes may have looked like is unknown because of the state of decomposition of the cloth fragments.

Marriage & Childrearing

Women and men wore ornaments and jewelry but the females more than the males. Their marriages were arranged quite differently from the pattern most people recognize today. Archaeological evidence strongly suggests they practiced what the Chinese call zouhun - "free love" - which is sexual relations without commitment. Men would visit women's homes at night and sleep with them and then leave in the morning to return to their mother's house and work their mother's land.

Children were raised by the mother in her mother's house. This type of marital relationship is still practiced in China today by the Mosuo people (known as the Na to themselves) of the Yunnan and Sichuan provinces near Tibet. The Ah mi (elder female) is the head of the household and makes all of the important decisions. The evidence found in the homes at Banpo suggest the children were raised by their mothers in the same way the Mosuo people do today.

Writing

Banpo may have developed a system of writing long before the traditional date of the rise of literacy in China during the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BCE). Scratch marks on ceramic shards have been classified into 27 distinct categories, which suggest a form of communication and are not at all random. What the scratch marks may mean is unknown, and archaeologists do not even all agree that they are a form of written language.

Conclusion

Banpo Village was abandoned at some point c. 3750 BCE. No satisfactory reason has been found for the people leaving their homes. Evidence of ancient flood damage at the site is inconclusive because there is no way of knowing whether it happened before or after the people left. The village was abandoned quickly, however, and so a flood may have been the cause. Today the ancient village is one of the most visited sites in China after The Great Wall. Thousands of people every year - as many as 50,000 - make the trip and take the time to walk the ancient pathways of Banpo Village.