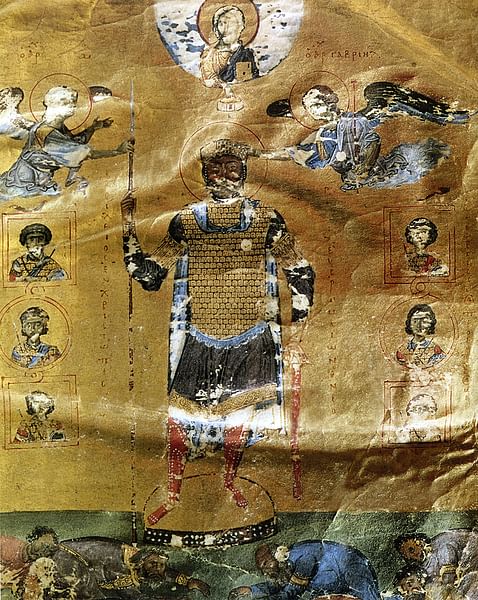

Basil II (aka Basilius II) was the emperor of the Byzantine Empire from 976 to 1025 CE. He became known as the Bulgar-Slayer (Bulgaroktonos) for his exploits in conquering ancient Bulgaria, sweet revenge for his infamous defeat at Trajan's Gate. With a tight hold on Byzantine purse strings and a private army of giant Vikings, Basil got the better of at least two significant usurpers for his throne, reconquered Greece and all of the Balkans, won victories in Syria and doubled the size of the empire. This colossus of Byzantine history is the subject of a biography in the Chronographia of the 11th-century CE Byzantine historian Michael Psellos.

Early Life

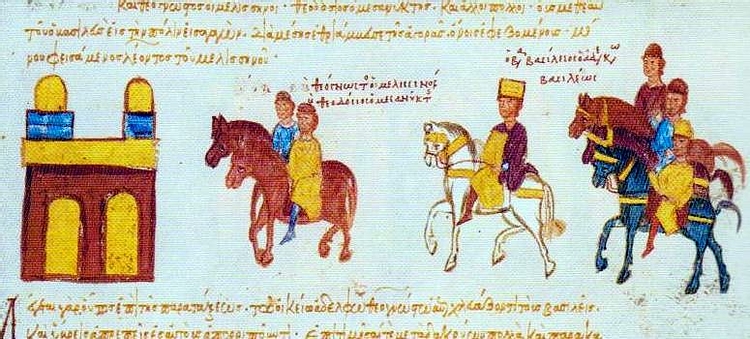

Basil, born in 958 CE, was the son of Emperor Romanos II of the Macedonian Dynasty, and when his father died, Basil, aged just five, and his younger brother Constantine jointly inherited the throne. The Empress Theophano, wife of Romanos, acted as their regent and married the general Nikephoros Phokas, who became Emperor Nikephoros II Phokas. It was not a happy marriage, and Theophano conspired to murder her husband in his bed in December 969 CE. The general John Tzimiskes then made himself emperor and banished Theophano to a monastery in the same year. John I Tzimiskes continued to act as guardian for the two young emperors and embarked on a series of successful campaigns in the Middle East. When Tzimiskes died of illness in 976 CE, Basil took his rightful place on the throne of the Byzantine Empire. At least on paper, Basil shared the role with his sibling Constantine, but it was very much Basil who ruled in practice.

The young Basil was not a particularly fine physical specimen, although he was skilful at riding a horse. He shunned fine living and was not much interested in literature; in many ways, he lived the life of an austere monk. Basil was certainly a pious man and was known to carry a statue of the Virgin in battle. These qualities, along with his dour nature, abruptness, and quick temper, combined with a complete lack of trust in anyone, unsurprisingly, did not foster much love and admiration from his subjects. There seemed to be a lack of the razzmatazz that one would expect from an emperor - no lavish parties, fine robes or flashy rings; even when he did wear the purple robes of his office, they were of a duller shade than they might have been. In warfare, too, Basil's campaigns, for all their success, were resolute rather than dashing, but his adroit skills of empire management would earn him respect from his people and fear from his enemies.

Domestic Policies

Basil's immediate problem on gaining the throne was to quash a rebellion led by the aristocrat Bardas Skleros, a general who was keen to continue in the privileged position he had enjoyed under previous emperors. Basil prevailed, despite some initial defeats to Skleros in Asia Minor, and was greatly helped by his namesake chief administrator, the gifted eunuch Basil Lecapenus, the parakoimomenos (emperor's chamberlain). Basil II then had to foil another coup, this time involving his disloyal and corrupt chamberlain, which attempted to make Bardas Phokas, an aristocratic clan leader, emperor. Basil the eunuch was exiled in 985 CE. The emperor was now ready to concentrate all his efforts on ruling alone and magnificently, not even marriage or family were allowed to distract him.

Basil sought to further consolidate his rule by reducing the ever-increasing power of the landed aristocracy and monasteries. Both these groups were expanding their landed interests at the expense of the poorer peasantry, either by purchase or conquest. More importantly for the state, the larger landowners often avoided tax or were simply given exemptions. Basil came up with the simple idea that the large landowners, or dynatoi as they were known, pay the tax arrears of the poor. The new tax plan, known as the allelengyon, met with robust opposition, was not successful and was abandoned by Romanos III in 1028 CE.

Another strategy to further centralise power was to permit payment instead of military service in the provinces, greatly reducing the manpower of local leaders. Basil could withstand the reduction in a wider military force because of his elite troops loaned to him by allied states and, rather cleverly, he used the new tax revenue to pay a new army more loyal to his own interests. This force would come in handy in the second half of his reign.

Military Campaigns

Basil's first and worst military expedition was in August 986 CE when he suffered a resounding loss to the forces of Samuel of Bulgaria (r. 976-1014 CE) in a narrow Bulgarian mountain pass known as Trajan's Gate. The emperor's army of 60,000 had already suffered an ignominious episode in their failed siege of the Bulgar capital Serdica (Sofia) but now it was wiped out, the colours lost, and Basil forced to flee back to Constantinople. The emperor would have to wait 28 years to gain his revenge, although when it came it would be total.

The consequences of the defeat at Trajan's Gate were the further expansion of Samuel's kingdom into Byzantine lands and the encouragement of two rebellions back home led by Bardas Skleros and Bardas Phokas (him again) respectively. Bardas Phokas even declared himself emperor in 987 CE. Basil, fortunately, could call on the help of Vladimir I of Kiev (r. 980-1015 CE), whose force of 6,000 Vikings bolstered his naval force and assured that the emperor restored order by 989 CE. The rebel army was routed, and three commanders were each given a uniquely tailored death: hanged, crucified, and impaled. There was a price for the assistance from Kiev, and it came in the form of Basil promising that his sister Anna would marry Vladimir, on condition that the latter agreed to be baptised. Both parties honoured their promise, useful as they were to each other as allies. The adoption of Christianity and its promotion by St Vladimir, as he would become, was a momentous action of long-lasting consequence for the Russian peoples.

There were other matters to attend to besides Samuel the Bulgar. Both Antioch and Aleppo in Syria had to be protected from Arab rule and especially the increasingly ambitious Fatimids. Basil himself led a victory in northern Syria in 995 CE when his army had arrived in super-quick time out of nowhere because Basil had issued each man with two mules, one for himself and one for his baggage. The emperor then settled on a long-term policy of hurting the Arabs in their pockets by restricting all trade with the caliph.

Basil's main focus, though, was the west and revenge on the Bulgars. His approach to warfare is here described by the historian J. J. Norwich:

Success for Basil depended on faultless organisation. The army must act as a single, perfectly coordinated body. When battle began, he forbade any soldier to break ranks. Heroics were punished with instant dismissal. His men complained about their master's endless inspections; but they gave him their trust because they knew that he never undertook an operation until he was certain of victory. (211)

The emperor was relentless, and after years of campaigns in both summer and winter, he won back Greece for Byzantium (997 CE), and then Pliska (1000 CE), Skopje (1004 CE) and Dyracchion (c. 1005 CE), amongst many other cities. In 1014 CE Basil finally won a great and decisive victory against the Bulgars at, appropriately enough, another mountain pass, this time at Kleidion in the Belasica Mountains. Over 15,000 of the enemy army were captured. The emperor, remembering his defeat to Samuel, carried the Byzantine tradition of mutilating the enemy to the extreme and blinded his captives, sending them back to their leader in groups of 100, each led by a one-eyed guide. Samuel was said to have died of a shock-induced stroke shortly after receiving this ominous sign of Basil's pitiless wrath.

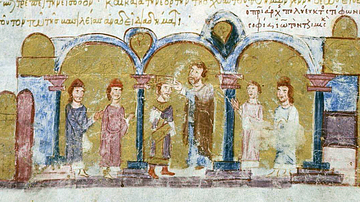

After some limited resistance led by Samuel's sons, ultimately, the Bulgar lands were incorporated into the blossoming Byzantine Empire, and Basil marched victorious into Serdica in 1018 CE. The unpleasant memory of Trajan's Gate was finally erased. Basil proved more generous with his new subjects than their army. He kept taxes low - allowing payment in kind instead of the usual gold, allowed certain provinces to remain under local, princely rule, gave certain nobles high office within the empire, and permitted the Bulgarian Church to remain independent from Constantinople with the only proviso that Basil select the archbishop.

Death

Basil kept on campaigning to the end, with more successful adventures in Georgian Iberia and Armenia in 1021-22 CE, where he captured Vaspurkan. His territories stretched even into Mesopotamia and were consolidated by dividing the conquered regions into new provinces of the empire. Italy, too, was reorganised, and a campaign was prepared to once more face the Arabs, this time in their last stronghold in the West, Sicily. Before these plans could come to fruition, though, Basil died on the 13th or 15th of December 1025 CE. He had almost doubled the empire which now "stretched from Crete to the Crimea, and from the Straits of Messina and the River Danube to the Araxes, Euphrates, and Orontes rivers" (Mango, 80) or, to put it another way, Byzantium was now "a superpower on two continents" (ibid, 176).

The emperor should have been buried in a splendid sarcophagus waiting for him alongside his predecessors in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, but Basil preferred a more simple tomb in a smaller church outside the city. His final resting place carried the following inscription:

From the day that the King of Heaven called upon me to become the Emperor, the great overlord of the world, no one saw my spear lie idle. I stayed alert throughout my life and protected the children of the New Rome, valiantly campaigning both in the West and at the outposts of the East…O, man, seeing now my tomb here, reward me for my campaigns with your prayers.

(Herrin, 219)

Legacy

Basil's near-50-year reign had ensured the Byzantine Empire was at its very zenith, as the historian E. R. A. Sewter here explains in his introduction to his translation of the emperor's biography by Psellus:

Basil had devoted all his energies to the business of ruling; he had never married, spent most of his time on or near the frontiers, developed a war-machine of terrifying efficiency, coveted autocracy, but despised its outward symbols. He crushed rebellions, subdued the feudal landowners, conquered the enemies of the Empire, notably in the Danubian provinces and the East. Everywhere the might of Roman arms was respected and feared. The treasury was overflowing with the accumulated plunder of Basil's campaigns. Even the lamp of learning, despite the emperor's known indifference, was burning still, if somewhat dimly. The lot of ordinary folk in Constantinople must have been pleasant enough. For most of them life was gay and colourful, and if the city's defensive fortifications were at some points in disrepair they had no cause to dread attacks. (12)

With Basil having no children, the title of emperor resorted back to his brother Constantine, who ruled as Constantine VIII from 1025 to 1028 CE, and his daughters Zoe and Theodora. Unfortunately, Basil's successors would squander their inheritance within a generation or two. The once-great empire's fortunes would wain, with none more tangible and symbolic an indicator than the ever-dwindling gold content of Byzantine coins. The 24-carat halcyon days of Basil II would, alas, never be repeated.