The Battle of Abritus was an engagement fought between the armies of Rome under the emperor Decius (249-251 CE) and a coalition of Goths under the leadership of Cniva (c. 250 - c. 270 CE) in 251 CE resulting in a victory for Cniva and the death of Decius and his son in a total defeat of the Roman army. The Romans had no choice afterwards but to allow Cniva to march out of Roman territory with all the booty and slaves he had captured on campaign.

The forces met in the valley of the Beli Lom River, near the town of Dryanovets, in modern-day Bulgaria. Cniva had already attacked the Roman cities of Novae and laid siege to Nicopolis ad Istrum, where he first met Decius, before the decisive battle at Abritus. Had Cniva capitalized on this victory and returned for another attack, he could have destroyed whatever forces Rome had left in the region to mount against him; he did not, however, and chose to take his substantial booty home to fight against Rome another day.

He has been identified with the Goth leader Cannabaudes who was defeated by Aurelian (270-275 CE) in 270 CE and was killed, along with 5,000 of his troops. Whether Cannabaudes was the same king as the victor of Abritus is disputed, but there is no doubt that Cniva's victory in 251 CE was a severe blow to Rome and the first time a sitting emperor – as well as his son and successor – was killed in battle.

The Crisis of the Third Century & the Goth Invasion

At the time of the battle, Rome was going through the turmoil known as the Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE) which began when the emperor Alexander Severus (222-235 CE) was assassinated by his own troops while campaigning in Germania. Severus decided to follow his mother's advice and pay his German adversaries off instead of meeting them in battle, and this was seen as dishonorable and cowardly by his commanders who then removed him in favor of the Thracian Maximinus Thrax (235-238 CE). This paradigm then became standard operation; if an emperor proved disappointing, he was killed and replaced with a more promising candidate.

Maximinus Thrax was assassinated by his troops in favor of the young emperor Gordian III (238-244 CE) who was then killed by his successor Philip the Arab (244-249 CE) who was then disposed of by Decius. Decius came to power following Philip the Arab's unpromising campaigns against Shapur I (240-270 CE) of the Sasanian Empire and Shapur I and his son Hormizd I (270 - c. 273 CE) had again mobilized their armies to strike at Roman holdings in Mesopotamia. At the same time, there were domestic issues to be handled in Rome and a plague which was stalking the citizenry as well as numerous other problems Decius had to focus on.

In addition to these challenges, Decius considered the new faith of Christianity a threat to Rome's stability and inaugurated a series of persecutions of the sect. Anyone suspected of being a Christian was forced to perform a single sacrifice to the traditional gods of Rome; if they did, they were issued a Certificate of Sacrifice stating the ceremony had been carried out and witnessed, and if they did not, they were executed. Although this policy seems to have been popular among many Romans (Decius was lauded as “Restorer of the Cults”), it obviously was not among the Christian population and, further, diverted time and energy to religious persecution which could have been better directed to the other far more pressing issues.

In the middle of Rome's chaos, and with a new emperor in power trying to contain it, Cniva of the Goths and his coalition marched into Roman territory in 250 CE to pillage, kill, and enslave as many as he could. His army was comprised of a number of different tribes, not just his Goths, and among them were the Carpi, Bastarnae, Taifali, and Vandals. His first strike was against the border city of Novae but he was driven back by the general (and future emperor) Gallus (251-253 CE). Cniva avoided another encounter with Gallus and moved to lay siege to the city of Nicopolis ad Istrum while his Carpi contingent attempted to take the city of Marcianopolis. Both of these cities repelled the attacks, and Decius arrived with his army to relieve the siege of Nicopolis.

Philipopolis

Decius had been in the region since 249 CE when he had been a commander before he deposed Philip and took over as emperor. Since Philip's assassination, Decius had been on the move trying to contain or prevent invasions into Roman territories. Philip had stopped the payments to the Goths, Sassanid Persians, and various other tribes, all instated by Maximinus Thrax, which had kept them from open hostilities, and now there were threats against Rome from all sides. The most pressing at the moment, however, was Cniva and so Decius directed his forces against the Goths.

He drove Cniva's forces from Nicopolis but did not defeat him, and Cniva was able to leave the field with his army intact. Cniva led his forces north, ravaging the country as he went, followed ineffectually by Decius. In the north, near the city of Augusta Traiana, Decius paused in his pursuit to rest his army, and this was just the opportunity Cniva seemed to be waiting for. The Romans were attacked without warning by Cniva's forces and scattered. They had been taken completely by surprise and Cniva was able to inflict heavy casualties while sustaining few of his own. Decius and his commanders fled the field with what remained of the army and regrouped while Cniva gathered the weapons and supplies they had left on the field and then marched again south toward the city of Philipopolis.

He lay siege to the city in late spring 250 CE while Decius' forces were still scattered and the emperor was trying to reform his army. Philipopolis was garrisoned by a Thracian force under the command of Titus Julius Priscus which was far too small to defeat the much larger force of the Goths and their confederates outside the walls. The Thracians declared Priscus emperor, perhaps to empower him to legally negotiate with the Goths, and he brokered a deal by which the city and its people would be spared if they surrendered without resistance. Once the gates were open, however, the Goths ignored the agreement, and the city was sacked and burned. Priscus was either killed or captured at this time; there is no further record of him.

The Battle of Abritus

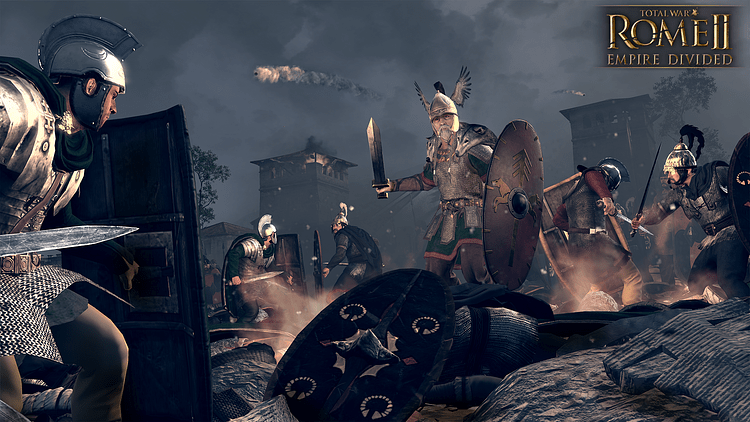

Cniva looted the city and took thousands of citizens captive. Having gotten what he came for, he then turned his forces around and headed back for his homeland, the long train of prisoners and future slaves winding out behind his army. Decius, meanwhile, was still recovering his forces and trying to mobilize them as an effective army. Once finally organized and regrouped, the Roman forces again pursued Cniva's army as it moved north toward the border. Cniva, hearing of the pursuit, halted his retreat and took up a position in a marshy area in a river valley near the city of Abritus, a region he seems to have known well.![Battle of Abritus [Artist's Impression]](https://www.worldhistory.org/img/r/p/750x750/7761.jpg?v=1599498902)

When the Romans charged, the Goths fell back, broke ranks, and took flight through the swamp. The Romans interpreted this as a rout and followed them, confident of victory. The swamp, however, completely nullified any advantage of the Roman formations which soon fell apart as they pursued the fleeing Goths. The Roman soldiers found themselves trapped in the thick, muddy water, unable to advance in unison, and then Cniva unleashed his attack from three sides. Decius and his son were both killed, and the rest of the army almost annihilated.

Decius' commander Gallus was now proclaimed emperor and led what was left of the army out of the swamp in retreat. Cniva and his army took the booty from Philipopolis and resumed their march back home. Gallus has been criticized since shortly after the battle for not pursuing the Goths and rescuing the captives but, as scholar Herwig Wolfram points out, he was given few options:

[Gallus] had to allow the Goths to move on with their rich human and material spoils and even had to promise them annual payments. This is why he is charged to this day with treason and incompetence. But in fact, his actions were forced upon him by circumstances. After the defeats at Beroea and Philippopolis, and especially after the catastrophe at Abritus, the new emperor had no other choice. He had to get rid of the Goths as quickly as possible. (46)

Conclusion

The story of the Battle of Abritus is first told by the Greek historian Dexippus (210-273 CE) and is the only account extant by a contemporary of the event. Dexippus and later Christian writers would call attention to Decius' persecution of the Christians as the reason for his defeat and death. According to this view, the Christian God was avenging the deaths of his followers at Abritus. These claims aside, a simpler explanation is that Cniva knew the terrain and was a better military leader than Decius and so won the battle without the need for any supernatural ally.

The site of the battle was disputed for centuries until 2014-2016 CE when archaeologists positively identified the site through finds of Roman and Goth artifacts discovered near the modern-day city of Razgrad and the town of Dryanovets in the valley of the river Beli Lom. The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 325 - c. 400 CE) describes how Decius was lured into the trap at Abritus by the Goths and his description matches the terrain outside of Razgrad as well as that given by Dexippus.

The Battle of Abritus was not a decisive turning point in Rome's history but was a telling blow against the former might of the empire. In the past, except for a few extraordinary cases, the Roman army led by their emperor was usually victorious and was recognized as a formidable fighting force. At the Battle of Abritus, however, the army, under the experienced leadership of Decius, was destroyed and the emperor and his successor killed in an engagement which the Romans had every reason to believe should have gone the other way.

It would be events such as Abritus which would lead Latin writers to conclude that the city – and, by extension, the empire – had been deserted by the traditional gods who were upset by the new religion of Christianity and would lead later writers such as Orosius (5th century CE) to write defenses against this claim. Whether the rise of Christianity contributed to the fall of the Roman Empire has long been debated, but that question aside, the empire was already in turmoil and crumbling, and the Battle of Abritus stands as a telling example of the kinds of problems which beset Rome during the Crisis of the Third Century.

Emperors were no longer masters of the realm who could dictate sound policy as they saw fit; they were now at the mercy of the military who could kill and replace them if they seemed weak or ineffective. Whatever may have gone through Decius' mind in choosing to launch his attack on Cniva at Abritus, he must have been aware that, if he did not, he ran the risk of assassination by his own troops.

This model of leadership, as noted, was standard throughout the era of the Crisis of the Third Century and even though it was rectified under the reign of Diocletian (284-305 CE), Rome would never be the same power it had once been following the events of the 3rd century CE. A different Rome would emerge afterwards, which would face further difficulties in a new incarnation as the Eastern and Western empires until its eventual fall.