The Battle of Chaeronea took place in 338 BCE on an early August morning outside the town of Chaeronea. Although for centuries the cities of Athens and Sparta dominated Greece, politically, militarily and economically, the Battle of Chaeronea, one of the most renowned of all Greek battles, only involved one of these cities: Athens combined forces with Thebes to meet the rising power of Macedon in a fight that would change history.

Since the time of Homer, the concept of arête and its emphasis on strength and courage symbolized the Greeks in battle. However, in the 4th century BCE a new threat appeared to challenge the dominance of the city-states to the south when Macedon, previously viewed as a land of barbarians, came under the shrewd leadership of Philip II, a man who would completely reshape the Macedonian army. He would prove this new military might at the Battle of Chaeronea; the Macedonian victory at Chaeronea would put Greece into what historian G. Maclean Rogers describes as a 'deep sleep', both politically and militarily. It would never again regain its supremacy in the Mediterranean.

Philip II Rebuilds the Macedonian Army

Philip had inherited a country that was militarily weak. Recognizing this weakness, he rebuilt its fragile army into a strong, fighting machine. This new army was based on the celebrated Sacred Band of Thebes (the elite fighting force of the Theban army) and their equally efficient wedge, a concept that Philip had learned while a captive in Thebes in 367 BCE. Philip II's new army was no longer an army of citizen-soldiers but one of professionals. He reorganized the old, traditional phalanx and replaced the outdated hoplite spear with the sarissa, an 18- to 20-foot pike, adding a smaller double-edged sword or xiphos. Finally, he redesigned the antiquated shield and helmet. It did not take long for him to reveal to the rest of Greece the might of the Macedonian army, attacking and defeating the Thracians to the north, proving to the people of Athens that Philip was a viable threat.

Athens & Thebes Join Forces

Between 352 and 338 BCE, Athens and Philip would remain at odds. Despite an uneasy peace with Macedon - a peace signed after the Social Wars that was uneasy because Philip offered Athens his help, then took control of cities that he wanted for himself after he had offered them to Athens - Athens could only sit silently, remaining apprehensive about these barbarians to the north. The Athenians were reluctant to fight them alone as they were unable to secure any alliances, and quite honestly, they did not have the finances. And added to this, Philip's military successes garnered him a seat on the Amphicroyonic Council (an association of Greek city-states) which was a further insult to the Athenians.

Although Athens saw Philip as a menace, others viewed him as someone who could unite all of Greece. Meanwhile, Philip increased his hold on Greece by capturing the cities of Crenides in 356 BCE, a city he renamed Philippi; Methone in 354 BCE; and finally in 348 BCE, Olynthus on the Chalcidice peninsula. These brutal attacks affected Athens when he seized grain shipments headed for the city. These assaults on their food supply caused Athens to seek an ally, eventually turning to their neighbors to the north, Thebes. Although long considered enemies, the two cities now had a common foe: Philip. Athens reminded Thebes that because of their location, Thebes would fall before Athens. Thebes, however, already understood the dangers of Philip, and they looked not south to Athens as an ally but eastward to the Persians, whose dislike for the Macedonian king stemmed from his presence along the northwest coast of Persian-controlled Anatolia.

By 339 BCE, it was apparent that a final decisive battle against Philip could not be avoided. One angry Athenian who truly understood this danger to Athens, as well as to the rest of Greece, was Demosthenes. The gifted orator spoke of this threat in a fiery series of speeches called the “Philippics.” It was he who realized the need for securing an ally, namely Thebes. Demosthenes believed the new cities should put aside their differences and fight as one against the Macedonian barbarians. Since many within the Athenian government opposed going to war against Philip, the crafty Demosthenes flattered them by reminding them of their victory against the Persian Empire at the Battle of Marathon. They could easily defeat this barbarian to the north, he claimed. Reluctantly, the Athenians conceded to Demosthenes' wishes.

Preliminaries

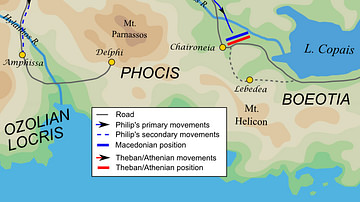

Initiating their first line of defense, the Athenian army marched to Boeotia, where they placed men at the most strategic mountain passes (especially at the Gravia Pass north of Amphissa and Parapotamii on the road to Thebes) in an attempt to block Macedonian access to the Gulf of Corinth, which was a source of much-needed supplies; the lack of supplies forced Philip to retreat. These mountain passes remained guarded throughout 339 and into 338 BCE and both Athens and Thebes felt safe, until many of those guarding the passes began to grow restless and, further, natural animosity was beginning to cause serious problems.

Added to this disparity was a rumor, spread by Philip himself, that the Macedonians were about to withdraw. When Philip withdrew his troops from Cytinium, Greek forces at Amphissa relaxed their guard. Seeing this, Philip immediately seized the opportunity and attacked at night, destroying the defenders of the pass and occupying the city. He then moved further west, capturing the city of Naupaetus. When Philip offered peace, Demosthenes boldly convinced both Athens and Thebes to refuse. War was now unavoidable. The king and his young son Alexander overran the city of Elateia on the Boeotian border; the route to Athens and Thebes was now open. Philip marched his troops southward to confront the enemy on a small plain outside the town of Chaeronea.

The Battle Begins

The Athenians, Thebans, and a small number of allies positioned themselves, with the Athenians (10,000 infantry and 600 cavalry) on the left, allies in the center, and the Thebans with 800 cavalry and 12,000 infantry (including the 300 members of the Sacred Band) on the far right. Across from Athenians were the Macedonians, with Philip on the far right, totalling 30,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. Facing the Thebans was the 18-year-old Alexander with the Companion Cavalry. Plutarch, in his Life of Alexander, would write of the young commander's courage, “… he is said to have been the first man that charged the Theban's sacred band…This bravery made Philip so fond of him, that nothing pleased him more than to hear his subjects call himself their general and Alexander their king.” Whether or not Philip actually felt this way or it is simply Plutarch's perception or opinion is unknown.

Though not professional soldiers like their Macedonian counterparts, the Athenians took the initiative and attacked first. In a suspicious move, Philip pulled his men backwards, drawing the unsuspecting Athenians in. Quickly, Philip charged into the Athenian center and then veered left, breaking through the enemy line. Seeing defeat imminent, the allies fled. On the Macedonian left, Alexander advanced into the gap left behind by the charging Athenian troops. He was able to surround the Sacred Band, crushing them completely. The remaining Athenians panicked, Demosthenes included, and escaped. When 1,000 Athenians were killed, Philip saw to the burial of the dead and sold the remaining captured troops into slavery.

About the battle, the historian Diodorus wrote,

… they were equal indeed in courage and personal valor, but in numbers and military experience a great advantage lay with the king … About sunrise the two armies arrayed themselves for battle. The king ordered his son Alexander … to lead one wing, though joined to him were some of the best of his generals. Philip himself … led the other wing …. The Athenians drew up their army, leaving one part to the Boeotians, and leading the rest themselves. … the battle was fierce and bloody. It continued long with fearful slaughter, but victory was uncertain, until Alexander, anxious to give his father proof of his valor … was the first to break through the main body of the enemy, directly opposing him, slaying many; and bore down all before him — and his men, pressing on closely, cut to pieces the lines of the enemy; and after the ground had been piled with the dead, put the wing resisting him in flight. The king, too, at the head of his corps, fought with no less boldness and fury, that the glory of victory might not be attributed to his son. He forced the enemy resisting him also to give ground, and at length completely routed them …. (Library of History, Bk. XVI, Ch. 14)

The Aftermath

After the battle, Athens was forced into an alliance, while Thebes lost rich agricultural lands in Boeotia. The Athenians may have fought bravely, but the Battle of Chaeronea is viewed by many to be a turning point in history, after which the Greeks were no longer a military or political threat. Philip now turned his military ambitions away from Greece and looked eastward to Persia. Unfortunately, his untimely assassination would leave this achievement to his son, Alexander, who would become known as Alexander the Great.