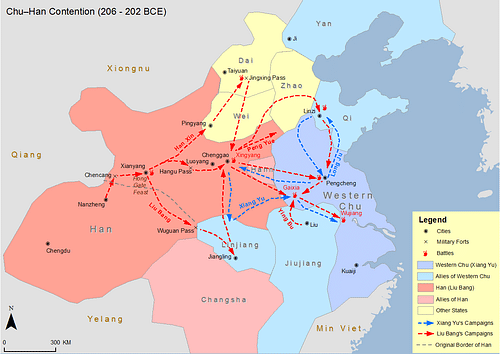

The Battle of Gaixia (202 BCE, also known as Kai-Hsia) was the decisive engagement of the Chu-Han Contention (206-202 BCE) at which Liu Bang (l. c. 256-195 BCE), from the State of Han, defeated Xiang Yu (l. 232-202 BCE) of the State of Chu and subsequently founded the Han Dynasty.

The battle, which took place in a canyon on the Central Plains of China, was the culmination of four years of brutal civil war which had broken out following the collapse of the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BCE). Xiang Yu and Liu Bang fought together against the Qin forces shortly after 210 BCE when Shi Huangdi (r. 221-210 BCE), the first emperor of the Qin, died and Qin control of the country loosened. After the fall of the Qin capital of Xianyang in 206 BCE, however, conflicts of interest made Xiang Yu and Liu Bang enemies and they turned on each other.

Liu Bang was finally victorious when his general Han Xin kidnapped Xiang Yu's beloved consort, Lady Yu (also known as Yuji and Consort Yu) and lured Xiang Yu to Gaixia to rescue her. After defeating Xiang Yu, Liu Bang took the name Gaozu as first emperor and founder of the Han Dynasty (202 BCE-220 CE). The Battle of Gaixia (pronounced `Kai-SHE-uh') is therefore understood as the pivotal engagement in the transition from the Qin to the Han Dynasty.

Rise of the Qin Dynasty

When the era of the Zhou Dynasty ended (during the Spring and Autumn Period, c. 772-476 BCE) China, which had never been fully unified, split into seven separate states – Chu, Han, Qi, Qin, Wei, Yan, and Zhao, each an independent political entity – who then fought each other for control in what has come to be known as the Warring States Period (c. 481-221 BCE). Shi Huangdi of the State of Qin ignored the previous rules of engagement in military matters, which emphasized civility, and instead waged total war in subduing the other states. Once he had defeated and unified them, he continued the same brutal policies which had brought him to power.

Shi Huangdi ruled his vast kingdom through fear as his spies and secret police network ensured that no one felt safe in objecting to any of his policies. Any books which did not support his philosophy of Legalism or focus on him or his family were burned and those who objected were killed.

He conscripted thousands for work on his northern border wall (which followed the same course as the later Great Wall of China) and the Grand Canal as slave laborers while others served in his armies. As long as Shi Huangdi was in power, there was no chance of any organized revolt because his spy network was so vast and so efficient.

The Early Alliance

In 210 BCE, however, the emperor died on a trip while seeking an elixir of immortality and his son, Qin Er Shi, took the throne. Qin Er Shi was ill-equipped to follow his father and the government's tight control of the people loosed as he repeatedly failed at every aspect of rule; he was assassinated after three years. His nephew, equally inept, then took the throne but could do nothing to hold back the rising tide of rebellion by the former subject states.

Between 210-206 BCE, these states battled the Qin (and often each other) for supremacy. By 206 BCE, the Chu and Han were the strongest states and the generals of their respective armies were the recognized leaders of the revolt: Xiang Yu of Chu and Liu Bang of Han. These two were equally skilled commanders and each had contributed significantly to the defeat of the Qin forces. Xiang Yu had fought in more engagements while Liu Bang was responsible for the final victory at Xianyang. Scholar Harold M. Tanner writes:

Theoretically speaking, Liu Bang and Xiang Yu were both fighting on behalf of King Huai of Chu. In fact, they were competitors for power. Each man wanted to be the first to break through the passes into the Wei Valley and take the Qin capital of Xianyang. Liu Bang got there first. According to the histories (written during the Han, and thus biased against Xiang Yu), Liu Bang treated the people and the pitiful third ruler of Qin with kindness and courtesy. When Xiang Yu arrived with a much larger army, he was livid with anger. Liu Bang survived only by apologizing and turning the Qin capital and the Wei Valley over to Xiang Yu. (93)

Xiang Yu was of noble birth and had taken the title 'King of Western Chu' after assuming command of the troops. Liu Bang was a commoner (though some sources cite him as a prince) but was raised to noble status by Xiang Yu who conferred upon him the title King of Han, with all attendant power, after he had apologized and handed over Xianyang. Tanner describes the differences in the two men:

Xiang Yu and Liu Bang came from very different backgrounds. Many generations of the Xiang family had served the state of Chu as generals. Xiang Yu was a big, powerful aristocrat, trained in the art of war. Liu Bang was a poor, low-ranking official, a village headman, with a fondness for drink and women. As village headman, Liu Bang was once assigned to take a group of men for forced labor on the First Emperor's tomb. So many men escaped en route that Liu Bang gave up, let the rest go as well, and fled into the swamps, where some of the men joined him. (92)

Liu Bang, then, was hardly fit for the position of supreme leader of the troops and had fewer men under him than Xiang Yu. Even though the victory at Xianyang had been Liu Bang's, Xiang Yu, claiming victor's rights and the superior social status, set about the redistribution of land. In administering the re-ordering of the states, he gave away lands which Liu Bang claimed belonged to him. When Liu Bang contested this decision he was ignored and, feeling dishonored by his former ally, he rallied his forces and attacked Xiang Yu.

The Chu-Han Contention

Between 206 and 202 BCE, the forces of the Han and the Chu battled each other with the additional states allying themselves now with one and now with the other. Shi Huangdi had conquered the states by ignoring the old rules of chivalry concerning warfare and conducting a programme of total war; this lesson was not lost on either Liu Bang or Xiang Yu. The Chu-Han Contention claimed thousands of lives and destroyed vast areas of farmland as well as urban areas.

Battles between the Han and the Chu forces raged until 203 BCE when Xiang Yu negotiated a peace known as the Treaty of Hong Gate (also known as the Treaty of Hong Canal). Under the terms of the accord, China would be divided between the Han and the Chu. Liu Bang signed the treaty but desired the same unification, and attendant glory, which Shi Huangdi had achieved and, breaking the agreement, resumed hostilities.

Xiang Yu drove Liu Bang back behind the defenses of Han and besieged the central fortification. Liu Bang then orchestrated a three-pronged attack on Western Chu through the combined forces of the generals Han Xin, the king of Qi, and Peng Yue of the province of Liang. Xiang Yu was forced to drop the siege to defend his homeland. Liu Bang, however, had ordered Han Xin to circle back and harass the Chu forces during their march.

Han Xin did far more than that and successfully ambushed Xiang Yu and his army repeatedly. Han Xin's goal, however, was not to engage his opponent directly in any prolonged battle but to maneuver Xiang Yu into a hopeless position. Han Xin continued his tactics in order to manipulate the large Chu force into the canyon at Gaixia on the Central Plains of China where their numbers would work against them and they could be destroyed.

The Battle at Gaixia

Xiang Yu's young concubine, the Lady Yu (born Yu Miaoyi), who always travelled with him on campaign, was captured during one of these skirmishes and Han Xin quickly conveyed her to Gaixia. He positioned his captive, and the bulk of his troops, deep in the canyon but situated other groups of warriors along the route. Xiang Yu, knowing he was walking into a trap, mobilized his forces to save the woman he loved. He sent most of his army on toward his capital at Pengcheng and, with 100,000 warriors, marched for Gaixia.

Once Xiang Yu's forces had fully entered the canyon, Han Xin deployed his troops in the “ambush from ten sides” and destroyed the army. Xiang Yu and his remaining forces fought on until nightfall, finally rescuing Lady Yu. In the darkness then, Liu Bang and Han Xin ordered their men and the captured enemy soldiers to sing the native songs of Chu. These songs reminded the remaining Chu forces of their homes and their families and further demoralized the army. Men began deserting in the darkness and headed for their homes.

Xiang Yu rose to stop the deserters by force but, at the request of Lady Yu, relented and those who wished to were allowed to leave. He then sat drinking with Lady Yu and is said to have composed the lament The Song of Gaixia (which is still sung today). Listening to the songs of his native land sung by the enemy throughout the night, Xiang Yu believed that Western Chu must have fallen to the Han and his cause was lost. With Lady Yu, he sang his lament and, according to the historian Sima Qian (145-86 BCE), alternated verses with her which is how the song is often sung in the modern day.

Lady Yu performed the sword dance as she sang her verses and then, blaming herself for the Chu defeat, and wishing to save Xiang Yu from further disaster through his love for her, she killed herself with his sword. Though surrounded by enemy forces, with his troops steadily deserting him, Xiang Yu ignored the pleas of his counselors to move on and buried Lady Yu, erecting a large mound over her grave to prevent desecration.

By morning, Xiang Yu had fewer than 800 men under his command but, with these smaller numbers, he was able to maneuver more easily and fought his way back out of the canyon of Gaixia. He headed directly for Pengcheng, the Han forces following quickly at his heels, and reached the Wu River where they caught up with him. A fierce battle ensued in which most of the Chu forces were slaughtered. Xiang Yu fought to the end and, when he understood he would soon be captured, committed suicide by slitting his own throat with his sword. He was 30 years old.

Liu Bang's Victory & the Rise of the Han

Liu Bang then proclaimed himself emperor, founding the Han Dynasty which would rule China from 202 BCE to 220 CE. He was known as the Emperor Gaozu and governed with his wife, the Empress Lu Zhi. In time, he became suspicious of his old allies Peng Yue and Han Xin and had them both executed, under the pretext of spreading sedition, in 196 BCE. To divert blame from himself, he had the order come from Lu Zhi. With no other model to follow and no experience in government, the new emperor Gaozu modeled his dynasty after the Qin whom he had helped overthrow; although he administered his laws in a far-gentler fashion.

The Battle of Gaixia is among the most famous in Chinese history and the merits of the two antagonists, as well as their faults, are still debated. The story of Xiang Yu and his consort Lady Yu is the subject of the 1993 novel Farewell My Concubine by Lilian Lee, and the 1993 film by Chen Kaige of the same name, and has also been adapted as a popular opera. In 2011 the film Hong Men Yan, directed by Daniel Lee, was released (referencing the Feast of Hong Gate) based on the Chu-Han Contention and the Battle of Gaixia (the film's title in English is White Vengeance which has nothing to do with the Chinese title).

Another feature film, The Last Supper, written and directed by Chuan Lu, was released in 2012, depicting the battle and the story of Xiang Yu and Lady Yu. The Tomb of the Concubine, Consort Yu's grave, is a highly regarded tourist attraction nine miles (15 km) east of modern Suzhou City in Lingbi County. The Chinese phrase, “surrounded by Chu songs” is derived from the Battle of Gaixia and refers to anyone in a hopeless situation.

The story of the Chu-Han Contention has always been colored by the bias of the Han Dynasty scribes who first recorded it and cast Xiang Yu as the tyrannical villain opposite the noble Liu Bang. Modern scholarship, however, has reevaluated these early accounts and Xiang Yu is regarded today, for the most part, as a great general whose defeat was only possible because of his devotion to the Lady Yu.