The Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE gave Thebes a decisive victory over Sparta and established Thebes as the most powerful city-state in Greece. The victory was achieved through the daring and brilliant pre-meditated tactics of the Theban general Epaminondas who smashed the Spartan hoplites and put to rest the myth of invincibility that Sparta had enjoyed for centuries.

The exact details of the battle, which took place on the plain of Leuctra near Thebes, and even its full consequences are debated amongst scholars, notwithstanding the fact that the earliest source is Xenophon who could draw on eyewitnesses for his account of the battle in his Hellenika.

Historical Context

In the early 4th century BCE the Greek poleis or city-states, following a century of mutually damaging on-off conflicts, had established an uneasy peace but as Sparta called for the Boeotian Confederacy led by Thebes to be abolished, war seemed once again on the horizon. Thebes quite naturally rejected the Spartan demands, a reaction not unexpected as is evidenced by the fact that Sparta had already mobilised their army and taken a position on the western border of Boeotia before the Thebans gave their answer.

The Assembled Armies

Sparta and its allies were led by King Cleombrotus. The army consisted of four divisions (morai) numbering 2,048 men of which 700 were full Spartan citizen hoplites. Added to these were some 9,000 men provided by Sparta's allies. Of this 11,000 total, 1,000 were cavalry. It might also be noted that after more than a decade of fighting, the Spartan's allies probably lacked enthusiasm for further conflicts.

Thebes had at its disposal some 7,000 hoplites which included the 300 members of the elite Sacred Band, a unit of homoerotic pairs who swore to defend their lovers to the death and who at Leuctra were led by the gifted and charismatic Pelopidas. The Thebans also had 600 cavalry who were probably the best in Greece at that time. In addition, there was a small force of light-infantry (hamippoi) who were armed with javelins and supported the cavalry. The entire force was led by the brilliant general Epaminondas. The austere military commander, a student of Pythagorean theory, would prove to be the most innovative and successful commander Thebes had ever had and one of Greece's finest ever generals.

Preliminaries

Some of the Theban commanders at first thought it prudent to retreat behind the walls of Thebes and invite a siege rather than face the fearsome Spartans on the open battlefield. However, Epaminondas persuaded them otherwise. Always able to use propaganda and imagery to boost morale, Epaminondas recalled the notorious rape of two local virgins by two Spartans at Leuctra. The two victims had committed suicide in shame, and a monument in their memory had been set up. Epaminondas made sure suitable homage was paid to this monument before the battle and another symbolic gesture he was credited with was the brandishing of a snake and his statement that by striking the head of the snake - the Spartan army - the whole snake would die - Spartan dominance of Greece.

The first real action of the battle was when the Spartans attacked the Theban non-combatants (baggage porters, merchants, etc.) who were retreating back to Thebes. However, in the attack, Hieron, the Spartan leader was killed and the Thebans were forced to rejoin the main force.

Battle

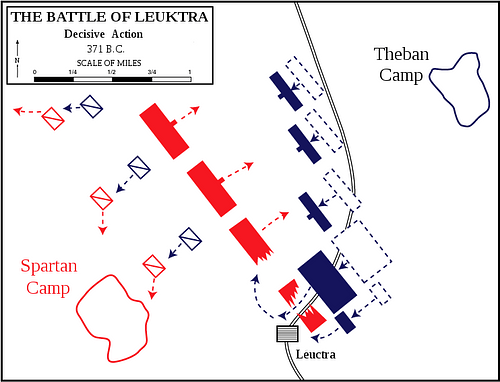

Cleombrotus positioned his troops in the traditional phalanx formation of heavily armoured hoplites 12 men deep with two wings. Cleombrotus himself, surrounded by his elite hippeis (300-man bodyguard), took up position on the left side of the right wing.

Epaminondas was much more innovative and put his cavalry and light-infantry in front of his own phalanx formation. Rejecting the convention of making one's right wing the strongest, he made his left wing extraordinarily deep - 50 ranks of men - and made his lines narrower than the Spartans. The Sacred Band was also positioned on the left wing with the Boeotian allies being stationed on the right wing, 8-12 men deep.

Cleombrotus responded to this surprising development by reorganising his own lines, moving his cavalry out front and extending his line in an effort to outflank Epaminondas' left wing. This relatively complex series of battle manoeuvres exposed Cleombrotus' immediate left side, and as the Spartan cavalry were no match for the Thebans who soon routed them, the Spartan horsemen were forced back onto their own lines and through the gap which had opened on Cleombrotus' left. The Thebans followed them through this gap and proceeded to create chaos in the Spartan formation. Epaminondas, meanwhile, attacked at an angle towards the left so that, in effect, Cleombrotus was being pushed away from his own line. Epaminondas' attack was also conducted with his own right wing slightly in arrears in an echelon formation to protect his own exposed flank as he attacked the Spartan hippeis. At this point, Pelopidas and the Sacred Band also attacked Cleombrotus' position resulting in the fatal wounding of the Spartan king and the complete defeat of the Spartan right.

In all, 1000 Lacedaemonians fell, including 400 Spartan hoplites. Thebes was now the most powerful polis in Greece and, after 200 years of victories on land, the myth of Sparta's military invincibility was finally smashed.

The strategies that Epaminondas had employed in the battle were not entirely new, but in the past they had been used more out of necessity rather than planning, and no one had ever combined them to create such a winning formula. The massively strengthened left wing, the use of cavalry in front of the hoplite lines, attacking at an angle, employing an echelon formation, and going for a direct frontal attack on the opposing commander's position were, collectively, the most innovative and devastating pre-meditated military strategy ever seen in Greek warfare and the defeat of mighty Sparta shocked the Greek world.

Aftermath

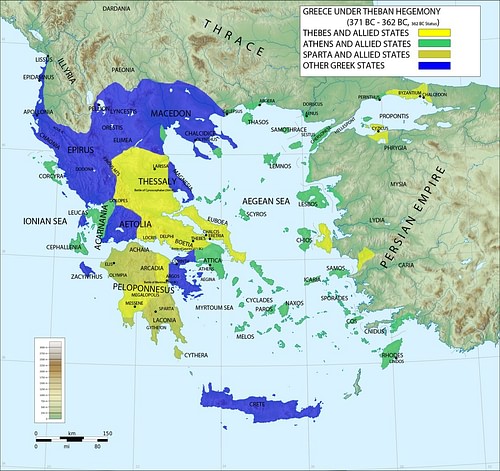

Sparta's defeat led to the disintegration of the Peloponnesian League, as many of her allies became independent or switched allegiance to Thebes. The Messenian helots were freed, a new polis of Messene was established, Mantineia, which had suffered a demise under Spartan control, was revitalised into a thriving polis once again, and another new polis - Megale Polis (Megalopolis) - was founded in Arcadia to keep Sparta in check.

Following the battle and the complete upheaval of the status quo in Greece, Athens called for a peace conference in 371 BCE but Thebes refused, perpetuating the power struggle between various Greek poleis which had bedevilled Greece for the last century or more. Athens even sided with her old enemy Sparta, but Thebes, with Persian backing, continued her expansionist policies and, once again led by Epaminondas, went on to defeat the Spartan and Athenian alliance at the battle of Mantineia in 362 BCE. However, Epaminondas himself was killed in the battle and following a damaging struggle amongst his successors and the continued weakness of Athens and Sparta, the short-lived Theban dominance of Greece came to an end, and the Greek cities were now ripe for conquest, a situation Philip II of Macedonia took full advantage of in 338 BCE.