The Battle of Neerwinden saw the major defeat of a French republican army by an allied force of Austrians and Dutch during the War of the First Coalition (1792-97), part of the broader French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). The battle drove the French from Belgium and led French General Charles-François Dumouriez (1739-1823) to defect to the Austrians.

The War Expands

By the end of 1792, the armies of the young French Republic seemed invincible. Revolutionary France's miraculous victory at the Battle of Valmy on 20 September had turned the tide of the war, halting a Prussian invasion in its tracks, saving the French Revolution (1789-99), and emboldening the revolutionaries to abolish their monarchy. In the following weeks, French armies took the offensive; while one army swept into the Rhineland and occupied the cities of Worms, Frankfurt, and Mainz, another pushed into Savoy and Nice, which were conquered without a single shot fired.

Yet the most spectacular of the French successes that year was the Battle of Jemappes on 6 November, when a French army consisting mainly of volunteers invaded Belgium and defeated a professional Austrian force. The first true test of France's revolutionary armies, Jemappes secured the gains made at Valmy, forcing the Austrians from Belgium entirely; by year's end, all of Belgium had fallen under French occupation.

Naturally, France was filled with a sense of triumph. In a scene of patriotic frenzy that had become so familiar during the Revolution, French leaders demanded their armies push ever onward, driving back the enslaved soldiers of despotic Europe. Calls went up for France to expand until its borders reached the Rhine, for nothing less than natural frontiers would ensure the safety of the fatherland. "The frontiers of France have been mapped out by nature," declared Georges Danton, "and we shall reach them at the four corners of the horizon, on the banks of the Rhine, by the side of the ocean and at the Alps. It is there we shall reach the limits of our Republic" (Blanning, 91).

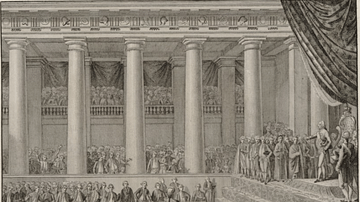

On 19 November, France's National Convention issued the Edict of Fraternity, which promised aid, support, and brotherhood to any peoples engaged in a struggle against tyranny. This was disturbing to most of Europe's regimes, as the edict was essentially an open invitation for extremist groups to rebel against their governments. The edict made no one more nervous than the Dutch Republic and its stadtholder, William V, Prince of Orange; with Belgium overrun, it was only a matter of time before the French Republic decided to complete its conquest of the Low Countries. As the Dutch Republic had seen its own failed revolution in the 1780s, it was feared that the French would claim that Dutch patriots were still being oppressed and would use the Edict of Fraternity as justification for an invasion.

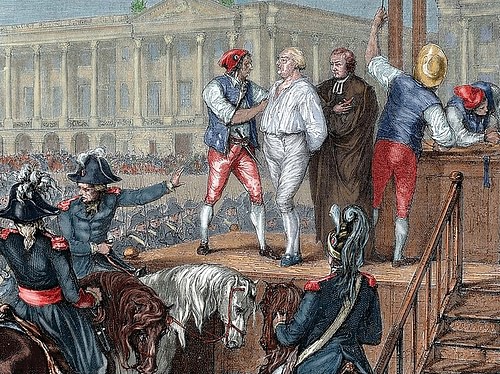

With both Austria and Prussia on the run, the Dutch appealed to Great Britain for protection. The two nations had strong ties with one another, dating back to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 when the Dutch William of Orange ascended the English throne as William III of England (r. 1689-1702). Although the British had affirmed their neutrality as recently as October, their Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806) was beginning to reconsider, especially after the French violated the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia by opening the river Scheldt to navigation. Pitt had no desire for war but could not allow the French to trample across the Low Countries with impunity. On 1 December, he ordered the mobilization of militias. Secret negotiations were opened between the British and French to avoid war, but Pitt put an end to all talks after the trial and execution of Louis XVI of France (r. 1774-1792); Pitt referred to the French king's execution as "the foulest and most atrocious act the world has ever seen" (Schama, 687).

The French, meanwhile, were not put off by the British threat. Overconfident and drunk of victory, the French were certain that in the event of war, Ireland, Scotland, and the remaining British colonies would rise up and join them in the battle against tyranny. The National Convention was so confident that on 1 February 1793 it voted unanimously to go to war against both the British Empire and the Dutch Republic. Britain's entry into the war drew a slew of other European nations into the anti-French coalition, including Spain, Portugal, and Naples. This mattered not to the ecstatic revolutionaries, who believed totally in their cause; "we shall not be calmed," proclaimed revolutionary leader Jacques-Pierre Brissot, "until Europe, all Europe, is in flames!" (Doyle, 201).

Invasion of the Dutch Republic

On the same day that war was declared, General Charles-François Dumouriez, commander of the French forces in Belgium, received orders from the National Convention to invade the Dutch Republic and push into Holland. Despite having led the French to victory at both the Battle of Valmy and Jemappes, Dumouriez had spent the previous month brooding, unsure if he was fighting for a righteous cause. As a monarchist, he had been horrified by the recent execution of Louis XVI of France and was fed up with his Jacobin opponents accusing him of being a new Caesar who aspired to military dictatorship. He bristled under the micromanagement of the National Convention, who sent representatives-on-mission to closely observe him as if he were an untrustworthy deviant rather than a man who had won two major battles.

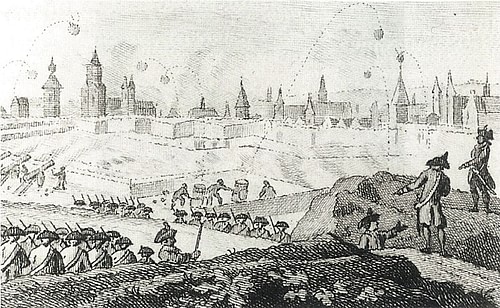

Despite his misgivings, Dumouriez did as ordered and gathered his forces. His army had been depleted in the previous months since many volunteers had gone home after their contracts expired at the end of 1792. Although the Convention had recently issued an order for 300,000 additional soldiers to be raised, by conscription if necessary, Dumouriez did not have the time to wait. On 16 February 1793, he crossed the Dutch frontier with 15,000 infantry and 1,000 horse, marching along the coast toward Breda. Meanwhile, a second French army of 30,000 men under the Venezuelan-born General Francisco de Miranda advanced along the Meuse to the heavily fortified city of Maastricht, on the Belgian-Dutch border, which was besieged on 23 February. The city was held by only 4,500 Dutch defenders, leading Miranda to expect a quick victory.

Meanwhile, Dumouriez captured the key fortresses of Klundert, Breda, and Gertruidenberg with minimal resistance. He next planned to cross the Holland Diep and take Rotterdam, the Hague and finally Amsterdam, anticipating the fall of the Dutch Republic by the end of March. As far as Dumouriez was concerned, victory would be achieved before a coalition army could gather to challenge him, by which point he would be reinforced and resupplied from France. Yet there were two fatal issues with this reasoning: the first being that the National Convention, bitterly divided between the moderate Girondin and extremist Jacobin factions, would have trouble resupplying him, especially as other military fronts began to rapidly appear. The second issue was that a formidable coalition army had already gathered and was now bearing down upon him.

The previous year, the European powers had been unable to give their full attention to the war with France, preoccupied with the question of the second partition of Poland. But by now, that question had been settled, freeing up thousands of troops to turn west. By late February, over 40,000 Austrian soldiers had gathered on the west bank of the Rhine, with the purpose of forcing the French from Holland and reclaiming Belgium for the emperor. This army was under the supreme command of Prince Friedrich Josias of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld, whose lieutenant generals included Karl Mack von Leiberich and the emperor's brother Archduke Charles of Austria, both of whom would one day lead armies against Napoleon.

On the night of 28 February-1 March, Coburg's army crossed the Roer River. Under the cover of darkness, they made their way to Aldenhoven, where a detachment of 9,000 French had been stationed to cover the Siege of Maastricht. Coburg attacked at 5 am, taking the French force completely by surprise. The ensuing battle lasted the entire day, climaxing in a cavalry charge by Archduke Charles that sent the French to rout. The Austrians followed the fleeing French west, seizing the city of Aachen on 2 March. When Miranda heard of the defeat at Aldenhoven, he immediately broke off his siege and withdrew to Louvain.

To the north, Dumouriez was reluctant to give up his invasion of Holland, but when orders from Paris instructed him to personally take command in Belgium, he obeyed. Abandoning his Army of Holland, Dumouriez arrived in Louvain on 13 March where he found a disheartened, demoralized army. Deciding that another retreat would be fatal to the army's morale, Dumouriez marched to face the Coalition forces, who had been reinforced by Dutch troops. He would find them on 18 March on the east side of the Kleine Geete River, on the plains of Neerwinden.

Battle of Neerwinden

The choice of ground was an auspicious one for the French; a full century before, a French army had defeated an Anglo-Dutch force on that very battlefield during the Nine Years' War (1688-97). Despite the desertions that had been plaguing the French armies, the two forces were evenly matched, with Dumouriez commanding roughly 40,000 infantry and 4,500 horse while the Coalition soldiers counted around 30,000 foot and 10,000 horse. Dumouriez's scouts reported that the Austrian position was strongest on their right, where they were protecting their supply lines, so the general decided to direct his first and heaviest blow against their left.

Splitting his army into eight columns, Dumouriez began his attack at 7 in the morning. As the sun rose, the defenders on the Austrian left were greeted by the sight of three French columns swarming across the Kleine Geete. Led by General Jean-Baptiste de Valence, these French soldiers advanced toward the hill of Mittelwinden, hoping to punch through the Austrian lines there. But the Austrian defense was fiercer than anticipated, and Valence did not take the hill until noon, after four hours of savage fighting. The French center, which consisted of two columns led by the young and energetic Louis-Philippe, Duke of Chartres, attacked Neerwinden itself, driving the Austrians from the village. The Austrians recaptured it in a counterattack, only to be driven out once again by Chartres. Throughout the day, the village would keep changing hands, but would ultimately remain under Austrian control by nightfall. To the south, the town of Oberwinden was likewise taken by the French only to be retaken by a spirited Austrian charge.

As battle raged along the French center and right, the final three French columns under General Miranda began their attack at noon, attacking the strong defensive position of Archduke Charles. Again and again, Miranda's men hurled themselves against the Austrian positions, only to be repelled every time. Some of the bloodiest fighting of the day happened here, where the French lost 2,000 men, 30 officers, and one general. Once the French had worn themselves out, the Archduke ordered a devastating cavalry charge, which succeeded in driving Miranda back across the river and to the town of Tirlemont. This was the deciding moment which ensured victory for the allies.

As night fell, the two armies were in much the same position they had been in that morning, with the exception of the French left flank, which had been totally routed. On the morning of the 19th, rather than renewing an attack with his flank exposed, Dumouriez ordered a retreat to Louvain. Overall, the French had suffered 4,000 killed and wounded, with an additional 1,000 taken captive. Austrian losses were also substantial, suffering 2,700 killed and wounded, including 97 officers.

Dumouriez's Betrayal

Coburg followed the retreating French, determined to capitalize on his victory. He met the French again in a minor engagement at Louvain on 22 March, forcing Dumouriez to retreat even further, to Brussels. By now, Dumouriez's forces had dwindled to only 20,000, as volunteers were deserting in droves. Realizing he could not withstand another battle, Dumouriez asked to negotiate a retreat.

Initially, Dumouriez had only intended to request to be able to retreat unmolested in return for evacuating Belgium. But upon meeting with Coburg's second-in-command, General Mack, to discuss the terms for retreat, he offered up an entirely different plan. If the Austrians would agree to a general suspension of hostilities, Dumouriez promised to not only leave Belgium but to also turn his army around and march on Paris itself. Once he was in the capital, he intended to arrest the Jacobins, dissolve the National Convention, restore the monarchy, and proclaim the late Louis XVI's eight-year-old son as King Louis XVII of France. Mack, aware that the Austrian army had been badly bloodied, thought that it could not hurt to let Dumouriez attempt his proposed coup. After consulting with Coburg, he agreed to let Dumouriez leave Belgium unmolested in return for the French general's march on Paris.

Dumouriez's treason may seem surprising; after all, this was the man who had saved the Revolution from destruction at Valmy and had conquered Belgium for the Republic at Jemappes. Yet, Dumouriez was greatly disturbed by Louis XVI's execution and did not approve of the direction the Republic was heading. Moreover, even at this early stage in the war, paranoid revolutionary leaders had begun to accuse defeated generals of treason, leading Dumouriez to favor a preemptive strike over allowing himself to be led to the guillotine. Of course, there would also be the personal satisfaction of seeing the destruction of the Jacobins, who had been personally attacking him for so long.

Just as General Lafayette had attempted to do less than a year earlier, Dumouriez now faced the daunting task of convincing his army to march on Paris. Yet while it is true that a large portion of his soldiers hated the new National Convention, most of them still believed in the Republic and were not willing to commit treason. Dumouriez spent the last days of March sitting on the Belgian frontier as he tried to garner support for his coup. But with every day he delayed, he appeared more suspicious. Eventually, General Miranda slipped out of his camp and went to Paris where he began spreading rumors that Dumouriez was planning something. In April, the French minister of war, Pierre de Beurnonville, was sent to investigate Dumouriez's conduct. When he arrived at Dumouriez's camp, Beurnonville, who had served under Dumouriez at Jemappes, was arrested, along with five commissioners from Paris, and was delivered to the Austrians in shackles.

With Beurnonville's arrest, Dumouriez had crossed the point of no return. Time was against him, but he was no closer to convincing his army to join him in treason. His men became so hostile toward him that he was forced to walk around with an escort of Austrian soldiers, which only increased his unpopularity. The tipping point came on 5 April, when a battalion of French volunteers under Louis-Nicolas Davout attempted to arrest Dumouriez, even firing at him. Realizing his cause was hopeless, Dumouriez and a handful of supporters fled to the Austrian camp that very day. With him went the Duke of Chartres, who had fought so valiantly for the Republic at Valmy, Jemappes, and Neerwinden. Although Chartres would not set foot in France until after Napoleon's final defeat, he would one day reign as its last king, Louis-Philippe I (r. 1830-1848).

Aftermath

Following Dumouriez's defection, Coburg pressed on with an invasion of France, seeing as there was no longer a reason for him to honor the suspension of hostilities. General Picot de Dampierre was given command of Dumouriez's forces and continued to defy the Coalition attack until he was killed at Raismes about a month later. Just as France's victory at Jemappes had seen it take the offensive, its defeat at Neerwinden had the opposite effect. As Coburg restored Belgium to Austrian rule, another French army was pushed out of the Rhineland, and 20,000 French soldiers were besieged in Mainz.

With the execution of the king, the political climate in Paris was already tense; Dumouriez's betrayal made it even more so. News of his defection worsened the conflict between the Girondins and Jacobins, helping to lead to the arrest of many leading Girondins on 2 June, and their subsequent executions. The betrayals of both Lafayette and Dumouriez less than a year apart also led the Convention to tighten its grip on the armies, as representatives-on-mission were given ultimate authority over the generals.

As for Dumouriez, he spent the months after Neerwinden in Brussels before moving to Cologne, where he unsuccessfully sought a position in the court of the elector. Learning he had become reviled as a traitor by his countrymen and viewed with suspicion by the rest of Europe, he wrote his memoirs in 1794 to defend his actions, publishing them in Hamburg. In 1804, he settled in London, where he was granted a pension by the British government, who he advised in their efforts to defeat Napoleon. He remained in London after the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) until his death on 14 March 1823.