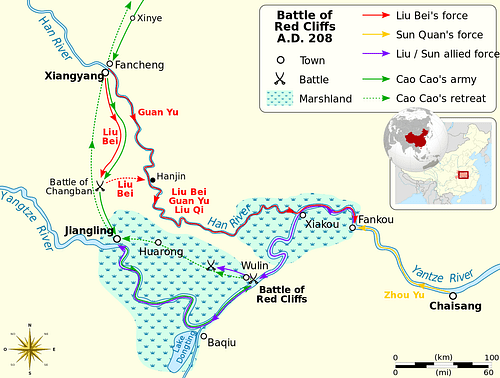

The Battle of Red Cliffs (also known as the Battle of Chibi, 208 CE) was the pivotal engagement between the forces of Northern China led by the warlord Cao Cao (l. 155-220 CE) and the allied defenders of the south under the command of Liu Bei (d. 223 CE) and Sun Quan (d. 252 CE). The battle is considered the turning point in the conflict between various warlords who assumed control of their regions and then extended their reach in the waning days of the Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE). Cao Cao was defeated by the southern coalition and driven back north, ending his dream of unifying China under his rule.

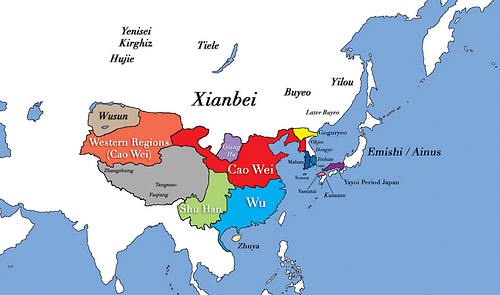

The engagement leveled the playing field of the central antagonists as, previously, Cao Cao had been the most powerful and commanded the largest army. Afterwards, with Cao Cao beaten and forced to retreat with heavy losses, Liu Bei and Sun Quan stabilized their regions and this eventually led to the Three Kingdoms Period (220-280 CE) following the end of the Han Dynasty with Cao Cao ruling the kingdom of Cao Wei, Liu Bei reigning over Shu Han, and Sun Quan as king of Eastern Wu. The Three Kingdoms remained in often uneasy truce with each other until they were united in 280 CE under the Jin Dynasty.

Han Dynasty Decline & the Yellow Turban Rebellion

The Han Dynasty, which had liberated China after the repressive rule of the Qin (221-206 BCE), had become increasingly corrupt by c. 130 CE. The central reason given by later Chinese historians was the evolution of the role of palace eunuchs in the Chinese government. The eunuchs were originally no more than harem guards, chosen to ensure the safety and sexual purity of the Chinese emperor's many concubines, but their proximity to the emperor and ready access to court intrigues made them valuable assets to the nobility. Eunuchs could, and did, play important roles in elevating some members of the nobility and disposing of others. Further, they provided the emperor with a buffer between himself and the various parties seeking his favors.

By c. 130 CE, the eunuchs were the actual power behind the throne, manipulating the government and pushing through their various agendas. Government positions could now be bought from the eunuchs and were filled by various undeserving relatives of the upper class who could afford the price. The once-efficient bureaucracy of the Han declined as more and more of the upper class, who had no training in government administration, filled the posts, collected their pay, and neglected their duties.

In 142 CE, a peasant movement known as the Five Pecks of Rice Rebellion was launched by a Taoist visionary named Zhang Daoling who essentially gave notice that he and his sect were seceding from Imperial China to form their own state where they could better take care of themselves. The Han, who favored Taoist thought, seem to have given Zhang and his followers little thought and less notice as nothing was done about them until 215 CE and, even then, it was not the Han who brought the region back in line, but Cao Cao who was pursuing his own agenda in doing so.

Perhaps encouraged by the relative success of the Five Pecks movement, a Taoist healer named Zhang Jue initiated his own revolt in 184 CE, the Yellow Turban Rebellion, which quickly caught the people's imagination and spread across the country rapidly. Zhang condemned the Han as selfish and self-seeking aristocrats who had lost the Mandate of Heaven by which they had the right to rule. The Mandate of Heaven, dating back to the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE), was a spiritual contract between the ruling house and the gods legitimizing a dynasty and evident in the ruling house's care for the people. The people, Zhang pointed out, were suffering while the nobility did nothing to help them.

Zhang focused his movement on the principle of jiazhi (“worth”), the fundamental, intrinsic value of an individual and, by extension, the actions of that individual. Each person had a divine value, no matter their social class or contribution to society, and this was being ignored by the government officials who squandered resources, wasted time and energy, and pursued their own petty interests all at the expense of the people they were supposed to be serving.

The Yellow Turban Rebellion (so-called because of the yellow headgear rebels wore, symbolizing the earth) soon had active enclaves all over China and Zhang worked to arm the peasants for the conflict he knew would come when the Han chose to act. He did not have to wait long because the Han were not about to let this kind of agitation go as it had the Five Pecks Rebellion.

Rise of the Warlords

The emperor Lingdi (r. 168 -189 CE) had continued the policies of his predecessors in elevating regional governors to military positions to guard the borders against invasions by the nomadic Xianbei and Xiongnu and many of his best generals were therefore far from the capital. Lingdi sent his generals Huangfu Song (d. 195 CE), Lu Zhi (d. 192 CE), and Zhu Jun (d. 194 CE) against the rebels but as soon as one enclave was crushed, another appeared elsewhere.

A court official (who was also a regional governor) named Liu Yan (d. 194 CE), suggested that the emperor empower his provincial and regional officials by releasing them from imperial dictates and allowing them to handle the rebellion in their own territories as they best saw fit. In doing so, Lingdi would be encouraging the formation of a number of autonomous states within his realm but, at a loss for a better plan, he agreed to it. One of these regional officials was Cao Cao who seized on the new freedom and crushed the rebellion within a year. Zhang Jue was either killed in battle or executed and the revolt was crushed by the end of 184 CE.

Other regional governors had likewise flexed their new muscles, now becoming warlords and, after the rebellion was put down, set about administering their provinces as they chose and claiming lands without reference to the emperor or court policy. Lingdi died in 189 CE, leaving the throne to his son Liu Bian, at that time around the age of 12, who became Emperor Shao of Han. He was too young to rule, however, and so a regent – his uncle He Jin – was placed over him. The eunuchs wanted control of the new emperor, however, and plotted to assassinate He Jin at the same time that He Jin sent word to outlying warlords Dong Zhuo (d. 192 CE) and Yuan Shao (d. 202 CE) to come to Luoyang and help him dispose of the eunuchs.

The eunuchs discovered He's plan and assassinated him, but this did them little good since Yuan Shao then slaughtered them all when he arrived at the city and found He Jin dead. While the eunuchs and their supporters were being massacred, the young emperor, his brother Liu Xie, and their family escaped the city and were on their way to Chang'an when they were intercepted by Dong Zhuo, marching toward Luoyang. Dong took the emperor and his entourage and, now holding the imperial seal, declared himself the supreme power.

The Alliance & Conflict

The other warlords, including Cao Cao, objected to this and formed an alliance to overthrow Dong known as the Guandong Coalition (c. 190-192 CE). The 26 warlords surrounded Luoyang with their armies but Dong escaped, setting the city on fire and herding the populace, including the emperor, toward Chang'an which he fortified. The warlords claimed they were fighting for the restoration of the Han Dynasty and to rescue the emperor while Dong claimed the emperor was his guest and in no danger. Dong actually favored the emperor's younger brother, Liu Xie, for rule and, in 190 CE, had Emperor Shao executed and Liu Xie became Emperor Xian.

The warlords again tried to topple Dong but he was too well protected. He was finally killed by his confidante and bodyguard Lu Bu and, after his death, the coalition broke apart and turned on each other. Emperor Xian was now held at Chang'an, under the influence of whichever warlord was strongest at a given time, until he escaped in 195 CE and fled north, eventually finding refuge with Cao Cao.

Cao Cao now held the key to legitimate rule with the emperor and Imperial Seal within his borders. If the alliance had ever actually cared about restoring the Han to power, this was the moment when they could have made that clear and either rescued the emperor or restored him to power. Instead, Cao Cao and the others continued the power struggle, killing each other off and absorbing lands, while the emperor remained under the 'protection' of Cao Cao and could do nothing.

Cao Cao defeated every opponent, steadily enlarging his territory until he held the entirety of the North China Plain. He defeated Yuan Shao, one of his oldest friends and comrades-in-arms, at the Battle of Guandu in 200 CE, solidifying his hold on more territories and expanding his armies. Between 200-207 CE, Cao Cao continued his campaigns, building a tremendous army, until all he needed to do was march south and join those territories to his own in order to unify China under his rule.

Red Cliffs

Cao Cao set off in the late summer of 208 CE with an army (according to his own estimation) of almost 800,000 warriors. Modern-day scholars and even Cao Cao's contemporaries claim this is a wild exaggeration and he probably had closer to 250,000 men, but even so, this was an incredibly large army, especially when one considers that his opponents could field only between 10,000-50,000 troops.

The first objective was to capture the port city of Jiangling on the Yangtze River which would enable Cao Cao to control trade as well as supply troops quickly throughout the south. He met no resistance on his march toward Jiangling, but he knew the other warlords would be waiting for him once he reached the city.

While Cao Cao was on the march, a new coalition had formed against him headed by Liu Bei of Han and Sun Quan of Wu but including a number of notable generals such as the great Guan Yu (d. 220 CE), so famous for his martial skills and personal honor that he was later deified as Guan Gong (also known as Guandi), god of war and protection, and the brilliant strategist Zhou Yu (d. 210 CE). Guan Yu was in charge of troops' river passage while Liu Bei, whom he served, marched by land.

The first skirmish came when Cao Cao attacked Liu Bei's columns, scattering them, and Guan Yu rescued the troops and brought them downriver. Cao Cao would probably have won at this point, but his men were tired from the long march and, unused to the southern climate and terrain, they were disoriented, many of them ill. Guan Yu was able to easily rescue Liu Bei's troops whereas, in the past, Cao Cao had proven himself a thorough strategist who planned for every contingency and would never have let that happen.

Among the many problems the southern campaign presented to him was transporting land troops by water. Cao Cao had gained a significant number of ships through his earlier victories and planned on using them to subdue the south along the Yangtze River. His men, used to land battles, became seasick and, probably in response to this, Cao Cao had the boats lashed together to prevent rocking so the fleet was one entire block of ships rather than separate boats able to maneuver.

Once Cao Cao had positioned his army on the southern bank of the Yangtze, he docked his floating fortress nearby, which inspired one of the coalition generals, Huang Gai (d. 210 CE), with a plan for Cao Cao's defeat. Huang Gai, a division commander with a number of ships at his disposal, contacted Cao Cao claiming he wanted to defect and bring his fleet with him. Cao Cao happily accepted his offer and awaited his arrival. Huang Gai then filled the boats with flammable materials and oil and had a skeleton crew sail them out onto the river. When they were halfway across, with the winds now moving them steadily forward, the sailors fired the ships and then slipped off onto smaller boats. The ships were coming too fast and were too close for Cao Cao to do anything to stop them and they slammed into his fleet, setting it on fire.

As the ships burst into flames, Zhou Yu burst onto Cao Cao's encampment with a land contingent, killing and scattering Cao's men. Cao Cao recognized the day was lost completely and sounded a general retreat back north with Zhou Yu, Liu Bei, and Sun Quan's forces pursuing them. The path the retreating army needed to take, the Huarong Road, was a muddy track which made for slow going and many of the men were sick, all of them most likely demoralized, and more died on the retreat north than at the brief Battle of Red Cliffs.

Conclusion

Once Cao Cao was back in Wei, he resigned himself to his defeat, proclaimed himself king of his territories, and established the Kingdom of Cao Wei. Liu Bei followed suit in the south, founding the Kingdom of Shu Han and Sun Quan did the same with his Kingdom of Eastern Wu. China was now divided in three – the era known as the Three Kingdoms Period – with each monarch claiming the Mandate of Heaven to rule all of China but each lacking the strength to subdue the other two.

The Han Dynasty still technically ruled China because Emperor Xian still lived at Cao Cao's court. When Cao Cao died in 220 CE, his son Cao Pi forced the emperor to abdicate and founded the Wei Dynasty (221-265 CE) which was mirrored by the other states of Shu Han and Eastern Wu which each saw themselves as the legitimate heirs to the Han and Liu Bei and Sun Quan both proclaiming themselves emperors. China would remain divided along these lines until it was unified by the Jin Dynasty in 280 CE.

The Battle of Red Cliffs and the Period of the Three Kingdoms is one of the best-known and most highly romanticized engagements and eras in Chinese history thanks to the 14th-century CE bestselling novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong. The novel, a work of historical fiction, is responsible for the sinister reputation of Cao Cao as a ruthless villain, characters such as Liu Bei and Sun Quan as heroes, and magical events – such as summoning of the winds to blow the fire-ships toward Cao Cao's fleet – as part of the plot development. The novel was incredibly popular and is still read in the present day. In 2008 CE, director John Woo released the film Red Cliff to popular and critical acclaim and the battle is the subject of video games and other works.

Based on this media – as well as operatic performances and artwork – Cao Cao is routinely depicted as the ultimate villain, intent on conquering China at any cost, while Liu Bei and Sun Quan are seen as the patriotic heroes defending the freedom of their homeland against a ruthless tyrant. In reality, none of the parties who met at the Battle of Red Cliffs had the people of China's interest at heart and none of them had a legitimate claim to the Mandate of Heaven. Each vied with the other purely out of their own self-interest, and the people they were supposed to be fighting for paid the price for their ambition.