The Battle of the Little Bighorn (25-26 June 1876) is the most famous engagement of the Great Sioux War (1876-1877). Five companies of the 7th Cavalry under Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876) were wiped out in one day by the combined forces of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors under the Sioux chief Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890).

Custer located Sitting Bull's camp by the banks of the Little Bighorn River (known to the local Native Americans as the Greasy Grass) in modern-day Montana but had no idea how large it was or how many warriors were present. Having been given a free hand to wage total war against the Plains Indians, Custer divided his command as he had in 1868 at the Washita Massacre. His plan was to attack the camp from opposite sides and close on it in a pincer movement, capturing the women and children as hostages, and forcing whatever warriors had not been killed to surrender. He sent Captain Frederick Benteen (l. 1834-1898) to scout, and Major Marcus Reno (l. 1834-1889) to position himself to strike at the far side.

When Reno launched his attack, however, he was met by a large force of warriors under Sioux war chief Gall (l. c. 1840-1894). Benteen, who had been ordered to bring ammunition to Custer's position, instead tried to support Reno but wound up joining him in retreat. While Gall was driving back Reno and Benteen, Sioux war chief Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877) led a charge against Custer's position.

Custer and all five companies with him were killed in what has come to be known as "Custer's Last Stand." The battle was a decisive Native American victory but could not be capitalized upon because of the public outcry for revenge for the death of Custer, a popular hero of the American Civil War who had also made a name for himself as an Indian Fighter.

After the Battle of the Little Bighorn (also known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass), the Native American leaders went their separate ways to avoid capture and execution. The last major engagements of the Great Sioux War were US victories (or a draw, in the case of the Battle of Wolf Mountain), and, with the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and others pushed onto reservations, the Great Plains were open for colonization.

Background

According to the Yanktonai Sioux Chief Lone Dog's Winter Count (a yearly account of events from 1800-1870), "White soldiers made their first appearance in the region" in 1823-1824 (Townsend, 128). The Sioux had little to do with them until 1854 when 2nd Lieutenant John L. Grattan arrived at the camp of Sioux Chief Conquering Bear (l. c. 1800-1854) and demanded the surrender of a man he claimed had stolen a cow from a passing wagon train of Mormons. Conquering Bear refused the demand, Grattan's men opened fire (mortally wounding Conquering Bear), and the Sioux then slaughtered Grattan and the 30 troops under his command in what came to be known as the Grattan Fight or the Grattan Massacre, leading to the First Sioux War of 1854-1856.

Prior to the Grattan Fight, the US government had negotiated land rights and territories with several nations of Plains Indians, including the Sioux and the Cheyenne, through the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, which stipulated, among other terms, that the United States had no claim on the lands occupied by those nations. Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle (l. c. 1803-1868) was among those who signed the treaty, which was never honored by the United States and was broken in 1858 when gold was discovered in the region, prompting Pike's Peak Gold Rush and an influx of settlers. Further encroachments led to the Colorado War (1864-1865), during which Black Kettle's peaceful village, flying the American flag and the white flag of truce, was attacked in the Sand Creek Massacre of 29 November 1864.

As more settlers claimed Native American lands as their own, Oglala Sioux Chief Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909) launched Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) in defense of his people's land and to force the United States to honor its treaty. The war concluded with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 but, that same year, Black Kettle, his wife, and between 60-150 Cheyenne and Arapaho were slaughtered by troops under Custer's command at the Washita Massacre on 27 November. The treaty of 1868 established the Great Sioux Reservation, but this was broken when, in 1874, Custer discovered gold in the Black Hills, sacred to the Sioux (and other nations) and part of the lands promised them. The Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876 that resulted from Custer's find ignited the Great Sioux War when the US government demanded the Sioux sell the Black Hills and the Sioux refused.

Custer, Grant & Command

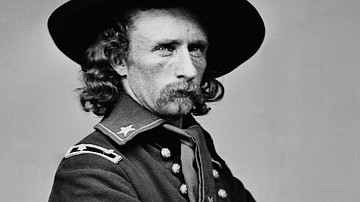

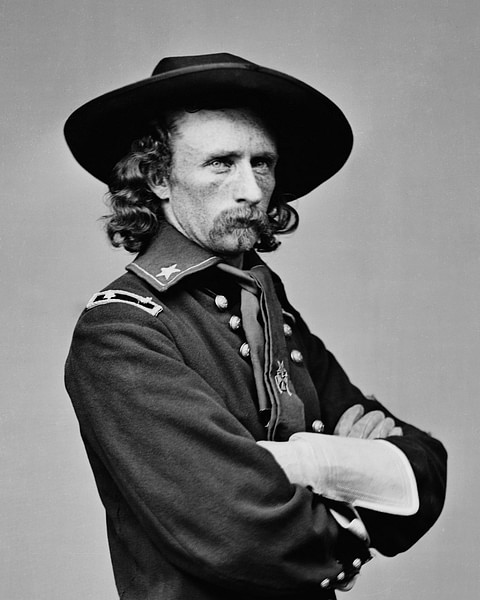

George Armstrong Custer was a general in the Union army during the American Civil War (1861-1865) who became a war hero after the Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863 and accepted the rank of Lt. Colonel in the peacetime army after mustering out in 1866. By 1867, he was serving under Major General Winfield Scott Hancock (l. 1824-1886) in campaigns against the Cheyenne. On 19 April 1867, Hancock surrounded the Cheyenne village at Pawnee Fork but when he ordered the attack, he found no one there; all the people had slipped away. Custer would remember this lesson later when he surrounded the camp of Chief Black Kettle on 27 November 1868 in the engagement known as the Washita Massacre (or Battle of the Washita River) and again in 1876 at the Little Bighorn.

President Ulysses S. Grant (served 1869-1877), after the Sioux had rejected his bid to buy the Black Hills, sent the ultimatum that the Sioux could either move onto reservations designated by the US government by 31 January 1876 or be designated 'hostiles'. Colonel Joseph J. Reynolds (l. 1822-1899) campaigned against the Northern Cheyenne and Oglala Lakota Sioux in 1875 and, when the Sioux still ignored Grant's demands, General George R. Crook (l. 1828-1890) and General Alfred H. Terry (l. 1827-1890) were sent against them in February 1876.

Custer was to lead his command in support of Crook and Terry when, in March 1876, he was called to Washington, D.C. to testify before Congress on allegations that Secretary of War William W. Belknap and Grant's brother Orville had been forming monopolies of trading posts out west, forcing settlers, miners, and soldiers to pay high prices for basic necessities.

Custer's testimony led to Belknap's impeachment, Orville's public humiliation, and outcry over corruption in Grant's administration. Custer, feeling he had done as asked, prepared to return to his troops, but Grant removed him from command and ordered him to remain in Washington, D.C. When Custer ignored the order and left the city, Grant had him arrested when he stepped off the train in Chicago. The press covered the arrest, resulting in public outrage over Grant's poor treatment of a war hero, and General Philip Sheridan (l. 1831-1888), among others, pressed the president for Custer's release. Grant relented but refused to allow Custer full command, instead placing him under General Terry.

Sitting Bull's Camp & Battle of the Rosebud

Once he was back out west with his troops, Custer was ordered by Terry to seek out and attack the camp of Sitting Bull, which was thought to be somewhere along the Rosebud or Little Bighorn rivers. As far as Terry was concerned, unofficially anyway, Custer had full command of the 7th Cavalry and could act as he saw fit once the camp was located: killing the warriors, kidnapping women and children, and destroying horses and food supplies. This was in keeping with Sheridan's policy of 'total war', which Custer had followed earlier at the Washita Massacre.

While Custer scouted for what he thought was a single chief's village, Sitting Bull had assembled a huge host of Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, all gathered to form a united front against the invasion of their lands and the broken treaties. Scholar Joseph M. Marshall III writes:

Sitting Bull, like many of his generation, watched the influx of whites into Lakota territory turn into encroachment on everyday life. It soon became an outright invasion that had killed off most of the Buffalo herds on the northern plains by 1875, and more and more white miners infested the Black Hills because of the discovery of gold there. These were only some of the alarming realities that Sitting bull wanted to change before it was too late. To do so, he had to work with the leadership hierarchy that existed among the Lakota. He had to talk to the older men who were the heads of families and villages, and to his contemporaries. That was the primary reason he issued the call for the people to gather in the spring of 1876.

(68)

In early June, at the Sun Dance, Sitting Bull had a vision of soldiers falling and falling and falling all around him, which he interpreted as a promise from the spirit world of a great victory.

While Sitting Bull convened meetings, Crazy Horse sent scouts out to watch for the approach of US soldiers. He was alerted to the presence of General Crook in the area of the Rosebud and launched an attack on 17 June (the Battle of the Rosebud, known by the Cheyenne as the Battle Where the Girl Saved her Brother). Crook would have been taken completely by surprise, but his Crow and Shoshone scouts warned him of Crazy Horse's approach, and he was able to raise defenses. Still, he was driven from the field, and although he claimed he had won, it was actually a victory for Crazy Horse. The Cheyenne name for the engagement comes from the moment when Buffalo Calf Road Woman saved her brother, Comes-in-Sight, when his horse was shot out from under him. Sitting Bull's camp was still elated from this victory as Custer approached.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

General Terry and Colonel John Gibbon (l. 1827-1896) were marching their commands toward the Little Bighorn when, before dawn on 25 June, Custer found Sitting Bull's camp. Among his scouts were several Crow and Arikara, including the Sioux-Arikara Bloody Knife (l. c. 1840-1876), Custer's friend and confidante. Bloody Knife, as well as some of the other Native American scouts, warned Custer that the village was larger than he thought and so could field a greater number of warriors, but they were ignored.

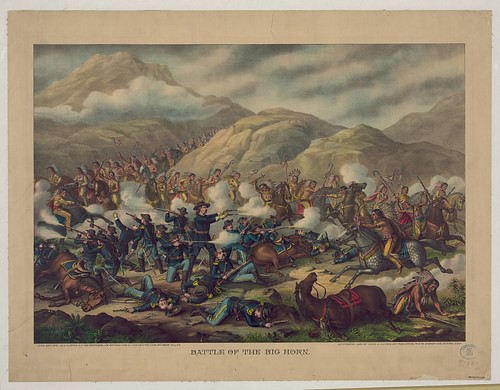

Custer decided on the same tactic he had used at Washita and divided his twelve companies into three battalions. He would command five, Reno three, Benteen three, and the 12th would guard the pack train. At Washita, Custer had sent out his officers to surround the village and converge on his command, and his plan had worked perfectly, so there was no need to worry about it failing now. Benteen was sent to scout, Reno to attack the village from the far side, and Custer would close from his side. Reno expected to surprise the camp and scatter any warriors but had no idea how many warriors were in the camp or their resolve, so, when he struck, he was met by stiff resistance, and his charge failed and then turned into a rout as Chief Gall lead a counter charge into them. Bloody Knife, who had been assigned to Reno was killed by a shot to the head.

Reno fled back across the river where he met Benteen's company. Benteen received a note delivered to him by the bugler John Martin from Custer telling him to come quickly and "bring packs" – referring to the pack animals that carried ammunition. Benteen, who had hated Custer since Washita, ignored the order and chose to stay and support Reno. Benteen, Reno, and others could hear the sounds of gunfire and assumed Custer had engaged the enemy but did not think they needed to do anything about that and, besides, had their own situation to deal with. Captain Thomas Weir (l. 1838-1876) ignored Reno's order to remain at his post and rode out to assist Custer, but, upon reaching the crest of a hill, saw so many Native American warriors below, he understood this would be impossible and returned to his position.

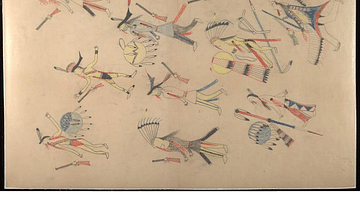

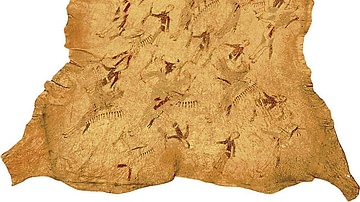

After Gall had stopped Reno, Crazy Horse had charged Custer's position. The battalion under Captain Myles Keogh (l. 1840-1876) was wiped out by a joint attack by Crazy Horse and Gall, but who precisely reached Custer's position first and what happened during "Custer's Last Stand" is unknown. According to Cheyenne history, Custer was knocked from his horse by Buffalo Calf Road Woman and then killed. Who killed him is unknown, though there were claims it was the Sioux warrior Rain-in-the-Face (l. c. 1835-1905). Rain-in-the-Face denied this, however, and was also among the many who described the battle as chaotic and, with all the dust raised, how it was impossible to see clearly. The chaos of the conflict is described by the Oglala Lakota Sioux visionary and medicine man Black Elk (l. 1863-1950), who was twelve years old at the time, in the account known as Black Elk on the Battle of the Little Bighorn from Black Elk Speaks:

It was all dust and cries and thunder…Off toward the west and north they were yelling, "Hoka Hey!" like a big wind roaring, and making the tremolo and you could hear eagle bone whistles screaming. The valley went darker with dust and smoke and there were only shadows and a big noise of many cries and hoofs and guns.

(68)

Besides the dust and confusion, Native American veterans interviewed later said they had no idea Custer – who they called "Son of the Morning Star" for his tactic of attacking at dawn – was even present until long after the event so, most likely, even the person who killed Custer would not have known who he was.

As no one from Custer's command survived, there is no record of his "last stand" and the famous image of him with long, blonde hair and a broad-brimmed hat, wearing his buckskin jacket, guns blazing, is a later fabrication encouraged by his wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer (l. 1842-1933), who established his legacy as a great American hero through her books and speaking tours. Custer had shaved his head before the battle, the buckskin was too warm to wear in Montana territory in June, and no one knows what weapons he had in hand when killed. His body was found on 27 June when Terry and Gibbon arrived. He had been stripped naked and had a gunshot wound to his left chest and another to his left temple.

It is thought the shot to his chest killed him and the one to his head came later when the warriors, as they reported, fired at the bodies to make sure they were dead. Unlike the rest of Custer's command, his body was not ritually mutilated nor was he scalped. According to the Cheyenne, this was because he had taken Monahsetah (l. c. 1850-1922), daughter of Cheyenne chief Little Rock, who was killed at the Washita Massacre, as a mistress, making him 'family'. These same reports also claim that Cheyenne women jammed their sewing awls into Custer's ears so he would "hear better in the afterlife" and not attack innocent women and children. These accounts, however, contradict the others claiming no one knew Custer was on the field that day.

Conclusion

The Arapaho-Cheyenne-Sioux coalition had so far won every battle of the Great Sioux War, but that changed dramatically after the Battle of the Little Bighorn. News of Custer's death and the massacre of his command spread quickly, and the Euro-American public was outraged and wanted these deaths avenged. The problem was the military could not locate Sitting Bull or any of the others. After the battle, the Native American leaders pursued their own paths: Gall and Sitting Bull fled to Canada, and Crazy Horse simply eluded the cavalry by constantly moving around the Great Plains.

There were skirmishes, like the Battle of Warbonnet Creek in July, but no full engagements. The US government issued the Indian Appropriations Act on 15 August 1876, demanding the Sioux sell the Black Hills for a price the government set, or else provisions and clothing would be withheld from those on reservations. Still, Crazy Horse, and others, refused to surrender the land and continued the fight.

The Battle of Slim Buttes (9-10 September 1876) was the first full engagement after Little Bighorn and a victory for General Crook who destroyed the village of American Horse the Elder (l. c. 1830-1876). Colonel Nelson Miles (l. 1839-1925) fought Crazy Horse to a draw at the Battle of Wolf Mountain (8 January 1877) but claimed it as a victory. The Battle of Muddy Creek (7 May 1877) was more of a massacre of the village of Lakota chief Lame Deer (l. c. 1821-1877), but certainly a victory for the US military, and it concluded the Great Sioux War. Crazy Horse surrendered on 5 May, and the others would do the same in the coming years. The Battle of the Little Bighorn was the last great victory of the Plains Indians in defense of their lands, which were then claimed by the US government and settled by its citizens.