The Bismarck was a German battleship, the largest and most powerful capital ship in the Kriegsmarine. For all its weaponry and armour, the ship was involved in only one major operation which, after the sinking of the British battlecruiser Hood, ended in the Bismarck's destruction in the North Atlantic by a large British force on 27 May 1941.

A New German Navy

The Kriegsmarine, created in May 1935, was a new navy that finally broke out from the restrictions that had been imposed on German naval forces since their defeat in the First World War (1914-1918). The Treaty of Versailles limited the number and size of ships in Germany's navy. The purpose of the navy, the victorious allies stipulated, was merely the defence of the German coast. From 1933, though, the new chancellor Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) was determined to build a far more powerful navy, in particular, one with ships that could match the Royal Navy's battleships with their huge 15-inch guns. In June 1935, the Anglo-German Naval Agreement was signed, which capped the Kriegsmarine's total strength to 35% of the Royal Navy but did allow Hitler to realise his ambition of building giant battleships. The new battleships were designed to protect battle groups whose mission was to sink enemy merchant vessels in wartime. As it turned out, when the Second World War started in 1939, battleships were primarily used to occupy enemy vessels as a game of cat-and-mouse was played out to ensure Germany's great battleships did not roam the high seas.

The Bismarck Class

Germany set about building two great battleships, sister ships of an entirely new class, the Bismarck class. These ships would match anything in service in the Royal Navy. The two ships were the Bismarck, named after the former German chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1819-1898), and the Tirpitz, named after Großadmiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930). The two ships were such a giant undertaking they became important prestige projects for Nazi Germany. Each was longer, wider, and heavier than anything ever incorporated into Germany's navy.

Bismarck was built in Hamburg at the Blohm and Voss shipyard. Work had begun on 1 July 1936. The Bismarck's hull was protected by armour 12 inches (32 cm) thick, a 2-inch (5 cm) armoured deck, a 3 to 4-inch (8 to 11 cm) thick interior sloping armoured deck, 12-inch thick armour around the engines, boilers, and magazines, and 22 watertight compartments. The hull was officially launched on 14 February 1939. Hitler gave a 15-minute speech and watched Otto von Bismarck's granddaughter, Dorothea von Loewenfeld, do the christening honours as the hull slipped into the water. Fitting out took over a year and involved a change to a modern raked or 'Atlantic' bow. Bismarck entered service on 24 August 1940. Her first and only captain was Ernst Lindemann (1894-1941). The ship fired its guns against enemy aircraft bombing Hamburg just before sea trials were conducted in September, the ship sailing to Gotenhafen (today's Gdynia, Poland) in the Baltic. More sea trials came in March 1941, and with Bismarck looking good, the ship was declared combat-ready in May. The importance of the battleship to Germany's war effort is indicated by a personal inspection by Hitler on 5 May.

The Allies were well aware of Bismarck's progress. Prime Minister Winston Churchill (1874-1965) described the ship as "the most powerful, as she is the newest, battleship in the world" (Boatner III, 328). Widely considered unsinkable, for many of the crew, the heavily-armoured Bismarck seemed about the safest place to spend the war. However, like that other famous unsinkable ship RMS Titanic, Bismarck would not survive its first voyage.

Specifications & Armaments

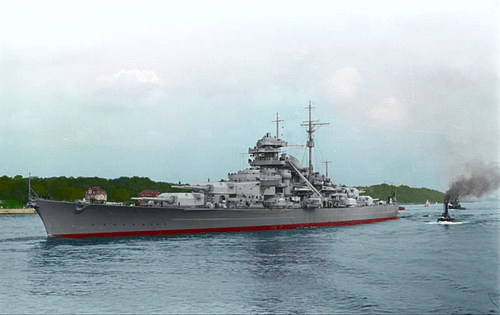

Bismarck measured 821 feet (250.5 m) in length with a berth of 118 feet (36 m). The width was unusual but allowed for a shallower draught, and it made the ship more stable when firing the massive guns. When loaded, Bismarck displaced 50,900 tons (much more than the 35,000 tons permitted by the Anglo-German Naval Agreement). Around 44% of the ship's weight was armour plating. The three steam-turbine engines were fed by 12 boilers and powered three propellor shafts. The top speed was 30.8 knots. The ship had a catapult to launch its complement of four aircraft, Arado 196 floatplanes, which were used for reconnaissance sorties. A crane picked up the planes from the sea. The crew of the Bismarck numbered 2,092.

The ship was positively bristling with 62 guns in all; the largest were eight 15-inch (38 cm) guns split into pairs in four separate turrets called (aft to forward) Dora, Caesar, Bruno, and Anton. Each barrel of these giant guns weighed over 1,000 tons. There were 12 6-inch (15 cm) guns in six turrets, 14 4-inch (10.5 cm) flak guns in seven turrets, 16 1.5-inch (3.7 cm) flack guns in eight turrets, and 12 0.8-inch (2 cm) flak guns in either single or quadruple turrets. The biggest guns could only fire two shells a minute, but the 1,760-lb (800 kg) shells could be propelled a distance of 22.7 miles (36.5 km).

The ship was given a black and white 'Baltic' camouflage on its hull and superstructure using peculiar angled stripes that disguised its form when seen from an enemy vessel. The ship was made to look shorter by false waves at the bow and stern.

Active Service

The Bismarck was to form a battle group with two other ships, the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen and the battlecruiser Gneisenau. In a three-month mission known as Operation Rheinübung, the group was tasked with attacking enemy convoys, Bismarck drawing off their escorts and so leaving the merchant ships easy targets for Prinz Eugen and Gneisenau. This would be an entirely new threat to the ships that crossed the North Atlantic with vital supplies for Britain; rationing had already been introduced in January 1940 as German U-boat submarines caused havoc to the merchant convoys.

Unfortunately, a British bombing raid on Brest in Brittany on 6 April 1941 damaged the Gneisenau, and so Operation Rheinübung's trio became a duo. Prinz Eugen and Bismarck, with no less a figure than Admiral Günther Lütjens (1889-1941) on board, were set to sail for the northern Atlantic via the Denmark Strait, but again the plan was scuppered when Prinz Eugen was damaged by a magnetic mine on 23 April. The Bismarck's sister ship Tirpitz was still not ready, and so it was decided to dispatch Bismarck for a temporary stay in Norway, then under German occupation. Once there, the ship was identified and its presence was communicated to British military intelligence.

Bismarck and Prinz Eugen finally set off on their mission on 19 May 1941, headed for Norway, where the latter ship refuelled. On their breakout, the ships were seen by a Swedish vessel, a Norwegian resistance spotter, and a British RAF reconnaissance plane. Once positively identified, the hunt was on to track down with ships from the British Home Fleet based at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands this highly dangerous new weapon in Germany's armoury. The British sent night bombers to the Bergen Fjords, but the German vessels had already departed for the Atlantic via the Denmark Strait earlier that day, 21 May. Already repainted grey to blend perfectly into the drab weather of the North Atlantic, now the giant identification swastikas on the deck fore and aft were painted over since the ship would be going far beyond the range of friendly aircraft.

On 22 May, the British Admiralty realised Bismarck had left Norway and so mobilised the Home Fleet. Lütjens, meanwhile, received a message that German air reconnaissance had spotted no ship movements at Scapa Flow. This intelligence was incorrect since the British had used dummy ships to give just this impression. The Royal Navy was already speeding in numbers towards Bismarck. With no fewer than eleven convoys about to cross the North Atlantic from North America, intercepting Bismarck was vital.

Sinking Hood

On 23 May, the two German ships encountered the British heavy cruisers Suffolk and Norfolk in the Denmark Strait. Bismarck opened fire on Norfolk, and the British retreated undamaged into the fog. The German pair steamed onwards at top speed, but Suffolk's new radar was able to keep track of the enemy vessels despite Lütjens' evasive manoeuvres. The Royal Navy was now on high alert, and with Bismarck pinpointed, on 24 May, the battlecruiser Hood and battleship Prince of Wales approached the German ships. Prince of Wales was so new the ship still had civilian technicians working onboard, but the big 14-inch (35.5 cm) guns were only slightly inferior to Bismarck's.

All ships opened fire. Initially, Hood fired at the Prinz Eugen, mistaking its similar lines for Bismarck. The two German ships concentrated their fire on Hood. A salvo from Bismarck fired through the thinly armoured deck of Hood and blew up a magazine, effectively splitting the ship in two almost instantaneously. Hood sank having endured just four minutes and four salvos of fire from Bismarck. From a crew of 1,420, only three survived. It was an important psychological blow since Hood was, according to Ludovic Kennedy, then serving as a sublieutenant, "the most loved ship in the Navy, the epitome of Britain and her Empire" (Ballard, 8). Kennedy likened the loss to Buckingham Palace being bombed. Prince of Wales, suffering a direct hit to the bridge from Bismarck and with half of its guns out of action, now withdrew. It was an ominous encounter. If Bismarck could cause so much damage against heavily armed and armoured ships, the destruction it could do to the convoys would be immense.

The Hunt Continues

Prinz Eugen emerged unscathed from the battle. Bismarck, though, had suffered serious damage. Two shells had caused flooding below decks, including in one of the boiler rooms. The ship was down at the bow, 1,000 tons of fuel had become inaccessible, and oil was leaking from a fuel tank. The leak made it easy for the British ships out of sight to follow Bismarck, which now left Prinz Eugen (which headed for the South Atlantic) and sailed to St Nazaire on the French coast for repairs. The ship did not have enough fuel to reach Greenland where U-boats could have come to its aid. Crucially, Bismarck could still speed at 28 knots, and all its armaments were still in good order.

Over 40 British ships, including battleships, cruisers, destroyers, and two aircraft carriers, were now on the hunt, but some were still far from the area of action, and the weather was foul. The British were using aircraft from the aircraft carrier Victorious to follow Bismarck. These Swordfish biplanes were antiquated, but each could drop a single torpedo, what the crews called a "kipper". The Swordfish attacked Bismarck on 24 May. Lütjens took evasive action by zigzagging. One torpedo struck, but the armour plating did its job. However, the blast of the torpedo knocked loose the temporary repairs made to the damage made during the battle with Hood. Again, Bismarck was taking on water.

In the dark early hours of 25 May, Lütjens circled his ship in a wide arc to come behind the pursuing British and, undetected, he sailed for St. Nazaire. Thinking the British could not possibly have lost their quarry – when, in fact, they had – Lütjens made the mistake of using his radio, which then alerted the British to where Bismarck was heading. The British ships, thanks in part to a miscalculation in coordinates, had actually been looking everywhere except where Bismarck was. It was now a race to prevent Bismarck from reaching close enough to the coast to receive U-boat protection and air cover, but Lütjens was obliged to reduce speed to save fuel; he must have bitterly rued his decision not to refuel back in Norway on 20 May.

A Catalina flying boat positively identified Bismarck on the morning of 26 May. Sensing blood, the British Admiralty was directing more and more ships to the middle of the Atlantic. In the afternoon, a squadron of 15 Swordfish from the aircraft carrier Ark Royal pursued Bismarck. The light cruiser Sheffield was the first British ship to make visual contact. The Swordfish attacked, not Bismarck, but the Sheffield in a terrible error in identification – in stormy seas a not uncommon one. Fortunately, the "kippers" had been fitted with magnetic firing pistols, and most of these failed. Sheffield escaped unscathed. The Swordfish were refuelled and rearmed with more reliable contact-firing pistols. In another quirk of war, the German U-boat U-556 was in the area and undetected; its captain spotted Ark Royal, but having already fired all his torpedoes at convoys, he could do nothing to help Bismarck.

Sink the Bismarck

The Swordfish took off from Ark Royal, and this time attacked Bismarck. All 15 planes dropped their torpedoes, flying in just 100 feet (30 m) above the waves to keep below the battleship's formidable anti-aircraft guns. Two torpedoes hit but did little damage to the armoured hull. A third "kipper" was dropped, almost missing its target but not quite; it clipped the ship's stern. It was a puny blow to a mighty ship, but it would prove a fatal one. Bismarck, with its steering mechanism damaged, could not steer out of a turn to starboard. The increasingly stormy seas with waves 50 feet (15 m) high prevented any meaningful repairs or temporary solutions to the steering problem. There was nothing left to do but face the enemy in a shoot-out. Lütjens sent the following radio signal: "Ship unmaneuvrable. We shall fight to the last shell. Long live the Führer!" (Boatner III, 328)

Five British destroyers attacked Bismarck but were driven off by the battleship's superior guns. Bismarck was temporarily lost but found again, described by Ludovic as "emerging from a distant rain squall, black, massive, beautiful, the most marvelous-looking warship that I or any of us had ever seen" (Ballard, 9). The battleship was still some 600 miles (965 km) from Brest.

At dawn on 27 May, two British battleships, King George V and Rodney, were finally in range and they opened fire on Bismarck. In support were Norfolk and, a little later, the cruiser Dorsetshire. All five ships fired their guns. One by one, Bismarck's giant turrets were blasted out of action. In the 90-minute battle, 2,876 shells were fired at the battleship, now a sitting duck and listing badly. The decision was taken to scuttle Bismarck using charges and opening the flooding valves and all watertight doors. This was a decision confirmed by two survivors (Gerhard Junack and Werner Lust) and the official German naval report (only published much later). At the same time, Dorsetshire fired two torpedoes at the burning hulk. Lütjens was dead, and Captain Lindemann deliberately stayed on board as the once-great battleship sank below the waves. Dorchester and the destroyer Maori picked up the survivors, but a sighting of a submarine (a false alarm) suspended operations, which left hundreds of men to drown. In all, 2,091 men from Bismarck died, with only 110 men surviving of the 1,000 that had jumped off the battleship when it sank. Of these 110, one man died of his wounds, the rest would spend the remainder of WWII in prisoner-of-war camps. In the evening, three German sailors who had clung to a dinghy were rescued by a U-boat, and two men on a life raft were rescued by the German ship Sachsenwald.

Aftermath

In the wider war, Bismarck was a great loss, but there was compensation that its demise had diverted a huge number of enemy ships, including many that could have assisted in the defence of Crete, which fell to a German invasion that same May of 1941. Hitler forbade the Kriegsmarine to commit large ships to Atlantic sorties, but the destruction of supply tankers and the cracking of the German naval communications code were likely more important factors in ensuring Britain continued to control the vital Atlantic sea routes.

The disappointing careers of Bismarck and Tirpitz (sunk in Norwegian waters in a bombing raid) illustrate that developments in naval warfare had made them obsolete almost before they were launched. Great battleships were simply too vulnerable to air attack to justify the tremendous cost that went into building them.

The Bismarck Wreck

Bismarck continued to gain attention after the war. Two notable books by men involved were Pursuit: The Chase and Sinking of the Bismarck by Ludovic Kennedy and Battleship Bismarck by Burkard von Müllenheim-Rechberg. A British film, Sink the Bismarck!, was released in 1960. Then, in the 1980s, the hunt began to find Bismarck.

Robert D. Ballard (b. 1942) had discovered the wreck of RMS Titanic in 1985, now, four years later, he led a team to find Bismarck. After a two-year search, the wreck was finally discovered in June 1989. The great battleship was sitting on its keel in one piece 3 miles (4.8 km) below the surface of the Atlantic. The mighty gun placements were empty, but the ship still possessed an aura of bulk and power. Investigation of the condition of the wreck has suggested that the battleship was already fast on its way to sinking even before it was scuttled, but the German charges allowed so much water into the ship that it remained remarkably intact during its long descent to its final resting place on the seabed.