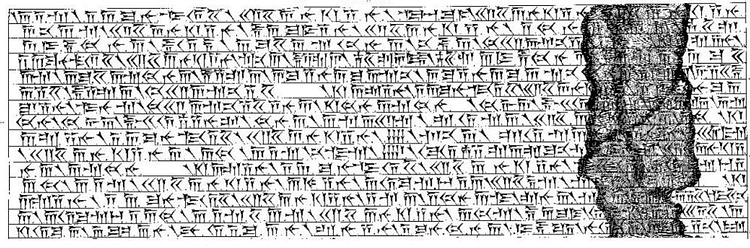

The Behistun Inscription is a relief with accompanying text carved 330 feet (100 meters) up a cliff in Kermanshah Province, Western Iran. The work tells the story of the victory of the Persian king Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE) over his rebellious satraps when he took the throne of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE) in 522 BCE.

The relief is accompanied by text in three languages – Old Persian, Elamite, and Akkadian – relating Darius I's autobiography, authority to rule by divine grace, and triumph over those who opposed his rise to power. It was commissioned at some point after he had suppressed the revolts (c. 520 BCE) though when it was completed is unknown.

The relief measures 82 feet (25 meters) long and 49 feet (15 meters) high, with the text written in columns above a scene in which Darius I, followed by two escorts, tramples on the body of the king he overthrew and faces a line of nine prisoners (the main satraps who had rebelled against him) bound and led by a rope. The figure of Darius I appears to be looking upward at the image of the Faravahar, a Persian symbol of divinity (depicting a royal male figure seated on a winged disc) which, in this case, represents the supreme god Ahura Mazda.

The relief is generally accepted as having been inspired by a much older, and very similar, relief in the same area (still extant), the Sar-e Pol-e Zahab Relief (also known as the Sarpol-i Zohab Relief and Anubanini Rock Relief), which depicts King Anubanini of the Kingdom of Lullubi (r. c. 2300 BCE) in similar pose, defeating his enemies, and giving thanks to his gods, especially the goddess of war, Ishtar.

The relief was first noted by Europeans in the 18th century CE and was famously copied by the scholar Sir Henry C. Rawlinson (l. 1810-1895 CE) in 1835 and 1843 CE. Rawlinson's copy of the three cuneiform texts enabled him, and other notable scholars of the time, to decipher them since, once Old Persian cuneiform was understood, the cuneiform of the Elamites and Akkadians could be as well. The Behistun Inscription thus became the means whereby scholars could translate Near Eastern languages. The relief can still be seen today and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2006 CE.

Rise of Darius the Great

Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) founded the Achaemenid Empire and, upon his death, was succeeded by his son Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE). Cambyses II embarked on a campaign to conquer Egypt and, while he was there, someone else (allegedly his brother Bardiya, also known as Smerdis) usurped the throne and proclaimed himself king. The usurper was not actually Bardiya, however, because Cambyses had murdered Bardiya before leaving for Egypt in order to prevent this very situation. The new king was actually a Bardiya look-alike named Gaumata (r. 522 BCE), one of the magi (priestly class) of the court.

Cambyses II was returning from Egypt to deal with the problem when he died - allegedly of a self-inflicted wound - and Darius I, a distant cousin who was among Cambyses II's entourage, took it upon himself – with the aid of co-conspirators – to assassinate the usurper and proclaim himself king. As a relative of the late Cambyses II, Darius claimed legitimacy because the usurper was not a member of the royal family. His legitimacy was proven by his victory over his enemies, demonstrating that the supreme god Ahura Mazda was on his side and approved of his actions.

This account comes from Darius I himself in the Behistun Inscription, but the truth of it has been challenged by a number of modern-day scholars. It has been suggested that the so-called “usurper” was, in fact, Cambyses II's younger brother Bardiya/Smerdis who either took the throne in his brother's absence without permission or was placed in charge by him and then overstepped his authority. The satraps (provincial governors) of the empire seem to have accepted Bardiya's reign as legitimate while, when Darius I returned and assassinated him, at least 19 provinces rose in revolt. The story of Cambyses II killing his brother before leaving for Egypt only comes from Darius I, and he would have had to make such a claim in order to establish legitimacy: he had not, he claims, killed the rightful king but an imposter and usurper.

The Behistun Text

As noted, the text of the relief was engraved on the cliff-face in three languages. The Old Persian inscription consists of 414 lines in five columns; the Elamite of 593 lines in eight columns; the Akkadian of 112 lines. The following is a translation of Column I of the Old Persian text by one Herbert Cushing Tolman of Vanderbilt University, USA, from 1908 CE. The other columns are summarized following Column I, but the full text, provided online by Bruce J. Butterfield, appears in the bibliography following this article.

Column I

[1.1] I (am) Darius, the great king, the king of kings, the king in Persia, the king of countries, the son of Hystaspes, the grandson of Arsames, the Achaemenide.

[1.2] Says Darius the king: My father (is) Hystaspes, the father of Hystaspes (is) Arsames, the father of Arsames (is) Ariaramnes, the father of Ariaramnes (is Teispes), the father of Teispes (is) Achaemenes.

[1.3] Says Darius the king: Therefore, we are called the Achaemenides; from long ago we have extended; from long ago our family have been kings.

[1.4] Says Darius the king: 8 of my family (there were) who were formerly kings; I am the ninth (9); long aforetime we were (lit. are) kings.

[1.5] Says Darius the king: By the grace of Auramazda I am king; Auramazda gave me the kingdom.

[1.6] Says Darius the king: These are the countries which came to me; by the grace of Auramazda I became king of them; Persia, Susiana, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, the (lands) which are on the sea, Sparda, Ionia, [Media], Armenia, Cappadocia, Parthia, Drangiana, Aria, Chorasmia, Bactria, Sogdiana, Ga(n)dara, Scythia, Sattagydia, Arachosia, Maka; in all (there are) 23 countries.

[1.7] Says Darius the king: These (are) the countries which came to me; by the grace of Auramazda they became subject to me; they bore tribute to me; what was commanded to them by me this was done night and (lit. or) day.

[1.8] Says Darius the king: Within these countries what man was watchful, him who should be well esteemed I esteemed; who was an enemy, him who should be well punished I punished; by the grace of Auramazda these countries respected my laws; as it was commanded by me to them, so it was done.

[1.9] Says Darius the king: Auramazda gave me this kingdom; Auramazda bore me aid until I obtained this kingdom; by the grace of Auramazda I hold this kingdom.

[1.10] Says Darius the king: This (is) what (was) done by me after that I became king; Cambyses by name, the son of Cyrus (was) of our family; he was king here; of this Cambyses there was a brother Bardiya (i. e. Smerdis) by name possessing a common mother and the same father with Cambyses; afterwards Cambyses slew that Bardiya; when Cambyses slew Bardiya, it was not known to the people that Bardiya was slain; afterwards Cambyses went to Egypt; when Cambyses went to Egypt, after that the people became hostile; after that there was Deceit to a great extent in the provinces, both in Persia and in Media and in the other provinces.

[1.11] Says Darius the king: Afterwards there was one man, a Magian, Gaumata by name; he rose up from Paishiyauvada; there (is) a mountain Arakadrish by name; from there - 14 days in the month Viyakhna were in course when he rose up; he thus deceived the people [saying) “I am Bardiya the son of Cyrus brother of Cambyses”; afterwards all the people became estranged from Cambyses (and) went over to him, both Persia and Media and the other provinces; he seized the kingdom; 9 days in the month Garmapada were in course - he thus seized the kingdom; afterwards Cambyses died by a self-imposed death.

[1.12] Says Darius the king: This kingdom which Gaumata the Magian took from Cambyses, this kingdom from long ago was (the possession) of our family; afterwards Gaumata the Magian took from Cambyses both Persia and Media and the other provinces; he seized (the power) and made it his own possession; he became king.

[1.13] Says Darius the king: There was not a man neither a Persian nor a Median nor any one of our family who could make Gaumata the Magian deprived of the kingdom; the people feared his tyranny; (they feared) he would slay the many who knew Bardiya formerly; for this reason he would slay the people; "that they might not know me that I am not Bardiya the son of Cyrus;" any one did not dare to say anything against Gaumata the Magian until I came; afterwards I asked Auramazda for help; Auramazda bore me aid; 10 days in the month Bagayadish were in course I thus with few men slew that Gaumata the Magian and what men were his foremost allies; there (is) a stronghold Sikayauvatish by name; there is a province in Media, Nisaya by name; here I smote him; I took the kingdom from him; by the grace of Auramazda I became king; Auramazda gave me the kingdom.

[1.14] Says Darius the king: The kingdom which was taken away from our family, this I put in (its) place; I established it on (its) foundation; as (it was) formerly so I made it; the sanctuaries which Gaumata the Magian destroyed I restored; for the people the revenue(?) and the personal property and the estates and the royal residences which Gaumata the Magian took from them (I restored); I established the state on (its) foundation, both Persia and Media and the other provinces; as (it was) formerly, so I brought back what (had been) taken away; by the grace of Auramazda this I did; I labored that our royal house I might establish in (its) place; as (it was) formerly, so (I made it); I labored by the grace of Auramazda that Gaumata the Magian might not take away our royal house.

[1.15] Says Darius the king: This (is) what I did, after that I became king.

[1.16] Says Darius the king: When I slew Gaumata the Magian, afterwards there (was) one man Atrina by name, the son of Upadara(n)ma; he rose up in Susiana; thus he said to the people; I am king in Susiana; afterwards the people of Susiana became rebellious (and) went over to that Atrina; he became king in Susiana; and there (was) one man a Babylonian Nidintu-Bel by name, the son of Aniri', he rose up in Babylon; thus he deceived the people; I am Nebuchadrezzar the son of Nabu-na'id; afterwards the whole of the Babylonian state went over to that Nidintu-Bel; Babylon became rebellious; the kingdom in Babylon he seized.

[1.17] Says Darius the king: Afterwards I sent forth (my army) to Susiana; this Atrina was led to me bound; I slew him.

[1.18] Says Darius the king: Afterwards I went to Babylon against that Nidintu-Bel who called himself Nebuchadrezzar; the army of Nidintu-Bel held the Tigris; there he halted and thereby was a flotilla; afterwards I placed my army on floats of skins; one part I set on camels, for the other I brought horses; Auramazda bore me aid; by the grace of Auramazda we crossed the Tigris; there the army of Nidintu-Bel I smote utterly; 26 days in the month Atriyadiya were in course - we thus engaged in battle.

[1.19] Says Darius the king: Afterwards I went to Babylon; when I had not [yet] reached Babylon - there (is) a town Zazana by name along the Euphrates - there this Nidintu-Bel who called himself Nebuchadrezzar went with his army against me to engage in battle; afterwards we engaged in battle; Auramazda bore me aid; by the grace of Auramazda the army of Nidintu-Bel I smote utterly; the enemy were driven into the water; the water bore them away; 2 days in the month Anamaka were in course - we thus engaged in battle.

Columns II and III continue the list of satrapies which rebelled and how Darius I put down the revolts and killed the leaders. Column IV begins by repeating the account of Darius I's victory over Gaumata and then appeals to the reader to accept his version of what happened, insists his actions and subsequent reign are in accord with the wishes of Ahura Mazda, and warns any who would deface or destroy his inscription of the wrath they will face from the supreme god. Column V relates a final battle and concludes with a line thanking Ahura Mazda.

Interpretations

Whether Darius I is telling the truth in his inscription cannot finally be known in spite of various modern-day scholars' assertions otherwise. The famous scholar of Persian history, A. T. Olmstead, claims without doubt that Darius I was the actual usurper and Bardiya/Smerdis the rightful king based primarily on how there is no evidence of unrest or rebellion under Bardiya's rule but widespread revolt when Darius I takes power.

According to this view, the Behistun Inscription would fall into the genre of Mesopotamian Naru Literature in which a certain historical event (or king) is presented in a tale with fictional elements to achieve a certain end - not to deceive, but to enlighten or give reason to events and encourage some central cultural value (in this case, the divine grace which legitimized a king). The Akkadian monarch Sargon of Akkad (r. 2334-2279 BCE), legendary by the time of Darius I, had used the same technique in his own autobiography centuries before in presenting himself as a man of the people to win support.

Olmstead, and others, could well be right, but it is just as likely that the satraps revolted, one after the other, in a bid to establish themselves as the rightful king – just as Darius I claims they did – whether the man Darius I overthrew was the “real” Bardiya or the usurper Gaumata. The subject nation states of any empire, from the Akkadian through the Roman Empire, took advantage of a change in monarchs to assert their rights in greater or lesser degrees, whether by diplomatic requests or outright rebellion. It is hardly unusual to find subjugated peoples, no matter how well they are treated, wanting their freedom and asserting their desire for self-determination through rebellion.

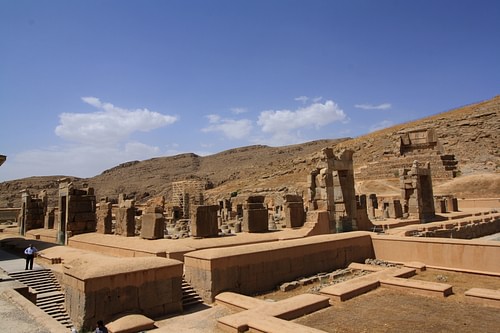

What kind of monarch Bardiya/Gaumata would have been will never be known but Darius I is not known as “the Great” for nothing. He initiated grand building projects (such as his complex at Persepolis), commissioned roads throughout the empire (including the great Royal Road from Persepolis to Sardis), invented the postal system, standardized the currency through introduction of his own coinage (the Daric), increased and organized trade (building a canal in Egypt linking the Nile River to the Red Sea for this purpose), and continued the Persian government policies of his predecessors of tolerance and acceptance of the religious and cultural values of all the subject nations in his empire. In every respect, Darius I was an impressive king and, finally, whether he embellished his autobiography does not matter; he proved he was the legitimate ruler through his exemplary reign.

Discovery & Significance

Although the Behistun Inscription had been noted earlier by other Europeans, who also made copies of the Old Persian text, the first to make major efforts in understanding the piece was Rawlinson in 1835 CE when he was serving in Iran with the British East India Company's forces. Although Darius I makes it clear in the work that he wanted people to read his words, and even though he placed them on a well-traveled road between Babylon and Ecbatana (two of the major administrative centers of the empire), he placed them so high on the cliff that no one on the road would have been able to read the inscriptions or see the images clearly. Further, once the relief was carved and the inscriptions complete, he had the ledge the workers had stood on removed so no one could get close enough to deface the work. Removal of the ledge, however, also meant no one could get close enough to read it.

In order to copy the inscription, Rawlinson enlisted the help of a local youth and, together, they carried up and lay planks across the cliff-face so Rawlinson could write down the Old Persian text. He then went to work translating it, relying on previous efforts by the German explorer Karsten Niebuhr (l. 1733-1815 CE) who had first publicized the existence of the site after his visit in 1764 CE, and the later work of Georg Friedrich Grotefend (l. 1775-1853 CE) who built on Niebuhr's efforts. In 1843 CE, Rawlinson returned and managed to copy the Elamite and Akkadian inscriptions, again with the help of a local youth, through the use of ropes suspending him from the cliff.

Afterwards, working with the brilliant Assyriologists Reverend Edward Hicks (l. 1792-1866 CE), Edwin Norris (l. 1795-1872 CE), Julius Oppert (l. 1825-1905 CE), and William Henry Fox Talbot (l. 1800-1877 CE), the inscriptions were fully translated, using the Old Persian as the basis for understanding the other two. The Behistun Inscription thus became, for Orientalists and Assyriologists, what the Rosetta Stone was for Egyptologists in unlocking the languages of the ancient Near Eastern civilizations. This discovery followed the work of George Smith (l. 1840-1876 CE) who had earlier translated Mesopotamian cuneiform and, taken together, opened up the impressive cultures of the Near East to the modern world.