Benedict Arnold (1741-1801) was a general of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). He was considered one of the finest Patriot military officers during the early years of the conflict but defected to the British in 1780 after being repeatedly passed over for promotion. Today, the phrase 'Benedict Arnold' remains a colloquialism for 'traitor' in the U.S.

Early Life & Family

The future Revolutionary War general was the scion of a noteworthy New England family. His great-grandfather, the first Benedict Arnold, had served as colonial governor of Rhode Island for 15 years. During his tenure, New England was ravaged by the destructive King Philip's War (1675-1678), and Governor Arnold spent his final years aiding in Rhode Island's recovery. In 1730, the governor's grandson and namesake, the third Benedict Arnold, emigrated to Norwich, Connecticut, to seek his fortune; he soon became a prosperous merchant and successful sea captain. In 1733, Captain Arnold married the widowed Hannah Waterman King, with whom he would ultimately have six children. Only two of these children would live to adulthood: a son, the fourth Benedict, and a daughter, Hannah (b. 1742).

Benedict Arnold (the future general) was born on 14 January 1741 in Norwich. The success of his father's business meant that Arnold's childhood was comfortable. Robust and athletic, the young Arnold spent his free time ice skating upon Connecticut's frozen lakes and leading the local boys in mischievous stunts such as leaping over loaded wagons that were driving down the main street or setting fire to a barrel of tar atop the town's hill. Alongside these episodes of recklessness, Arnold showed an aptitude for writing. At the age of ten, his mother enrolled him at a private school in Canterbury, with hopes that he would go on to be educated at Yale College.

It was not to be. By the early 1750s, Captain Arnold's fortunes had begun to decline; he had overextended his business and was now faced with staggering debt. Captain Arnold slipped into alcoholism and eventually lost his business altogether. No longer able to pay for their son's education, the Arnolds pulled young Benedict out of private school and instead apprenticed him to his mother's cousin, an apothecary named Dr. Lathrop. Arnold proved a dutiful apprentice but nevertheless yearned for adventure. The outbreak of the French and Indian War (1754-1763) would give him an opportunity, and, in 1757, he obtained Dr. Lathrop's permission to join the Norwich militia to help defend Fort William Henry from French and Native American attack. The Norwich militia had barely begun its march, however, when it learned that the fort had already fallen; their mission now pointless, the militia disbanded and went home.

Still thirsting for adventure, Arnold ran away the following year to join a New York militia stationed outside Albany. He showed promise and impressed his fellow militiamen with his excellent marksmanship and ability to march for hours without tiring. But before he could see any action, Arnold received news that his mother was dangerously ill; he deserted to return to Norwich and was by her side when she died on 15 August 1758. The death of his wife only sent Captain Arnold spiraling further into alcoholism. He was arrested in 1761 for public drunkenness and died the next year. Arnold was left with the funeral expenses of both his parents.

Merchant & Son of Liberty

In 1762, Arnold came of age and was loaned £500 by Dr. Lathrop to start his own business. He moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where he established himself as a bookseller and pharmacist. Arnold found quick success and, by 1763, had made enough money to purchase a 40-ton sloop, the Fortune. He satisfied his urge for adventure by sailing the Fortune to Canada and the West Indies, trading lumber and livestock for various goods; his sister Hannah managed the West Haven shop while he was at sea. But despite his success, Arnold was still as reckless as he had been in his youth. While anchored in Honduras, Arnold fought a duel with a British sea captain who had insulted his manners. During the first round, the captain missed his shot, while Arnold's own shot grazed the captain's arm. Arnold then coldly warned the captain that if he missed his second shot, "I shall kill you" (Randall, 45). The captain quickly apologized.

Like many of his fellow colonial merchants, Arnold was involved in the smuggling of molasses from the West Indies; since the commodity was vital to the economies of the New England colonies, its smuggling was considered a victimless crime, and officials often turned a blind eye in exchange for a bribe. But, in 1764, the British Parliament passed the Sugar Act, which severely cracked down on colonial smuggling, negatively effecting many merchants' businesses. In 1766, one of Arnold's former sailors fell out with him over a payment dispute and threatened to inform British officials about his smuggling activities. In retaliation, Arnold and a gang of New Haven men accosted the sailor, beating him up and lashing him 40 times upon the back. Arnold was arrested but, because New England courts typically sided with smugglers against British officials, he was fined only 50 shillings, a light punishment.

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act, which taxed the colonists for all paper documents including legal contracts, newspapers, and calendars. This outraged many Americans, who believed that taxation without representation was unconstitutional. Arnold, too, was outraged; by this point, he had run up a debt of around £16,000, and he feared that the new Parliamentary taxes would further damage his finances. He joined the Connecticut chapter of the Sons of Liberty, a loose organization of political agitators who opposed Parliament's taxes and often resorted to riots. Arnold likely participated in one such riot in September 1765, in which the Sons of Liberty surrounded the New Haven home of the local stamp distributor, James Ingersoll, threatening to pull it down unless he resigned; Ingersoll relented and promised the crowd he would not execute his office. Arnold continued to involve himself with the Sons of Liberty, partaking in the group's acts of violence, which included the tarring and feathering of Loyalists.

On 22 February 1767, Arnold married the 22-year-old Margaret Mansfield, daughter of the New Haven sheriff. She was a beautiful, albeit painfully shy, young woman, and Arnold's letters suggest that he married her out of love rather than any monetary consideration. The couple would have three sons: Benedict (b. 1768), Richard (b. 1769), and Henry (b. 1772). However, the marriage would soon turn cold; Arnold's copious amounts of debt and his long absences at sea left Margaret feeling depressed. Arnold hoped to revive their relationship, often writing affectionate letters to Margaret from sea, and involving her father in his business. Matters were likely not helped by Arnold's sister, who lived with the couple and dominated household affairs.

Patriot General

Arnold was at sea in June 1770, when he first received news of the Boston Massacre. He vented his outrage in a letter:

Good God! Are Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their glorious liberties, or are they all turned philosophers that they don't take vengeance upon such miscreants? I am afraid of the latter and that we shall soon see ourselves as poor and as much oppressed as ever heathen philosopher was.

(Randall, 68)

Arnold would soon find out that his fellow Americans were far from asleep. In 1774, after Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts, militias from across New England began preparing for war. Arnold was elected captain of the New Haven militia in March 1775 and spent over a month drilling them. After the first shots of the war were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord (19 April 1775), Arnold eagerly led his militia to join the nascent Continental Army at its headquarters in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Upon learning that the Patriot forces lacked adequate arms and ammunition, Arnold suggested that they seize the munitions at Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain and volunteered to lead the expedition himself. The Massachusetts Provincial Congress accepted his offer, granting him the rank of colonel.

Arnold raced to Castleton, New York, where he linked up with Ethan Allen and the Green Mountain Boys, who were already on their way to seize Fort Ticonderoga. After a brief leadership dispute, Arnold and Allen agreed to share command. On 10 May 1775, they surprised the fort's garrison as it slept and secured the capture of Fort Ticonderoga without spilling a drop of blood. Once Allen and the Green Mountain Boys had gone home, Arnold expected to be given command of Ticonderoga and the surrounding forts; he was dismayed, therefore, when Colonel Benjamin Hinman arrived to take command in June, with Arnold relegated to Hinman's second-in-command. Arnold felt slighted and opted to resign rather than serve under Hinman, who he felt was undeserving of the command. On his way back to Cambridge, he received the tragic news that his wife Margaret had died.

Arnold was still determined to make a name for himself. Back at Cambridge, he convinced the new commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, George Washington, to allow him to lead a secondary expedition through the Maine wilderness in support of General Richard Montgomery, who was leading the American invasion of Quebec. Once again commissioned as a colonel, Arnold was given command of 1,100 men and landed at the mouth of the Kennebec River in September 1775. The expedition then embarked on a harrowing, 350-mile (563 km) trek through the Maine wilderness, which included sailing up the Dead River in leaky boats. Most of their food spoiled, and a month into the expedition, around 450 men had deserted, with another 55 having died. Arnold pressed on with his remaining men, and on 9 November, they finally reached the city of Quebec. After linking up with the main army under General Montgomery, they assaulted the city during a blizzard on 31 December. The Patriots, however, were defeated; Montgomery was killed, and Arnold was wounded in the left leg.

Arnold was promoted to brigadier general for his role in the Battle of Quebec. He took command of the remnants of the army and maintained a half-hearted siege of the city until April 1776, when he was relieved by General David Wooster. Arnold was then appointed military governor of Montreal, which had been captured by Montgomery the year before, and oversaw the evacuation of American troops from the city as British reinforcements drew closer. Realizing he had to defend the fledgling United States from a British counter-invasion, Arnold directed the construction of a fleet on Lake Champlain. When the British attack finally came, Arnold's fleet was ready to resist them at the Battle of Valcour Island (11 October 1776). Though the Patriots were once again defeated, Arnold's actions halted a British invasion of New York until the next year.

Disgruntled War Hero

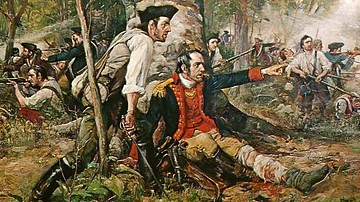

During the winter of 1776, Arnold was assigned to oversee the defense of Rhode Island. While fulfilling this role, he learned in February 1777 that Congress had passed him over for promotion to major general, instead promoting five officers considered junior to him. Enraged, Arnold threatened to resign but was persuaded against doing so by Washington. He remained in New Haven, where he was "sulking in his tent like some rustic Achilles" (quoted in Boatner, 27), when he received word of an impending British raid on Danbury, Connecticut, in April 1777. Arnold leaped into action, leading Patriot militia against the British at the Battle of Ridgefield (27 April), where he was once again wounded in the leg. For this action, he was finally promoted to major general, although he was not given seniority over the five officers who had passed over him.

That summer, Arnold was assigned to the Northern Department of the Continental Army, to help defend against a British expedition moving south from Canada. In August 1777, he was sent to relieve the siege of Fort Stanwix, which he accomplished through deception; using an Indigenous messenger, he was able to convince the British commander, Colonel St. Leger, that his force was larger than it was, scaring St. Leger into abandoning the siege and retreating into Canada. Arnold then played vital roles in both of the Battles of Saratoga (19 September; 7 October 1777). In the lull between the two engagements, Arnold and his superior officer, General Horatio Gates, got into a heated argument after Gates neglected to inform Congress about Arnold's role in the first battle; the argument devolved into a shouting match, and Gates removed Arnold from command. Arnold nevertheless remained in the American camp and participated in the Second Battle of Saratoga; while leading a spirited assault on the British redoubts, he was wounded yet again in the left leg.

In 1778, while Arnold was recovering from his wound, he was appointed military governor of Philadelphia; it was in this position that he ultimately decided to betray his country. Philadelphia had recently been occupied by the British and still housed families with Loyalist sympathies. In early 1779, Arnold married the daughter of one such family, the beautiful 19-year-old Peggy Shippen, who was herself a Loyalist and had several contacts in the British army. Additionally, Arnold used his position as military governor to profit off the sale of war supplies, a move that earned him the enmity of several Philadelphia politicians; one such politician made the prophetic observation that "money is [Arnold's] god, and to get enough of it he would sacrifice his country" (Boatner, 27). In 1779, the politicians court-martialed Arnold for his war profiteering. Though Arnold was acquitted of all but two of the charges, he still felt embittered that he had been court-martialed at all.

Arnold's Treason

In early May 1779, Arnold offered his services to Sir Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British army, and soon began regular, encoded correspondences with Clinton's aid, Major John André. While the precise reasons for his doing so are still a matter of speculation, he likely felt insulted by Congress' constant refusals to promote him despite his self-perceived military heroism; his constant feuds with other Patriot generals and his court-martial only further alienated him from the United States. Further, his perpetual debt left him in need of money, which the nearly bankrupt Congress seemed unlikely to provide. Finally, if Arnold had been toying with the idea of defection prior to meeting Peggy Shippen, his marriage to her probably pushed him over the edge.

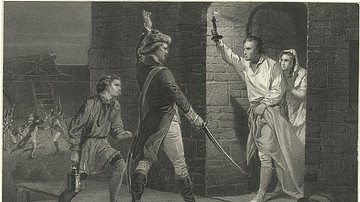

Arnold corresponded with Major André for 16 months, suggesting various ways in which he could help the British cause. Then, on 3 August 1780, Arnold was appointed commander of West Point, a stronghold that controlled the strategically valuable Hudson River Valley in New York. Arnold proposed to hand West Point over to the British in exchange for £20,000. The British accepted, and Arnold set about systematically weakening West Point's fortifications while transferring his personal assets to London. On 21 September, Arnold and André met in person to discuss the details of their plot; two days later, André was captured on his way back to British lines, and the conspiracy was exposed. Arnold escaped aboard a British vessel, abandoning André to be hanged by the Patriots. Once safely in British-occupied New York City, Arnold penned an essay To the Inhabitants of America, in which he attempted to justify his actions.

Arnold's abandonment of André earned him the scorn of British officers; Clinton, in particular, disliked and distrusted Arnold but nevertheless commissioned him as a brigadier general in the British army. In December 1780, Arnold led a small army of 1,600 British troops into Virginia. He captured Virginia's capital, Richmond, and raided the surrounding countryside, pillaging and burning American towns. Washington sent an army under Marquis de Lafayette in pursuit; Lafayette was ordered to hang Arnold as a traitor should he capture him. But in May 1781, Arnold was relieved from his command. Shortly thereafter, a Franco-American army won the Siege of Yorktown, all but guaranteeing the United States' independence. Arnold had gambled on the wrong side.

Later Life

In December 1781, Arnold moved to London with his family. He secured an audience with King George III of Great Britain, who wished to consult Arnold on American affairs, but this was the extent of his post-war service to Britain. Arnold was hated on both sides of the Atlantic; while the cause of the American disdain for him was obvious, on the British side, he was considered an unprincipled mercenary who had betrayed his countrymen for money and cowardly abandoned Major André. Arnold applied for several jobs in government and in the British East India Company but was rejected each time. He pursued several business ventures, speculating in land in Canada and rekindling his trading business in the West Indies, but was unable to shake off his stained reputation; in 1792, he fought a bloodless duel with the Earl of Lauderdale, after the earl had besmirched his reputation before the House of Lords.

Debilitated by gout, Arnold's health declined throughout the 1790s until, in early 1801, he was diagnosed with dropsy. He died in London on 14 June 1801 at the age of 60; according to legend, he died in his American military uniform, uttering his final words: "Let me die in this old uniform in which I fought my battles. May God forgive me for having put on another" (Shattuck). Today, Benedict Arnold remains one of the most infamous turncoats in American history, whose very name has become synonymous with 'traitor'.