Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571 CE) was an Italian Renaissance sculptor, medallist, and goldsmith whose most famous works today include the bronze statue of Perseus holding the head of Medusa, which now stands in Florence, and a magnificent gold salt cellar made for Francis I of France (r. 1515-1547 CE), now in Vienna. Although the surviving body of Cellini's work is surprisingly small, he remains one of the best-known Renaissance artists thanks to his colourful autobiography, written around 1558 CE.

Life & Works

Benvenuto Cellini was born in Florence in 1500 CE, the son of a stonemason. Benvenuto's father had hoped he would also train to become a mason, perhaps to become a woodwind player, too. Benvenuto loved drawing, though, and his creative vent found an outlet in metalwork. Cellini began his career as an apprentice in a goldsmith's workshop in Florence. In 1519 CE the young craftsman moved on to Rome, working in the mint there, and he remained in the Eternal City until 1540 CE. While Rome was his base, there were short spells spent working in Florence and Venice. Perhaps in the latter city, he came across Islamic art as Cellini often used 'arabesque' motifs in his metalwork engravings.

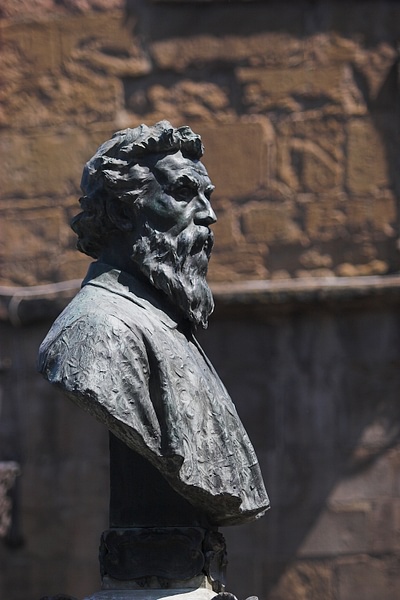

Cellini moved to France in 1540 CE and remained there for the next five years. He made various works of art for the French king Francis I, including his famous salt cellar and the bronze plaque of Diana (see below). Back in Florence for good from 1545 CE, the artist worked on several commissions from Cosimo I de' Medici, then Duke of Florence (ruled 1537-1569 CE). One project was the statue of Perseus (see below) and Cellini also did an idealised bronze portrait bust of the duke. The bust has Cosimo fetchingly dressed in armour as Roman emperors were wont to wear for their portraits. An interesting detail is the roaring lion on Cosimo's right shoulder, a reference to his prowess as a political leader as the lion or marzocco was a potent symbol throughout the history of Florence. The bust once had gilt highlights and enamel eyes. Curiously, Cosimo sent the bust to Elba after he conquered that island in 1557 CE. It measures an impressive 1.1 metres (3 ft 7 in) in height, and today it is back more or less where it was made, residing in the Bargello Museum in Florence.

Another bronze portrait bust was commissioned by the banker Bindo Altoviti (1491-1557 CE). Finally, Cellini produced a life-size representation of Jesus Christ on the Cross (c. 1562 CE), which was perhaps originally intended for the sculptor's own tomb but which now resides in the San Lorenzo Monastery, El Escorial, Spain. Cellini died in May 1571 CE, and he was buried in the Basilica of the Most Holy Annunciation in Florence.

For such a famous artist and for one who we know so much about personally, the works which can be positively identified as by the hand of Cellini are surprisingly few. There are merely seven sculptures, seven coins, three medals, two seals, and one salt cellar.

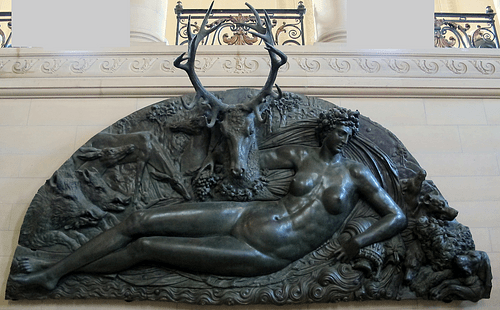

The Nymph of Fontainebleau

Commissioned by Francis I, the Nymph of Fontainebleau is a larger-than-lifesize bronze plaque showing a reclining Diana from Greek/Roman mythology. Diana was a huntress and so an ideal subject for the French king who was a passionate hunter of forest game. The nude goddess has a massive stag with huge antlers looking over her shoulder while at the sides of the piece are deer, wild boars, and hunting dogs. The sculpture was originally meant to sit above the entrance gate of the Palace of Fontainebleau, hence its misleading name, but the king never got around to having it installed. When Henry II of France became king (r. 1547-1559 CE), he decided the sculpture was more suitable for a hunting lodge and so gave it to his mistress Diane de Poitiers (1499-1566 CE) for her home, the Chateau d'Anet, south of Paris. Today, the sculpture is in the Louvre museum in Paris.

The Gold Salt Cellar

The finest example of Cellini's skills as a goldsmith is the salt cellar he made for Francis I, in the early 1540s CE. Made using enamel and gold set on an ebony base it has two reclining nude figures at the top. The female figure either represents the Roman mother goddess Tellus, symbolising the earth, or Ceres, the goddess of agriculture. Next to her, the miniature temple was designed to hold pepper. The male figure is the Greek/Roman god Poseidon/Neptune, who holds a trident and, of course, he represents the sea. The boat next to him was intended to be filled with salt. The two figures have their legs intertwined, suggesting the mutual interdependence of these two spheres of human existence (Campbell, 350), as well as the frequent coupling of these two bounties of the earth and sea on the aristocratic dinner plate: salt and pepper. The base of the cellar is decorated with figures variously representing the Hours, the Winds, and human activities. The salt cellar was later given by King Charles IX of France (r. 1560-1574 CE) as a wedding present to Archduke Ferdinand of Tyrol, which explains why the piece has ultimately found its way to its present location, the Kunsthistorisches Museum of Vienna.

The Perseus Statue

Cellini's signature work is a bronze statue of Perseus, the hero from Greek mythology, made between 1545 and 1554 CE. The figure was commissioned by Cosimo I and it was an opportunity for Cellini to show that his stint abroad had not diminished his position as one of the city's foremost artists. The completed figure is larger than lifesize and stands 3.2 metres (10 ft 6 in) tall on an intricately carved pedestal.

Perseus has just cut off the head of the dreadful gorgon Medusa, whose stare turned living creatures into stone. The corpse of Medusa is shown being trampled on by the hero who wields a mighty sword while looking suitably disdainful of his foe. Cellini has boldly added his name to the piece, written on the ribbon across the hero's chest. The statue today stands in the Loggia della Signoria (aka Loggia dei Lanzi) in Florence, exactly where it was originally intended to stand and so display the erudition and wealth of the Medici family to the people of the dukedom. Renaissance art was rarely commissioned for its aesthetic appeal alone, and Cosimo de' Medici knew full well that the Florentines would see in the hero vanquishing a fearsome enemy a reflection of the Medici's success as rulers battling rival cities and states.

The Autobiography

Cellini, like several other noted Renaissance artists, used the written word to pass on his experience and opinions regarding his craft. He wrote a treatise on sculpture, for example, and this gives all kinds of practical advice for artists ranging from how to cast bronze sculpture correctly to how to make the best plaster for moulds by mixing gesso with ground ox horn and rinsed horse manure.

Around 1558 CE Cellini extended these works to a full autobiography, not the first by a European artist but perhaps one of the most exaggerated. In this never-completed work, the artist claims, for example, to have killed the Duke of Bourbon during the 1527 CE Sack of Rome by rebels from the army of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (r. 1519-1556 CE). Despite these boasts, the work does contain some frank assessments, and Cellini was an eyewitness to the events in Rome. The sculptor was even involved in melting down papal treasures in preparation for an evacuation of the Vatican Palace.

Other interesting events in the artist's life include his time in Rome where he was once put in prison accused of stealing some of the Pope's jewels. Delighting in breaking society's conventions, the artist would go to parties with one of his male workshop assistants dressed as a woman or push the boundaries of good artistic taste by entirely gilding one of his followers. The autobiography reveals a fiercely independent character and a keen learner, someone who frequently found himself in fights, enjoyed fine food, and had a promiscuous sex life with both men and women. There is here, too, a man who possessed a genuine concern with presenting to the world what it means to be an artist and what it takes to produce great art.

A complex character whose best work has not survived for us to admire, the famed Renaissance historian Jacob Burckhardt gives the following summary of Cellini's character, as revealed in his autobiography:

Benvenuto as a man will interest mankind to the end of time. It does not spoil the impression when the reader often detects him bragging or lying; the stamp of a mighty, energetic and thoroughly developed nature remains. By his side our modern autobiographies, though their tendency and moral character may stand much higher, appear incomplete beings. He is a man who can do all and dares do all, and who carries the measure in himself. Whether we like him or not, he lives, such as he was, as a significant type of the modern spirit. (217).