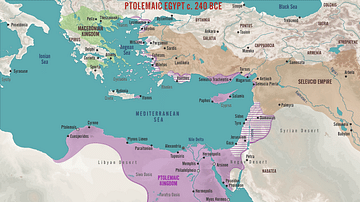

Berenice II Euergetis (c. 267-221 BCE) was a pre-eminent Hellenistic queen, who ruled together with her husband Ptolemy III (r. 246-221 BCE), when the Ptolemaic kingdom was at the height of its power, dominating most of the eastern Mediterranean. Even before her marriage to Ptolemy III, she showed herself an assertive young woman in Cyrene, her native city. In Alexandria she acted as regent in her husband's absence and directed a religious procession – as a result of which one of the canonical constellations was named after her. Her epithet, Euergetis, designates her as “benefactress” in gratitude for her generosity. Berenice was thus queen at an important juncture in Hellenistic history and one of the defining figures of Hellenistic queenship.

Berenice, the daughter of the Macedonian dynast Magas and his Seleucid wife Apame, was born in Cyrene, a Greek city in Libya. Ptolemy I had installed Magas, a son of his fourth wife Berenice I by a previous marriage, as governor of Cyrenaica (the northern coastal region of Libya). Magas eventually wrestled a measure of independence from Ptolemaic sovereignty but still had to acknowledge their suzerainty – and betrothed his daughter to the son and heir of Ptolemy II as a diplomatic and dynastic assurance. His half-Persian wife Apame was the daughter of Antiochus I and Stratonice. After his death (c. 252/1 BCE), Magas' widow married Berenice to the Macedonian prince Demetrius the Fair – who, however, offended the soldiers of the Cyrenean army and was assassinated in the bedroom of Apame. Whether this capture in flagrante delicto was a plot set up by Berenice in tandem with her mother or not remains a mystery. Cyrene briefly attempted to establish a republic (c. 250/49-249/8 BCE).

Queen & Regent in Alexandria

After this interlude in Cyrene, Berenice realigned with Egypt and renewed her marital pledges to Ptolemy III. After the natural death of Ptolemy II (c. Jan 246 BCE), his son succeeded to the throne, Berenice joined him in Alexandria, and they officially wed. He was 37; she had just turned 20. About half a year later the Seleucid king Antiochus II died with the succession unclear – his two rivaling queens Laodice and Berenice (sister of Ptolemy III) proclaiming their respective sons as heir to the throne. Deciding to intervene on his sister's behalf, Ptolemy III invaded Phoenicia and Syria, thus instigating what modern scholars have dubbed the Third Syrian War (c. Oct 246 - Mar 245 BCE). Soon after his sister's death in a palace plot (c. Nov 246), the Ptolemaic king entered Mesopotamia and besieged the Seleucid capital at Babylon (Jan 245 BCE).

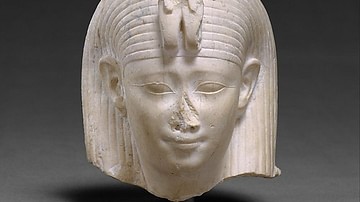

Meanwhile in Egypt, Berenice ruled as queen regent in command of the royal court in her husband's absence. A low flooding season signaled a poor upcoming harvest and thus the risk of food shortages soon after. Amid the unrest, Berenice gave birth to a daughter, Arsinoe III (c. Nov 246 BCE), rather than a much-desired crown prince. The queen alleviated the threat of famine by freely distributing imported grain. Some of the largest and most beautiful coins ever struck in antiquity, issued in her name and bearing her portrait, may be associated with this critical period. They show a veiled bust with highly individualized facial features, her hair fashioned in the so-called melon coiffure, pulled into a chignon and bound with a royal fillet. While individualized – and the basis for attributing sculptural portraits – such coin portraits should not be understood as faithfully realistic. The unnaturally globular eye, for instance, rather expresses the queen's divine authority.

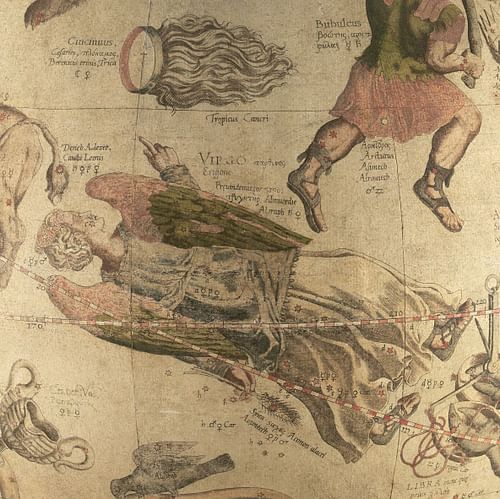

Berenice staged a public ceremony, leading a procession from Alexandria to Cape Zephyrium, a promontory on the coast near the mouth of the Canopic branch of the Nile. There she made a sacrifice at the temple of Arsinoe Zephyritis – that is, Berenice's deified predecessor Arsinoe II religiously identified with the goddess Aphrodite. She offered her “mother” a lock of her hair in hopes of the safe return of the king. At this point, events take a curious twist. According to tradition, priests at the temple discovered that the lock of hair had vanished the next day and suggested that the wind had blown it away. Some time later the mathematician and astronomer Conon claimed he had rediscovered the lock as a new constellation in the night sky – between Leo and Virgo, Boötes and Ursa Major. Whether the disappearance of the queen's lock was intended as part of the ceremony is impossible to determine.

Queenship in Ptolemaic Egypt

Literary sources rarely provide more than basic biographical information about women – even the powerful queens of the Hellenistic period. Among the four wives of Ptolemy I, only the influence of Berenice I was noted by ancient historiographers. The position of the Ptolemaic queen did change dramatically when Ptolemy II married his second wife and full sister Arsinoe II. They were deified as the Theoi Adelphoi (“Sibling Gods”); she received a lifetime cult under the epithet Philadelphos (“Brother-Loving”), which persisted for generations after her death. Their parents, Ptolemy I and Berenice I, were worshipped, too, as was Alexander the Great, who in a way became the dynastic founder.

Although Ptolemy III and Berenice II were cousins (as they shared the same grandmother, Berenice I), they proclaimed themselves siblings as children of Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II, perhaps from the time of their marriage – or at least from the time of the ceremony at Cape Zephyrium. Ptolemy III was actually the son of the first Arsinoe (the disgraced first wife of Ptolemy II). They, therefore, denounced three of their four parents in order to adhere to the ideology of sibling incest instituted by Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II. Royal incest became the norm, as only Ptolemy V (who had no sister) did not marry his closest female relative (though his wife Cleopatra I was still his cousin). To be sure, no genetic or congenital defects are known to have occurred among the members of the Ptolemaic dynasty (meaning no recessive mutations were carried down the generations).

Through the – occasionally fictitious – incestuous marriages the Ptolemies could present themselves as descendants of an unbroken line from both sides, thus legitimizing their rule twice over. Sibling marriage, moreover, was likened to the sacred marriage of Zeus and Hera, and of Isis and Osiris – thus deifying the royal couple. Temples were built with cult statues, priesthoods were created, festivals with processions were celebrated in honor of the living king and queen. Faience wine jugs (less expansive imitations of gilded silver vases) employed in the Ptolemaic cult, show Berenice with a cornucopia (horn of plenty) and a libation bowl bringing an offering on the crenelated altar of the Theoi Euergetoi (“Benefactor Gods”), the cult epithet given to her and her husband. (“Euergetis” is the feminine form of the title.) Brother-and-sister rule, furthermore, presented the king and queen as equals – jointly reigning as divine sovereigns in Egypt and beyond.

Representation in Hellenistic Art

On one of the relief scenes on the impressive gateway to the Chonsu Temple at Thebes (Karnak), Ptolemy III and Berenice II appear on the divine (rather than the mortal) side, receiving millions of years of rule from the titular falcon god Chonsu. The king wears a traditional pharaonic costume; the queen appears in a ceremonial robe that is wrapped over her shoulder and tied between her breasts. Their divinity is therefore displayed on one of the most ancient and most important religious sites of Egypt that may date back to the Old Kingdom. The scene is one of many examples in which the Ptolemies manifested their support for Egyptian traditions and customs, religion and cults, temples and priesthoods. The prominent position of the queen was, nevertheless, unprecedented.

Apart from statues and relief scenes, vases and coins, Berenice can also be recognized in floor mosaics (that are possibly reproductions of wall paintings). On one example (illustrated at the top of this article), discovered at Thmouis (modern Tell el-Timai) in the eastern Delta, Berenice II is portrayed with a corpulent face and wide-open bulging eyes; she wears ear pendants and a fine necklace, a tunic underneath a suit of armor, over which is a mantle fastened with a brooch over her right shoulder. The queen further carries a shield on her back; behind her proper left shoulder stands a yardarm from which flow the tasseled ends of a royal fillet. Most interestingly, she is crowned with the prow of a ship decorated with dolphins and marine serpents, herald's staffs, and horns of plenty. Berenice is thus displayed as the personification of Ptolemaic military and naval prowess.

The lock of hair, which the queen had purportedly offered to her “mother” Arsinoe-Aphrodite, actually survived the centuries. The ceremonious offering was immortalized by the Alexandrian poet Callimachus (Frag. 110) and later by the Roman poet Catullus (Poem 66). Among Renaissance artists, Berenice II was a beloved subject in visual arts as well as dramatic plays – and she remained so for centuries after. Indeed, her Lock of Hair (Coma Berenices) is one of the canonical constellations, and the only one named after a human being.

A version of this article was originally published at AncientWorldMagazine.com.