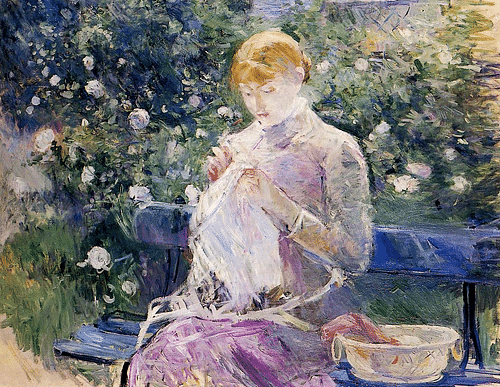

Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) was a French impressionist painter. She was admired by fellow artists, had multiple works exhibited by the Paris Salon, and had her paintings shown in seven of the eight independent impressionist exhibitions in Paris. Her distinctive style of long, quick brushstrokes was used to capture with great effect the spontaneity of such scenes as flowering gardens and domestic life.

Early Life

Berthe Marie Pauline Morisot was born in Bourges on 14 January 1841, the daughter of a well-to-do local official, Tiburce Morisot. Her mother was Cornélie Fournier. Her interest in art began as a teenager when, after the family moved to Paris in 1855, she started studying and copying masterpieces on display in the Louvre. Here she would have met many other artists doing the same studies. Art was in her genes as one of Morisot's ancestors was the renowned Rococo painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732-1806).

By 1860, Morisot was taking some art lessons under Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1797-1875). Unfortunately, the career path to becoming an artist, already a difficult one, was made even more tortuous for Morisot because of the prejudice against women in that field. It would have been a logical next step to study at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, but unfortunately, they did not accept women.

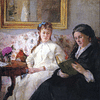

At least Berthe had the support of her parents. Indeed, her elder sister Edma (1839-1921) also became a painter; she memorably captured her more famous sibling working at her easel in an 1865 portrait. Another artist tutor was Joseph Guichard (1806-1880) and he wrote the following note to the two sisters' father:

Considering the character of your daughters, my teaching will not endow them with minor drawing-room accomplishments; they will become painters. Do you realize what this means? In the world of the grande bourgeoisie in which you move, this will be revolutionary, I would even say catastrophic. Are you sure that you will not come to curse the day when art, having gained admission to your home, now so respectable and peaceful, will become the sole arbiter of the fate of your two children?

(Howard, 150).

Berthe Morisot: A Gallery of 30 Paintings

Despite these warnings, Morisot pursued her talent with passion, and in 1864, she submitted her first work for exhibition at the Paris Salon, the place to be for artists wishing to secure a name, reputation, and clients. The submission was accepted, and this success led to her father constructing a purpose-built studio in the family gardens in 1865. In 1866, Morisot was again accepted by the Salon; her career was made, and more acceptances by the Salon would follow.

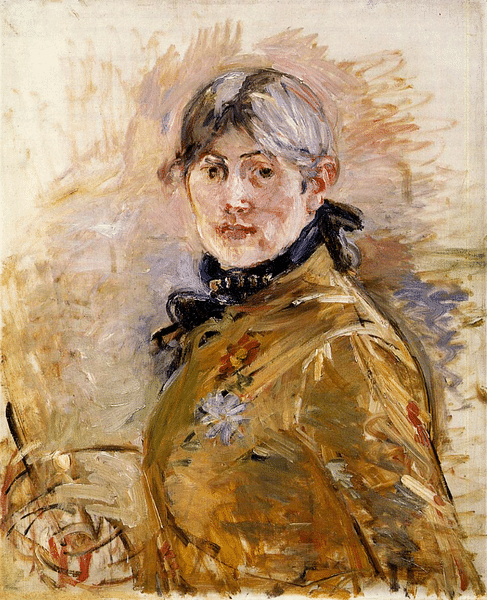

The art historian V. Bouruet Aubertot gives the following description of Morisot:

Tall and slender, extremely distinguished in her bearing and intelligence, Berthe Morisot was a dark Baudelairean beauty, who was enigmatic, very courteous, and fiercely independent. (332)

Relationship with the Manets

Morisot appears in many paintings by Edouard Manet (1832-1883), the French modernist painter she first met in the Louvre in 1868. She appears in such iconic works as The Balcony (figure on the left), painted in 1868-9. Morisot was not entirely captivated by the finished work, noting to her sister Edma, "I am more strange than ugly," and the whole scene seemed to her like "a wild or even unripe fruit" (Roe, 55).

Alone, Morisot was a favourite sitter for dramatic portraits by Manet, featuring in eleven works. In The Repose (1869-70), she reclines languidly on a plum-coloured sofa. In the more traditional Berthe Morisot with a Bouquet of Violets (1872), her face is dramatically framed by the black of her dress, scarf, and hat. Morisot learnt from Manet, and perhaps vice-versa, but Berthe did not accept a subsidiary role in their professional relationship. When Manet added some touches to Morisot's portrait of her sister, a work which had been accepted by the 1870 Salon, she was furious.

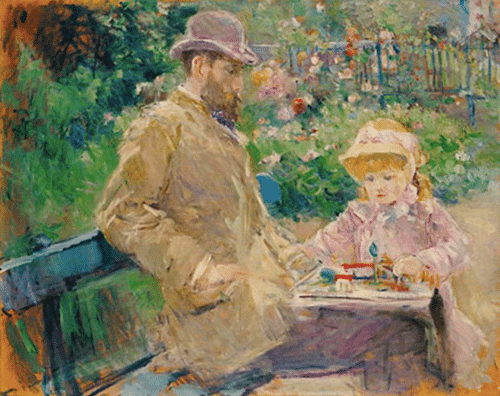

The precise relationship between Manet and Morisot is not known, they may have been more than friends, but that relationship must surely have changed when she married Manet's brother Eugène (1833-92), also a painter, on 22 December 1874. They had a daughter together, Julie, born in 1878; she is captured in Morisot's 1884 painting Julie with a Doll and many other works.

Technique & Style

Morisot used the typical approach of many of the impressionists to paint plein air or 'in the open air' rather than the traditional method of sketching a subject and then actually painting it in the studio. The idea was this method made it easier to capture illusory impressions of light and colour. There were some practical drawbacks, though, as Morisot noted in a letter to her sister where she describes her plein air painting on the Isle of Wight in 1875:

Everything sways, there is an infernal lapping of water; one has the sun and the wind to cope with, the boats change position every minute…The moment I set up my easel more than fifty boys and girls are swarming about me, shouting and gesticulating. All this ended in a pitched battle, and the owner of the field came to tell me rudely that I should have asked permission to work there…

(Howard, 29)

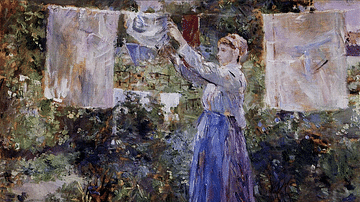

In addition, Morisot rarely made a preliminary sketch on the canvas but painted directly, again to maintain a spontaneous affinity with the brush and the temporary scene of light and colour she was looking at. The result is Morisot's distinctive long and fast brushstrokes. The search for spontaneity was not without its drawbacks, too, and many critics considered Morisot's work unfinished, a criticism that was directed at many of the other impressionists.

Regarding Morisot's matching of this style with her choice of subject, the art historian M. Howard gives the following summary:

Her paintings were generally praised, both within and without the Impressionist circle, for their lightness of touch and her skilled rendering of outdoor effects. Beneath the atmosphere of ease and relaxation apparent in her work, there is an underlying quality of melancholy and introspection that characterizes her work. Her paintings are light-filled and brilliantly informal, both in subject and technique, characterized by a sense of sketchlike improvization informed by close observation. (151)

It is for all of the above reasons that, in 1874, the art critic Paul Mantz described Morisot as the "one real impressionist" (ibid). This opinion was echoed in 1881 by another critic, Gustave Geffroy: "No one represents Impressionism with more refined talent or with more authority than Morisot" (ibid).

Independent Exhibitions

In the 1860s, a group of young avant-garde artists hung about together in the cafés of Paris. They passionately discussed what should be the new direction of art, especially the Café Guerbois and others in the Batignolles area of Paris. This group included such future household names as Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), Edgar Degas (1834-1917), Claude Monet (1840-1926), and Edouard Manet. They were also joined by literary men like Émile Zola (1840-1902). Morisot was a member of this group, which became known as 'the Batignolles', and a popular one with her beauty, charm, and talent. Indeed, she turned down two marriage proposals: from artist Puvis de Chavannes and statesman Jules Ferry. However, as a respectable woman she could not be seen in some of the cafés the male artists gathered in, and she often had to content herself with their company in a private setting.

The 'Batignolles' and other artists who could not regularly win the approval of the ultra-conservative Salon jury, decided in April 1874 to create their own exhibition space, the First Exhibition of Independent Artists, later more commonly known as the First Impressionist Exhibition. Morisot, Monet, Degas, Renoir, Manet, and Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) were all represented in the exhibition. Morisot had nine paintings, watercolours, and drawings on display. The show was a success in terms of visitors – over 4,000 – but not in terms of sales or the response from the mainstream critics who had a field day. Still, it was the first move that challenged the dominance of the Salon, and it would not be the last.

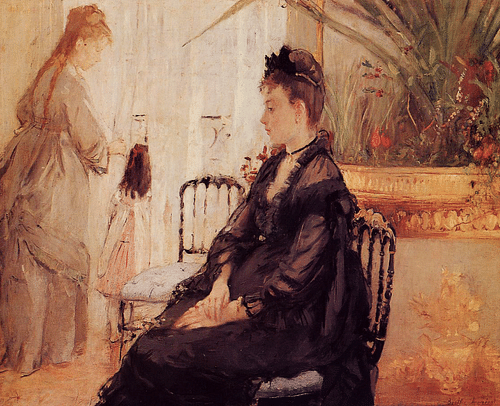

In March 1875, the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel organised a public sale in the Hôtel Drouot of Paris. On show were paintings by Monet, Renoir, and others, and 12 by Morisot. The critics once more did what they always did: criticised, but there were some favourable reviews in the more radical press. At the auction itself, Morisot came in for particular abuse. When Morisot's very first work was shown, a man in the audience shouted gourgandine ("whore"). Camille Pissarro got up and punched the man, and the police were called in before the auction could proceed. Still, of all the works on offer, Morisot's Interior got the highest price tag for a sale: 480 francs (a Renoir was picked up for a mere 180 francs).

By the time of the 8th Impressionist Exhibition in 1886, Morisot and Eugène Manet were in a position to finance the whole thing. When Edouard Manet died in 1883, the couple arranged for a retrospective exhibition of the late artist's work at the École des Beaux-Arts. Morisot, like some of the other impressionists, now began to cause a stir in the Americas; her works featured in an 1886 exhibition organised by the American Art Association of New York. This was the first time Americans had seen such a comprehensive exhibition of impressionism, and they were much more enthusiastic than the reactionary critics back in France.

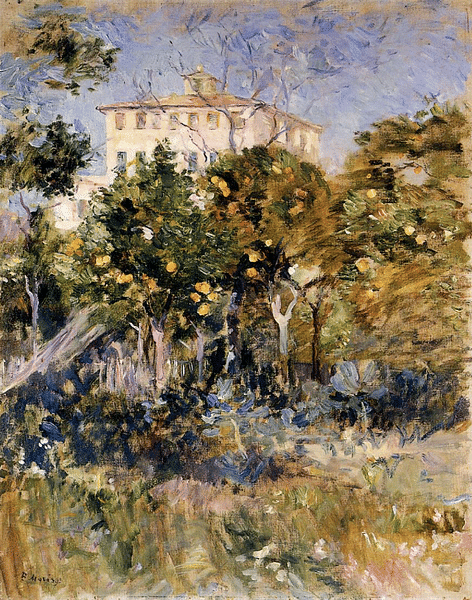

Morisot's home in Bougival, just outside Paris, continued to regularly host gatherings of a wide range of Parisian artists and intellectuals. Here, Morisot frequently painted scenes of the garden in flower and the nearby Bois de Boulogne. In 1891, the family moved to a new house in Mesnil and this, too, was captured in paint several times. Restricted by the social conventions of the period where a woman painting in a too-public a place would have caused problems, Morisot's body of work focusses on domestic scenes, her garden, and her daughter.

Death & Legacy

Eugène Manet died in 1892, and Berthe's health declined rapidly thereafter. Consequently, she went to live with her daughter but continued to paint when she could. Berthe Morisot died suddenly of pneumonia in Paris on 2 March 1895. On her death certificate, and significant of the prejudices she had to battle with throughout her career, under 'profession', it is written "none". Others were in no doubt, though. The painter's entire body of work was presented in an exhibition in a gallery in Paris, a show organised by such prominent figures as Renoir, Degas, and Monet, all of whom had regarded Morisot as their equal in the ultimately victorious battle to change the world of art forever.

Morisot was one of the few successful female painters, and this success helped lift at least some of the obstacles against female artists. In 1897, the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris began to accept women. Morisot was also instrumental in introducing a more feminine view of the world than male painters had previously done. Her painting of her husband playing with their daughter in the garden was not a typical subject for a male artist who would have chosen the mother and child as his subject. In another example, knowing quite how uncomfortable fashionable women's clothes were to wear, Morisot painted her women wearing them in reality with odd buttons and ribbons astray, and so not the often posed, model-like way many male artists did. Although Morisot's reputation faded over the next half-century, she rose again to prominence thanks to feminist art historians who replaced her in her rightful place amongst the pantheon of great impressionist painters.