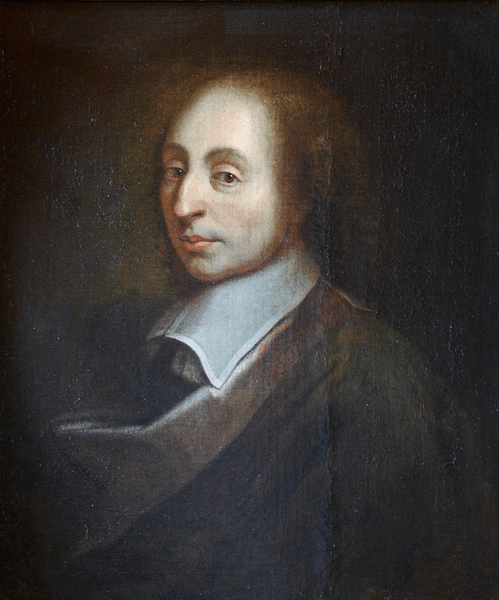

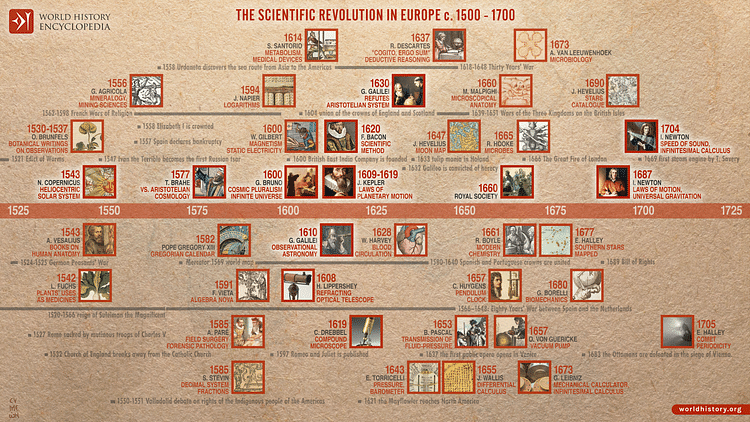

Blaise Pascal (1623-1662) was a French scientist, mathematician, and philosopher whose work influenced both the Scientific Revolution and later European thought. Pascal is known for his practical achievements in science, such as a calculating machine, demonstration of the variations possible in air pressure depending on altitude, and a theory of probability.

Pascal is also known for his more theoretical religious and philosophical writings, such as the posthumously published Pensées, which contains his famous win-win advice for wavering believers in God, a choice known as Pascal's wager.

Early Life & Mathematics

Blaise Pascal was born in Clermont-Ferrand in central France on 19 January 1623. His father, Étienne Pascal (1588-1651), was a magistrate in the local tax court and a very useful mathematician. The family moved to Paris in 1631. Blaise was educated by his father and showed a great talent for mathematics as a child. Aged 12, he worked out that the sum of a triangle's internal angles always equals two right angles. He published a theoretical paper on conic sections while still only aged 16. The young Pascal was proudly shown off in the salons of Paris as a child genius.

By 19 years of age, Pascal had already invented a calculating machine, intended to help his father with his tax calculations. The machine, made up of a brass box with six wheels and paper markers, weighed a hefty 2.5 kilograms, but it is relatively small (about 28 cm or 11 in. in length). The user took a stylus to turn the various wheels to the desired configuration, and the machine could do both additions and subtractions. Pascal filed a patent for the device, but, unfortunately, without the technology to mass-produce it in sufficient numbers, the idea did not take off. A replica of Pascal's machine is today held in the Conservatoire National de Art et Metiers in Paris. Pascal's lack of a university education had proved to be no handicap at all.

Another achievement was Pascal's work in 1654 with fellow French mathematician Pierre de Fermat (1601-1665) – largely conducted via letters – where they discussed two problems. The first problem was how to determine the frequency of throwing double sixes using two dice and a certain number of throws. The second problem they discussed was how to share out the original betting stakes if a dice game had to be interrupted before its planned conclusion. Pascal and Fermat's work resulted in what would become the basis for the modern theory of probability. The historian E. Cameron explains this shift as follows:

It was only in the 1650s and 1660s that a new conception of probability suddenly became a major theme, with Pascal and Leibniz among its outstanding exponents. the word 'probable' itself was in the process of changing its meaning from 'supported by authorities' to 'likely in view of all the evidence'.

(203)

Pascal has several mathematical phenomena named after him, even if he was not always the first to discover them. "Pascal's theorem" describes the properties of a hexagon inscribed in a conic section (Burns, 235), "Pascal's triangle" deals with the arrangement of integers, and "Pascal's principle" is used in hydraulics as it reveals that pressure upon one area of a liquid (providing it is confined) will result in its equal expansion in all directions.

Pascal the Scientist

Pascal was a great experimenter, and he was in full agreement with Francis Bacon (1561-1626), often regarded as the founder of the modern scientific method, in that he believed in the necessity for practical experimentation in order to expand our knowledge of the world. Pascal admired the ancients, too, for their practical attitude to science, but he was also keen to point out that, despite the Renaissance vogue for revering antiquity, they did not discover everything (he was thinking particularly about vacuums) and that his own generation should certainly strive to make their own brand new enquiries:

Those whom we call ancient were really new in all things, and properly constituted the infancy of mankind; and as we have joined to their knowledge the experience of the centuries which have followed them, it is in ourselves that we should find this antiquity that we revere in others. (Gotttlieb, x)

Pascal was especially interested in vacuums, a phenomenon that some thinkers and natural scientists still believed did not and could not exist (how can "nothing" ever exist? they asked). He also conducted experiments with a barometer – another new field of science – in order to demonstrate that air pressure changes with altitude. In 1648, Pascal and his brother-in-law Florin Périer conducted their experiments by setting up devices composed of tubes filled with mercury at a variety of positions on the side of a mountain, Puy-de-Dôme, in the Massif Central of France. The scientists noted that the level of the mercury in the glass tube fell the higher up the mountain the readings were taken. Pascal hoped that his barometer might be used to measure height, but this idea was scuppered when it was realised that atmospheric pressure is not constant.

Pascal's experiments with fine tubes and liquids did lead him to create the first simple syringe. The barometer experiments also led to steps forward in the field of hydraulics, a subject Pascal wrote about in A Treatise on the Equilibrium of Liquids (published only in 1663). Although Pascal wrote on the theoretical possibility of vacuums in his 1647 work New Experiments on the Void, the puzzle of establishing a controllable vacuum was eventually solved by Robert Boyle (1627-1691) using a glass dome and an air pump.

The historian S. Blackwell notes another Pascal achievement: "Pascal had a deep concern for the poor, and founded the first ever public bus service, whose profits he gave to charity" (351).

Retreat to Port-Royal

Towards the end of 1654, Pascal experienced some kind of burst of personal enlightenment after he miraculously survived a travel accident. Pascal's carriage crashed and almost fell off the side of a bridge, he was saved only because the harnesses holding the horses snapped, otherwise they would have pulled Pascal to certain death. After this lucky escape, which took Pascal two weeks to recover from, he became focussed on religious studies, which led to him re-converting to Catholicism. In early 1655, he decided to withdraw from his more secular and practical scientific studies and concentrate on philosophy and theology. Pascal moved to a life of retreat in the Abbey of Port-Royal-des-Champs, not far south of Paris. The abbey was run by the Jansenists, indeed, it was the very heart of this puritanical movement within Catholicism that strictly followed the teachings of Augustine of Hippo (354-430).

Pascal's sister was already a nun at the Port-Royal abbey, and here, he worked on De l'esprit géométrique, written around 1658, which presents Pascal's ideas on his preferred methodology for both science and philosophy. He also wrote what became his most famous work, Pensées (Thoughts), an unfinished collection of notes, which was, like De l'esprit géométrique, only published after Pascal's death (and not completely until 1952). Pensées is a defence of Pascal's religious views. He formulates the idea that "God is not known through study of the laws of nature but rather is manifest in the very miracles that violate those laws" (Burns, 120). Pascal thought that he had himself experienced one such break of the laws of nature in 1656 when his niece miraculously recovered from a seemingly fatal illness. Above all, for Pascal, it is through the individual's imagination or intuition rather than through reason that an individual can come to know God.

Another work he compiled during his retreat was Lettres provinciales (aka Les Provinciales, 1656-7), which attacked the Jesuits, the primary opponent of the Jansenists. Despite Provinciales' popularity, the Jansenists fought a losing battle, and Port-Royal was closed down in 1661. Both Lettres provinciales and Pensées have been praised for Pascal's taut and eminently readable writing style, quite different from what was then the norm in religious-themed texts.

Pascal's Wager

Although Pascal was in some ways a sceptical philosopher, he relied much more on faith than reason for his personal religious beliefs. He did, however, propose an interesting solution for those who can not quite decide if God and an afterlife exist. It was not an entirely new idea, but Pascal formulated in more formal terms a "best bet" scenario regarding faith in God. If one is not sure, then it is a better bet to believe in God because if one is mistaken and God does not actually exist, one loses nothing. If one does not believe in God and there is an afterlife, then one risks eternal damnation. In Pascal's own words:

If you gain, you gain all. If you lose, you lose nothing. Wager then, without hesitation, that He exists.

(Law, 114)

The options then are essentially win big or lose big. Believing in God is, as a consequence, the rational choice. There are, according to Pascal, additional benefits to faith in God besides securing one's soul in the afterlife since he thought such a believer was less likely to indulge in "poisonous pleasures" (Blackburn, 352) and behave better to other people.

Pascal did recognise that believing one thing instead of another sincerely is not merely a matter of flicking a switch in one's brain, as some critics have pointed out. His advice was to start by doing what other believers do, like regularly going to church services and reading the Bible. He suggests one should spend as much time as possible with other believers since he thought that faith was, at least to some degree, infectious, and so this environment would gradually convince an unbeliever into truly believing.

Some critics, notably W. K. Clifford (1845-1879), have pointed out that Pascal seems to be putting truth in a subordinate position to self-interest. Under Pascal's wager, the believer is only believing because it seems the best thing to do. Further, God would know this, and so one risked being damned forever anyway.

Another criticism is that Pascal's bet has only two outcomes, and it is presented as a 50:50 chance, when in reality, there may be more possible outcomes, and the bet is not even. For example, there may be a God, but he/she may be nothing like the Christian one, and so believing in that version of the supreme deity may not be sufficient to gain a blissful afterlife. Others might argue that as there is no evidence at all of a God in the physical world, the bet is not a clear 50:50 he/she exists or not, rather, the chances of God existing are much more remote. In this case, and if we keep the wager analogy, then betting on God could be a 1,000 to 1 long shot. That fact would seriously compromise Pascal's argument that one has nothing to lose spending time in church and reading the Bible. At a 1,000:1, a person might re-evaluate that potentially lost time as too great a price to pay for too small a probability of winning the bet.

Death & Legacy

Pascal was troubled by a serious stomach complaint in his later years. The resulting insomnia from this affliction led him to return to pondering problems of mathematics and geometry. One problem was how to determine the area of a specific segment of the cycloid ("the curve formed by a point on the circumference of a circle as it rolls along a straight line", Burns, 78). Pascal, his mind as sharp as ever, found the solution and then published the problem, challenging anyone to find the answer. Some of Europe's most eminent thinkers took on the challenge, and some replied with the correct answer, notably the Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens (1629-1695) and the English architect Christopher Wren (1632-1723).

Pascal died in Paris on 19 August 1662. He was just 39 years of age. Pensées has since become "an acknowledged classic of devotional literature" (Blackburn, 351), and so Pascal is the only major scientist of the Scientific Revolution to "attain greatness in both science and literature" (Burns, 171). Pascal's scientific experiments and work in mathematics, as we have seen, created laws and principles which have helped others to build upon his work to make further discoveries. Pascal's thoughts on religious belief were influential, too, especially on Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778). More recently, for his contribution to early computing machines, Pascal has been honoured by having a programming language named after him.