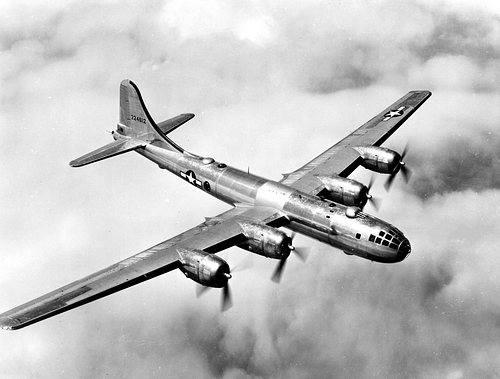

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress was a four-engined, long-range bomber of the United States Air Force. The largest of all Second World War (1939-45) bombers, B-29s were used to strike Japanese targets from the summer of 1944. In August 1945, the B-29s 'Enola Gay' and 'Bockscar' each dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively, thereby ending the war.

Development

In the 1930s, the United States Army Air Corps (USAAC) required a long-range strategic bomber that could attack enemy targets thousands of miles from the aircraft's home base. One of the problems to make such an aircraft a reality was to find engines which were powerful enough for the task. The project to design and build a long-range, high-altitude precision bomber, or VLR (Very Long Range) as such aircraft became known, was greatly accelerated following the invasion of Poland in 1939 by Nazi Germany and the outbreak of WWII. In January 1940, five aircraft companies were tasked with designing a VLR bomber. Four companies came back with a design proposal: Consolidated, Douglas, Lockhead, and Boeing. After two of the companies later withdrew, only Consolidated and Boeing won construction contracts in September 1940. Ultimately, each company built three prototypes. Boeing's construction plans were more advanced since it had already been working on modifications of its existing Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress design. Boeing received an order of 1,500 VLRs and promised these aircraft would be ready within three years.

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in Hawaii, home of the US Pacific naval fleet, on 7 December 1941, the need for VLRs in the vast theatre of the Pacific Ocean suddenly became a necessity. The first Boing VLR prototype, called XB-29, flew on 21 September 1942. The very large wings of the craft were designed to help it land at lower speeds, and tricycle landing gears helped bear the tremendous weight. 14 test aircraft began to fly from June 1943. The planes were built at four principal plants: Renton, Wichita, Marietta, and Omaha. Boeing, Bell, and Martin were just three of the main companies involved, but there were thousands of others providing components and partial assembly. The B-29 project "was the largest aircraft manufacturing project undertaken in the USA during World War II" (Mondey, 29). It was also the most expensive. From the autumn of 1943, the first B-29 bombers were delivered to US air bases.

Design & Specifications

The B-29 Superfortress was the largest aircraft built during WWII and had a crew of up to 11, but this number could be reduced if, for example, gunners were not deemed necessary for a specific mission. The aircraft had four Wright Cyclone radial engines, each with twin General Electric turbochargers and capable of giving a combined 23,200 hp. The massive engines gave the aircraft more power than any other aircraft of the time. This power was certainly needed since the weight of a fully-laden B-29 was around 60 tons. A B-29 had a wingspan of over 141 feet (43 m) and a length of 99 feet (30.18 m). Each of the B-29's giant propellers measured 16 feet 7 inches across (5.05 m).

Innovations included being the first aircraft to have fully-pressurised compartments for the crew (the pilot's cabin, accommodation unit, access crawl tunnel between those two parts, and the rear gun turret). Another new feature was a centralised control system for the aircraft's guns. The B-29 had comfortable seats, rest bunks, and even a galley, such were the length of flights the crew were expected to serve on.

The B-29 was specifically designed to operate in the Pacific arena of WWII, where vast distances separated fields of conflict and target areas. The aircraft could fly at an altitude of more than 33,000 feet (10,058 m) and maintain, according to the National Museum of the United States Air Force, a maximum speed of 357 mph (574 kmh) when free of its bomb load, which could weigh up to 20,000 lbs or 9,072 kg (for example in the form of 500-lb bombs divided into two bays). The range of the aircraft was up to 5,000 miles (8,046 km) when carrying a more modest bomb load of 2,000 lbs (907 kg), although range could also be greatly affected by favourable or unfavourable winds at high altitudes.

The B-29 had a formidable array of defensive weapons. There were two machine gun turrets in the upper fuselage and two in the lower fuselage, each with twin 0.50-inch (12.7-mm) guns (although some versions had four guns in the forward upper turret). The two upper turrets each had a blister window set behind them to aid sighting of the guns. There was another gun position in the tail, again with 0.50-inch twin machine guns but also sometimes with the addition of a 20-mm cannon. The guns each had 1,000 rounds of ammunition. The special B-29A model also had a nose gun turret with four machine guns. The remote-controlled machine guns could be operated by a single crew member, the Fire Gun Controller, who sat in a raised chair that was nicknamed the 'barber's chair'.

Many flight crews personalised their B-29 by painting a large and colourful name and picture just behind the pilot's side windows. Most popular were names of girls with a pin-up like picture. Examples of such names include 'Supine Sue', 'Horezontal Dream', 'Dauntless Dotty', 'Battlin Betty III', and 'Over Exposed'.

Operations

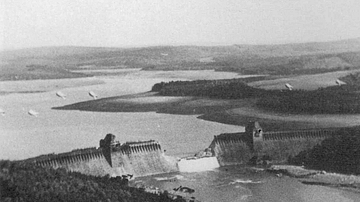

The first operational B-29 Superfortresses were designated to the newly formed 20th Air Force. The first planes were sent to the Pacific theatre of the war in April 1944, specifically bases in China from where the bombers could strike mainland Japan. Chinese labourers were enrolled to create the long airfields necessary for such giant aircraft. In the end, four runways were constructed in the Chengtu region of China's Szechwan province. Supplies had to be flown in from India, which meant crossing the high Himalayas. Through the summer of 1944, China-based B-29s made bombing raids on such targets as the Imperial Iron and Steel Works at Yawata on Kyushu. However, the logistical difficulties of receiving supplies from India and the great distances involved meant that these raids did not achieve their ultimate objective of seriously weakening the Japanese war machine, as here explained in The Oxford Companion to World War II:

The China-based raids…proved of limited value. Of nearly 50 B29 attacks flown from China in 1944 and early 1945, only nine actually hit Japan, and these and others against targets in Manchukuo, Korea, China, Formosa, and South East Asia did little strategic damage. They provided valuable experience for the bomber crews, but otherwise hardly justified their cost and effort.

(840)

What were needed were bases closer to Japan itself. As the Pacific War progressed in the United States' favour, certain well-placed islands became available for use as air bases. The Marianas group, which included such islands as Saipan, Tinian, and Guam, hosted B-29 squadrons following their capture by US forces in August 1944. Saipan was the closest island to Japan, located around 1,200 miles (1,930 km) from Tokyo, and became the main US strategic bomber base from October 1944. The first B-29 raid from the Marianas took place on 24 November 1944, when 80 Superfortresses bombed an aircraft factory in Tokyo.

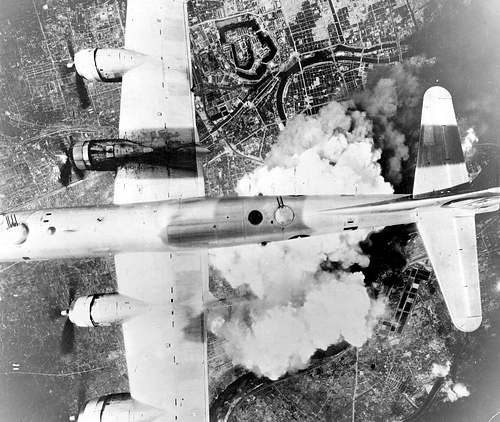

In contrast to what they were initially designed for – high-altitude precision bombing – most B-29s were deployed from February 1945 to drop tons of incendiary bombs on Japanese cities from a low altitude. High-altitude bombing had proved problematic due to high winds from the jet stream affecting accuracy, and daylight was required for the bombsighters, which exposed the aircraft to Japanese fighter attacks. Seeing the consequences of such incendiary bombing raids on German cities as Operation Gomorrah against Hamburg in August 1943 during the Allied bombing of Germany, the US Air Force decided to apply the same tactics on Japan. The incendiary bombing caused devastation amongst the highly combustible wooden architecture that predominated in Japanese cities. These bombing raids were carried out at night at a relatively low altitude of 6,000 feet (1,830 m), often dropping napalm-filled incendiary devices that spread fire as they exploded. The lower altitude meant the B-29s could carry a greater bomb load, which was further increased when it was decided not to take the gun crews.

A major B-29 raid was carried out on Tokyo on the night of 9 March 1945. 334 bombers set out from Guam, Saipan, and Tinian and destroyed over one million homes in Japan's capital. Over 87,000 people were killed, and nearly 41,000 were injured in the attack and the consequent firestorm (Neillands, 378). Other cities given the same treatment of indiscriminate incendiary bombing included Nagoya, Kobe, Kawasaki, Osaka, and Yokohama. These cities were often hit by 500 B-29s in a single attack. 60 smaller cities in Japan were also bombed, the B-29s mixing precision bombing, which aimed at specific industrial or military targets, with indiscriminate incendiary bombing.

In total, during WWII, B-29s "dropped some 160,000 tons of bombs on Japanese targets" (Mondey, 32). The US bombing raids caused at least 800,000 civilian casualties (which includes 300,000 deaths) and made 8.5 million people homeless. Still, the military-dominated Japanese government fought on, hoping that Japan could inflict such high casualties on the enemy in what seemed an inevitable US invasion that a surrender could be negotiated on more favourable terms.

Other roles of B-29s besides bombing cities included the support of amphibious assaults, such as at Okinawa in April 1945. As more Pacific islands were captured, like Iwo Jima (March 1945), long-range fighters such as P-51 Mustangs could now escort the heavy bombers and reduce B-29 losses to well below the 5% figure commanders considered acceptable. During the war, B-29s were operated not only by the United States Air Force but also by Britain's Royal Air Force and the Royal Australian Air Force. Of all these aircraft, two bombers, in particular, would become famous for their role in delivering a new and devastating weapon and doing what all the other bombing raids had failed to achieve: ending WWII.

The Atomic Bombs

The Allies had gained victory in Europe after the surrender of Nazi Germany in May 1945, but Japan kept on fighting. The United States, in particular, was keen to end the Pacific campaign as quickly as possible and minimise US casualties as Japanese forces retreated island by island, often fighting to the death and causing heavy casualties on the victors. In addition to these 'official' arguments, a demonstration of the United States' terrible new atomic weapon might prove very useful indeed in the inevitable shakeup of political power in Europe, East Asia, and elsewhere after the war was concluded. The dropping of the atom bomb would, above all, demonstrate to the USSR the military might of the United States.

Two B-29 bombers of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron were selected to carry one atomic bomb each to strike two major Japanese cities such devastating blows that the Japanese military government would be obliged to surrender. The 'Enola Gay' carried an atom bomb to Hiroshima while 'Bockscar' took one to Nagasaki. Both aircraft took off from Tinian, and both bombs would be dropped by parachute to explode at a height of around 1,625 feet (500 m) from the ground.

The 'Enola Gay', named after group commander and pilot Colonel Paul Tibbets' mother, carried a uranium 235 atomic bomb nicknamed 'Little boy' in honour of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945). The bomb measured 9 feet 9 inches (3 metres) in length, weighed almost 8,000 lbs (3,600 kg), and had an explosive power equivalent to 12.5 kilotons of TNT. Hiroshima was hit on 6 August 1945. Geoffrey Leonard Cheshire, an official British observer in another plane that flew with the 'Enola Gay', remembered:

The flash just lit the cockpit, the moment I first saw it, it was like a ball of fire, but the fire rapidly died down and became a churning, boiling, bubbling cloud, getting larger and larger and rocketing upwards and I would think that within 2 or 3 minutes it was at 60,000 ft.

(IWM)

Estimates vary, but perhaps as many as 140,000 people were killed in the attack as over 5 square miles (13 square kilometres) of the city were reduced to ashes.

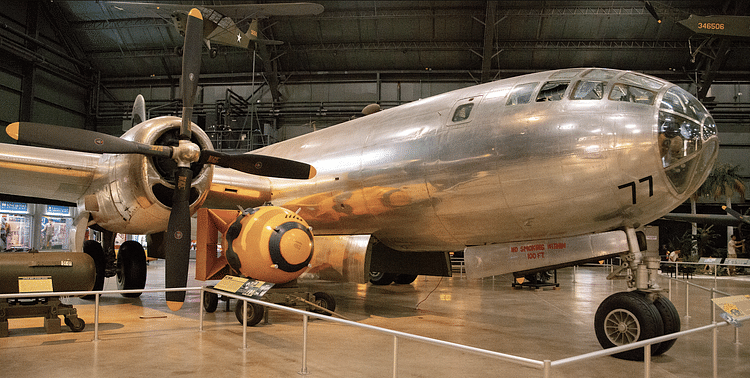

'Bockscar', named after its pilot commander Captain Frederick Bock, carried a much more powerful plutonium 239 atomic bomb nicknamed 'Fat Boy' in honour of the portly British prime minister, Winston Churchill (1874-1965). This bomb measured 11 feet 4 inches (3.5 metres) in length, weighed over 9,000 lbs (4,000 kg), and had an explosive power equivalent to 22 kilotons of TNT. Nagasaki was hit on 9 August. The bomb killed around 74,000 people and injured another 75,000 as around 2.6 square miles (6.7 square kilometres) of the city were reduced to ashes. In both atomic bomb attacks, thousands of survivors suffered the negative effects of radiation exposure later in life. The Japanese emperor, Hirohito (1901-1989), declared Japan's willingness to surrender on 15 August 1945.

End of Service

B-29 bombers continued to see service, notably in the Korean War (1950-53), and some were used to transport fuel for other aircraft. In all, 3,930 B-29s (Dear, 114) were built, but by the end of 1960, the last B-29 had flown on active service. The bomber had certainly impressed friend and foe alike. In the summer of 1944, three B-29s were obliged to make emergency landings in Russia. The capture allowed Soviet designers to reverse engineer an almost exact copy of the B-29, the Tupolev TU-4.

The B-29 aircraft was superseded by even larger bombers such as the Boeing B-50 Superfortress, the Convair B-36 Peacemaker, and the Boeing B-47 Stratojet. Two B-29s, 'Fifi' and 'Doc', remain airworthy today, and they occasionally perform at airshows. 'Bockscar' can today be seen at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, Dayton, Ohio, while the 'Enola Gay' is on display at the National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia.