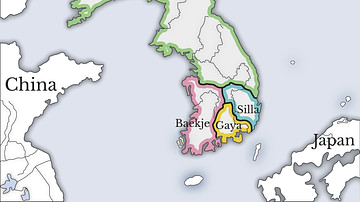

The Bone Rank System (Golpum or Kolpum) of ancient Korea was used in the Silla kingdom (57 BCE – 935 CE) in order to signal a person's political rank and social status. Membership of a particular rank within the system was extremely important, permitting a person to apply for certain jobs and deciding how they lived their everyday lives. The rigidity of the system, based as it was on lineage, allowed for very little movement between the classes resulting in a stagnation of talent, which eventually cost the Silla dear.

The Ranking System

The Bone Rank System, so called because it was based on a person's hereditary bloodline, was introduced as part of a new law code in 520 CE by king Beopheung (r. 514-540 CE) . This caste system had three main classes: the highest was 'sacred bone' (seonggol), then 'true bone' (jingol), and finally 'head rank' (tupum). The Silla kings, descended from the Pak royal line or their successors the Kims, were all of the sacred bone class. From the mid-7th century CE the sacred bone class was abolished and, thereafter, royalty held the true bone rank along with lesser royals, ministers of high office, and high-level aristocrats.

The head rank class was the largest and itself divided into six subclasses. These were numbered with ordinary people belonging to class one, two, and three. The aristocracy belonged to levels four, five, and six. These top three levels were linked to a person's family ties and/or land they owned, and certain clans dominated the higher positions.

Privileges & Restrictions

Membership of the head rank class was necessary for a person to be considered for civil and military roles in the state apparatus, with the most senior positions reserved for those in the higher numbered subclasses. One's bone rank decided the type of people one could interact with socially, who one could marry, and how much tax had to be paid to the state. Further, membership of a specific level was necessary for a person to enjoy a certain type of housing, not only the size but also decoration as, for example, ceramic roof tiles (instead of thatch) were a very practical and visible badge of rank in Korean society. Bone rank decided which transport people might use, the type of saddle they could sit on, the number of servants they were permitted to have, and even which utensils they could use. Clothes were another visible indicator of social status. Men who were members of the true bone class were not permitted to wear clothes which had embroidery, brocade, or fur, while only women of the sacred bone rank could wear hairpins inlaid with jade or gemstones.

Social Immobility

Although a particularly appreciated service to the monarch or a senior government official might bring a reward of land and titles, there was, otherwise, not much chance of climbing the social ladder. As the historian K.Pratt notes, "Social mobility was rare, and for most people their occupational and social status was inherited" (79). That is to say, one's birth was by far the most important factor in determining the level one would reach in society as an adult. Even the son of a merchant might expand his father's business considerably, but this new wealth would not have entitled him to access the higher levels of the bone rank system.

The rigidity of the system allowed those who had power to keep it unchallenged, but one of the unfortunate consequences of it was that talent often went unrewarded and the state lost the opportunity to use gifted individuals for the good of all. Indeed, this social stagnation has been cited by many scholars as one of the factors leading to the ultimate downfall of the Silla regime.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.