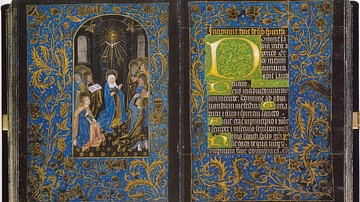

The Book of Kells (c. 800) is an illuminated manuscript of the four gospels of the Christian New Testament, currently housed at Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland. The work is the most famous of the medieval illuminated manuscripts for the intricacy, detail, and majesty of the illustrations. It is thought the book was created as a showpiece for the altar, not for daily use, because more attention was obviously given to the artwork than the text.

The beauty of the lettering, portraits of the evangelists, and other images, often framed by intricate Celtic knotwork motifs, has been praised by writers through the centuries. Scholar Thomas Cahill notes that, “as late as the twelfth century, Geraldus Cambrensis was forced to conclude that the Book of Kells was “the work of an angel, not of a man” owing to its majestic illustrations and that, in the present day, the letters illustrating the Chi-Rho (the monogram of Christ) are regarded as “more [living] presences than letters” on the page for their beauty (165). Unlike other illuminated manuscripts, where text was written and illustration and illumination added afterwards, the creators of the Book of Kells focused on the impression the work would have visually and so the artwork was the focus of the piece.

Origin & Purpose

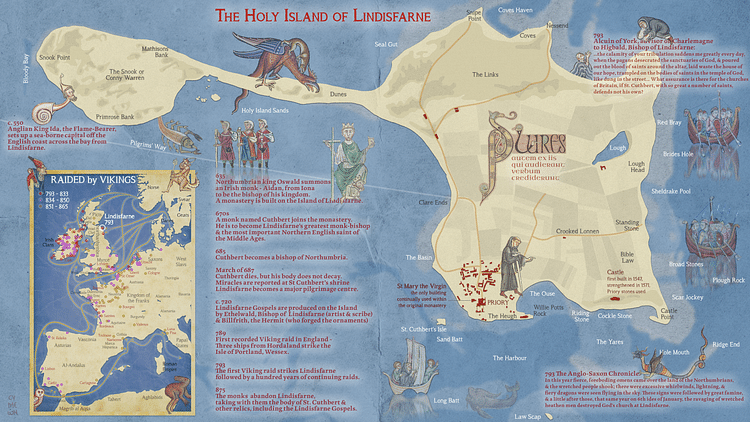

The Book of Kells was produced by monks of St. Columba's order of Iona, Scotland, but exactly where it was made is disputed. Theories regarding composition range from its creation on the island of Iona to Kells, Ireland, to Lindisfarne, Britain. It was most likely created, at least in part, at Iona and then brought to Kells to keep it safe from Viking raiders who first struck Iona in 795, shortly after their raid on Lindisfarne Priory in Britain.

A Viking raid in 806 killed 68 monks at Iona and led to the survivors abandoning the abbey in favor of another or their order at Kells. It is likely that the Book of Kells traveled with them at this time and may have been completed in Ireland. The oft-repeated claim that it was made or first owned by St. Columba (521-597) is untenable as the book was created no earlier than c. 800, but there is no doubt it was produced by later members of his order.

The work is commonly regarded as the greatest illuminated manuscript of any era owing to the beauty of the artwork and this, no doubt, had to do with the purpose it was made for. Scholars have concluded that the book was created for use during the celebration of the mass but most likely was not read from so much as shown to the congregation.

This theory is supported by the fact that the text is often carelessly written, contains a number of errors, and at points certainly seems an afterthought to the illustrations on the page. The priests who would have used the book most likely already had the biblical passages memorized and so would recite them while holding the book, having no need to read from the text.

Scholar Christopher de Hamel notes how, in the present day, “books are very visible in churches” but that in the Middle Ages this would not have been the case (186). De Hamel describes the rough outline of a medieval church service:

There were no pews (people usually stood or sat on the floor), and there would probably have been no books on view. The priest read the Mass in Latin from a manuscript placed on the altar and the choir chanted their part of the daily office from a volume visible only to them. Members of the congregation were not expected to join in the singing; some might have brought their Books of Hours to help ease themselves into a suitable frame of mind, but the services were conducted by the priests. (186)

The Book of Kells is thought to have been the manuscript on the altar which may have been first used in services on Iona and then certainly was at the abbey of Kells. The brightly-colored illustrations and illumination would have made it an exceptionally impressive piece to a congregation, adding a visual emphasis to the words the priest recited while being shown to the people; much in the way one today would read a picture book to a small child.

Appearance & Content

The book measures 13x10 inches (33x25 cm) and is made of vellum pages decorated in painted images which are accompanied by Latin text written in insular script in various colors of ink. It includes the complete gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, and part of John as well as indexes and cross-references, summaries, and commentary. It was originally bound by a cover of gold and jewels which was lost when the manuscript was stolen from the abbey in 1007. The ornate binding, front and back, was torn off by the thieves, which also resulted in the loss of some of the folios at either end, and this may have been when the latter part of the Gospel of John was lost.

It is also possible, however, that John may never have been completely copied. There is evidence that the Book of Kells is an unfinished manuscript. There are blank pages, for example, and some missing illustrations; although these may have been lost rather than never completed. The work was done by three separate anonymous scribes who are identified in the present day only as Hand A, Hand B, and Hand C. It was common for more than one scribe to work on a manuscript – even on a single page of a book – to proofread and correct another's errors or to illuminate a text already copied.

Creation

Monks produced illuminated manuscripts between the 5th and 13th centuries. After the 13th century, professional book-makers emerged to meet the growing demand for literary works. It was a natural outgrowth of the monastic life that monks should be the first copyists and creators of books. Each monastery was required to have a library as dictated by the rules of St. Benedict of the 6th century. Even though it is clear that some monks arrived at these places with their own books, it is equally evident that many others were borrowed from elsewhere and copied.

Monks who worked on books were known as scriptores and worked in rooms called scriptoriums. The scriptorium was a long room, lit only by the light from the windows, with wooden chairs and writing tables. A monk would sit hunched over these tables, which angled upwards to hold manuscript pages, day after day to complete a work. Candles or oil lamps were not allowed in the scriptorium to maintain the safety of the manuscripts as fire was an obvious and significant threat.

Monks were involved in every aspect of book-making from the cultivation of the animals whose skin would be used for the pages, to processing that skin into vellum, and on further to the finished product. Once the vellum was processed, a monk would begin by cutting down a sheet to size. This practice would define the shape of books from that time down to the present day; books are longer than they are wide because the monks needed a taller page to work on.

Once the vellum sheet was prepared, lines would be drawn across it to serve as rules for text and blank spaces left open on the sides and borders for illustrations. The text was written first in black ink between these ruled lines by one monk and then would be given to another to proofread. This second monk would then add titles in blue or red ink and then pass the page on to the illuminator who would add images, color, and the silver or gold illumination. Monks wrote with quill pens and boiled iron, tree bark, and nuts to make black ink; other ink colors were produced by grinding and boiling different natural chemicals and plants.

Illumination

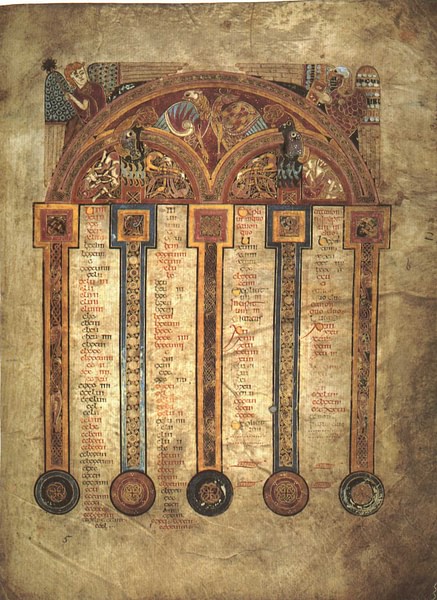

The images in the Book of Kells (and other illuminated manuscripts) are called miniatures. Scholar Giulia Bologna explains:

The term miniature is derived from miniare, which means `to colour in red'; minium is the latin name for cinnabar or mercuric sulphide. This red, used in wall-paintings at Pompeii, was put to common use colouring the initials of early codices, hence its name became the term used to indicate pictures in manuscript books. (31)

The artists who painted these works were known as miniaturists but later as illuminators. The illuminator would begin with a sheet of vellum on which text had usually already been written. The section of the page to be worked on would be rubbed by the monk with clay or isinglass or with "a mixture of ox-bile and egg-albumen or by rubbing the surface with cotton-wool dipped in a diluted glue-and-honey solution" (Bologna, 32). Once the surface was prepared, the monk readied his brushes - which were made of the hair of squirrel tails pressed into a handle - as well as his pens and paints and set to work. Errors in the image were erased by rubbing them away with chunks of bread.

According to Bologna, "we learn of the techniques of illumination from two sources: from uncompleted manuscripts that allow us to observe the interrupted stages of the work and from the directions compiled by medieval authors" (32). The illuminator would begin by sketching an image and then tracing it onto the vellum page. The first layer of paint would be applied to the image and then left to dry; afterwards, other colors were applied. Gold or gold leaf was the first on the page to provide the illumination highlighted by the colors which followed. In this way, the great Book of Kells was produced.

History

Although it is clear how the manuscript was probably made, no consensus has ever been reached on where it was created. Christopher de Hamel writes:

The Book of Kells is a problem. No study of manuscripts can exclude it, a giant among giants. Its decoration is of extreme lavishness and the imaginative quality of its workmanship is quite exceptional. It was probably this book which Giraldus Cambrensis, in about 1185, called “the work of an angel, not of a man”. But in the general history of medieval book production the Book of Kells has an uncomfortable position because really very little is known about its origin or date. It may be Irish or Scottish or English. (21)

However that may be, most scholars agree on either a Scottish or Irish origin for the work and, since the monks of Iona were originally from Ireland, Irish influence is considered most prominent. The Book of Durrow (650-700), certainly created in Ireland and predating the Book of Kells by more than century, shows many of the same techniques and stylistic choices. Thomas Cahill, writing on the development of literacy and book-making in Ireland, comments:

Nothing brought out Irish playfulness more than the copying of the books themselves…they found the shapes of letters magical. Why, they asked themselves, did a B look the way it did? Could it look some other way? Was there an essential B-ness? The result of such why-is-the-sky-blue questions was a new kind of book, the Irish codex; and one after another, Ireland began to produce the most spectacular magical books the world had ever seen. (165)

Cahill goes on to note how the Irish monks combined the letters of the Roman alphabet with their own Ogham script and whatever fancies their imagination leaned them to produce the opening capital letters on the page, the headings, and the borders which framed the miniatures. Wherever the Book of Kells was started or finished, the Irish touch is unmistakable throughout the work.

As noted, it most likely came to Kells from Iona in 806 following the worst of the Viking raids on the island and is known to have been stolen in 1007 when its cover was lost; the text itself was found discarded. It is considered most likely the same book Giraldus Cambrensis so admired at Kildare in the 12th century but, if he is correct about this location, it was back at the abbey of Kells in the same century as land charters pertaining to the abbey were written on some of the pages.

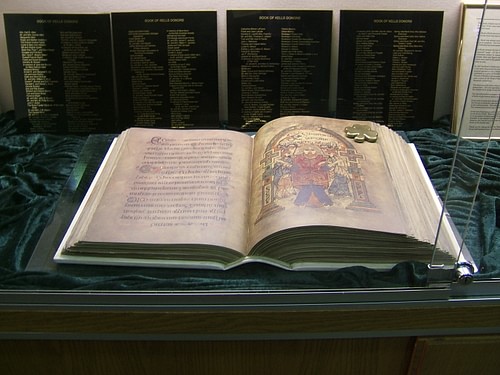

It remained at the abbey until the 17th century when Oliver Cromwell invaded Ireland (1649-1653) and stationed a part of his force at Kells; at this time the manuscript was brought to Dublin for safe-keeping. It came into the hands of the bishop Henry Jones (1605-1682), an alumnus of Trinity College, and Jones donated it to the college's library in 1661 along with the Book of Durrow. The manuscript has been housed at the Trinity library ever since. In 1953 the book was rebound in four separate volumes to help preserve it. Two of these volumes are on permanent display at Trinity College; one showing a page of text and the other a page of illustration.

In 2011 the town of Kells mounted a petition to have at least one of these volumes returned. Arguing that they are the original owners of the manuscript, and citing the over 500,000 visitors who come to Trinity each year to see the work, the town claims that they deserve to share in some of the benefits of tourism that Trinity has enjoyed so long.

The request was denied, however, citing the delicate nature of the manuscript and the inability of Kells to care for it as well as Trinity College. Facsimiles have been made of the Book of Kells for scholars, art historians, and other fields of study but the manuscript itself is no longer loaned or allowed to be handled. The work remains at Trinity where it is displayed in an exhibit featuring additional information on the most famous of the illuminated manuscripts.