The Boston Massacre, or the Incident on King Street, occurred in Boston, Massachusetts, on 5 March 1770, when nine British soldiers fired into a crowd of American colonists, ultimately killing five and wounding another six. The massacre was heavily propagandized by colonists such as Paul Revere and helped increase tensions in the early phase of the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

Background

In the mid-1760s, the Parliament of Great Britain attempted to directly tax the Thirteen Colonies of British North America to raise revenue in the aftermath of the expensive Seven Years' War (1756-1763). Although Parliament believed it was well within its authority, the American colonists disagreed; as subjects of the British Crown, the colonists believed they enjoyed the same rights as all Britons, including the right of self-taxation. Since the colonists were unrepresented in Parliament, they contended that Parliament had no power to directly tax them; prominent colonists like Samuel Adams (1722-1803) of Boston argued that the Americans would be resigning themselves to the status of 'tributary slaves' if they consented to pay the Parliamentary tax (Schiff, 73).

In April 1765, news reached the colonies that Parliament had issued the Stamp Act, a direct tax on all paper documents. The outraged colonists protested the Stamp Act in a variety of ways; the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a series of resolves denouncing the act as a violation of Americans' rights, while colonial merchants began boycotting British imports. However, the most dramatic opposition to the Stamp Act took place in Boston, the capital of the Province of Massachusetts Bay. On 14 August 1765, a mob of Bostonians hanged an effigy of Andrew Oliver, the stamp distributor for Massachusetts, from an elm tree before viciously ransacking his house that evening. Fearing for his life, Oliver resigned the next day, but the mob was unsatisfied; on 26 August, it attacked the home of Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts, stealing all movable goods from the house. These riots were celebrated throughout the colonies; the Sons of Liberty, a loosely organized group of colonial political agitators, dated its founding from the riots, while the elm tree on which Oliver's effigy was hanged became known as Boston's 'Liberty Tree'.

Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in March 1766, but the colonists barely had time to celebrate before a new set of taxes and regulations, the Townshend Acts, were passed by Parliament between 1767 and 1768. These acts imposed new duties on goods such as glass, paint, and tea, and required a Board of Commissioners to set up headquarters in Boston to oversee the collection of the taxes. When the five commissioners arrived in Boston in November 1767, they were greeted by a hostile crowd carrying effigies and wearing labels that read, "Liberty & Property & no Commissioners" (Middlekauff, 163). Nor did the commissioners receive a much warmer welcome from Boston's leading citizens; John Hancock (1737-1793), one of the city's wealthiest merchants, refused to allow his Cadet Company, a military organization he operated, to participate in a parade held to welcome the commissioners. Eager to put men like Hancock in his place, the commissioners seized Hancock's sloop, the Liberty, on 10 June 1768, on the pretext that the Liberty had transported contraband goods and that its captain had threatened a tax collector.

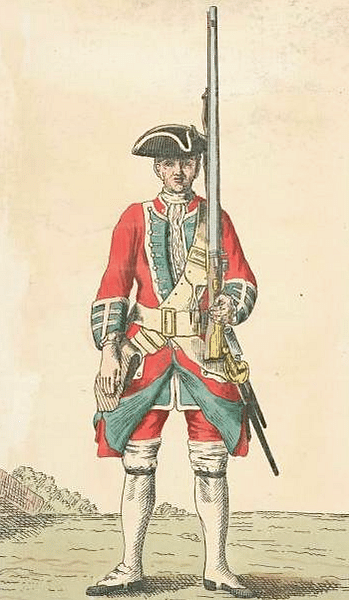

When British sailors arrived to take possession of the Liberty, they were greeted by a mob, who were already angry that the British had been impressing Boston sailors into the Royal Navy. A brawl broke out along the docks that soon blossomed into a city-wide riot, as thousands of colonists roamed the streets beating up tax collectors and attacking the commissioners' homes. The royal officials had to flee to Castle Island, a fortified island in Boston Harbor, to escape the violence. To restore order, General Thomas Gage, commander-in-chief of all British forces in North America, decided to move troops into Boston. Roughly 2,000 British soldiers, mostly from the 29th and 14th regiments, were loaded into transports and carried from Halifax to Boston, arriving in the town on 1 October 1768. A manifestation of Britain's imperial power, the red-coated soldiers disembarked and marched to Boston Common, their fixed bayonets gleaming in the sunlight.

A Garrison Town

The British force was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William Dalrymple of the 14th Regiment, who sent a request to Boston officials to supply quarters and provisions for his men. The colonial authorities refused, telling Dalrymple that there were ample barracks on Castle Island, and until those barracks reached capacity, they would not pay for any British soldiers to be quartered in Boston itself. After several days of fruitless negotiations, during which time the British regiments remained stuck on the ships, Colonel Dalrymple finally had enough. He ordered all his men into Boston; if the stubborn local officials refused to provide quarters, Dalrymple would simply camp his men on Boston Common.

The majority of the 29th Regiment did indeed set up camp on the common, pitching their tents amongst the town's livestock, while the 14th Regiment got slightly luckier and moved into Faneuil Hall, drafty and cramped though it was. With the rapid approach of winter, these accommodations could only last for so long, and within weeks, the troops had moved into warehouses, inns, and other buildings rented out by private citizens. If the Bostonian officials had hoped to make a point by refusing to pay for the army's lodgings, Colonel Dalrymple had made a point of his own: until Boston cleaned up its act, the soldiers were here to stay. For the next year and a half, this was an unavoidable fact of life, as Bostonians and soldiers lived and worked side by side.

The enmity between the colonists and the soldiers was apparent from the beginning. The daily sight of armed redcoats patrolling their streets and standing guard outside public buildings was almost too much to bear for the Bostonians, who were unused to having their personal liberties challenged in such a way. The colonists particularly hated having their comings and goings challenged by British sentries, posted on major streets. Though it was standard procedure for sentries posted anywhere in Britain to challenge passers-by, the Bostonians resented this and often chose not to respond; this sometimes led to scuffles that would more than likely end with the unruly colonist being hit with a musket butt. Matters were not helped by the fact that off-duty soldiers often drank to excess, leading to several incidents where colonists were taunted or threatened by drunken soldiers.

The longer the British soldiers remained in Boston, the more they integrated themselves within the community, much to the chagrin of some of their new neighbors. Army regulations at the time allowed off-duty soldiers to find work at civilian jobs to supplement their military incomes. These soldiers were often willing to work below the going rate of pay, leading them to take jobs that Bostonian laborers felt belonged to them. Some British soldiers courted and even married Boston women, a union unacceptable to any self-respecting Son of Liberty. Bostonian Judge Richard Dana, for instance, went so far as to prevent his daughter from leaving the house, for fear that she would fraternize with a soldier.

At the same time, many Bostonians took pity on the British soldiers, especially after witnessing the harsh discipline they were subjected to. It was not uncommon for soldiers to receive hundreds of lashes for infractions that the colonists considered insignificant; one Private Daniel Rogers was sentenced to 1,000 lashes from a cat-o'-nine-tails after deserting his post to visit his family in nearby Marshfield. Rogers received 170 lashes before losing consciousness; he was spared from enduring the rest of his punishment after Bostonians petitioned Colonel Dalrymple to have mercy on him.

Private Richard Eames, another deserter, was not so lucky; after being caught on a farm in Framingham, Eames was executed by firing squad on Boston Common. Such actions horrified the colonists and convinced them of the cruelty of the British army. By April 1769, an average of one British soldier was deserting every two and a half days, a rate that alarmed military officials, who suspected that the colonists were aiding runaway soldiers. They were not wrong, as some Bostonians were actively encouraging the soldiers to desert; the rate of desertion added to the propaganda of the Sons of Liberty, who wasted no time using it to show that American life was preferable to life in the British army.

Murder of Christopher Seider

As tensions rose between Bostonians and British soldiers, colonial merchants' boycotts of the Townshend Acts remained in force. However, some merchants, like Theophilus Lillie, refused to comply with the boycotts; Lillie argued that the Bostonians had no more right to force him to comply with a boycott than Parliament had to tax the colonies. Lillie's outspokenness marked him as a target for Boston's liberty faction; on 22 February 1770, a crowd primarily comprised of young boys carried a sign to his shop that read "Importer", singling Lillie out as a violator of the boycott.

One of Lillie's neighbors, Ebenezer Richardson, attempted to shoo the crowd away and tear down the sign. Richardson was well-known as an informant for royal officials, and the crowd quickly redirected its anger toward him. The crowd followed him home and surrounded his house, with some participants shouting: "Come out you damn son of a bitch, I'll have your heart and liver out" (Middlekauff, 208). Richardson felt his life was in danger, and after some of the crowd began breaking his windows, he fired a gun into the mass of people. One boy was wounded and another, eleven-year-old Christopher Seider, was killed. Richardson was arrested and eventually convicted of murder, although he was ultimately freed when the king pardoned him.

The murder of young Seider only served to pour gas on the fire. Richardson was not a British soldier, but his actions increased the town's disdain of royal officials and of the soldiers, who were after all there to see those officials' policies carried out. The Sons of Liberty organized Seider's funeral, which was attended by thousands of Bostonians.

Brawl at Gray's Ropewalk

In the weeks following Seider's funeral, fights between soldiers and Bostonians became more frequent. The most consequential of these occurred on 2 March, when an off-duty soldier walked into John Gray's Ropewalk searching for a job. When the soldier asked a ropemaker if he had any work, the ropemaker responded that he did, inviting the soldier to "clean my shithouse" (Middlekauff, 209). The soldier took this as an insult and struck the ropemaker; their fight quickly turned into a street brawl as more soldiers and Bostonians joined the fray. The following day, several more fights broke out, often involving clubs and cudgels. With tensions in the city at an all-time high, it was only a matter of time before blood would be spilled.

The Incident

At 8 p.m. on 5 March 1770, Private Hugh White of the 29th Regiment was standing guard outside the customshouse on King Street. As he stood at his post, Private White overheard Edward Gerrish, an apprentice, insult an army officer by saying that there were "no gentlemen among the officers of the 29th" (Middlekauff, 210). White took it upon himself to discipline the lad by giving him a blow on the ear; Gerrish also appears to have been struck by an off-duty soldier standing nearby. Word that Gerrish had been accosted by a British soldier quickly spread and within 20 minutes, a crowd of angry Bostonians had surrounded Private White. The crowd hurled verbal abuse at the soldier; when White threatened to run them through with his bayonet if they did not disperse, the crowd started throwing snowballs and chunks of ice. White backed up to the door of the customshouse, where he attempted to hold back the mob singlehandedly.

Captain Thomas Preston watched with mounting unease. Preston was in command that evening and was aware that he would have to act if the crowd did not clear off on its own. It soon became apparent that Preston would have no such luck; the city's church bells began to ring, which usually meant that there was a fire. At first, scores of well-meaning civilians showed up carrying buckets of water to help put out the nonexistent flame, then others arrived, carrying clubs and even swords, their anger fueled by rumors that British soldiers meant to cut down the Liberty Tree. Preston decided to act; he ordered six privates and a corporal to follow him into the crowd, intending to rescue White. Preston and the soldiers easily pushed their way through the crowd but found themselves trapped when the Bostonians filled in behind them.

With the soldiers now trapped by the mob, Preston ordered his men to form a semicircle, their backs to the customshouse, and load their muskets. For 15 tense minutes, the standoff continued; some of the redcoats were recognized by the colonists as having participated in the brawl outside Gray's Ropewalk, leading tensions to increase. By this point, the crowd numbered 300-400, and angry Bostonians continued to throw snowballs and pieces of ice at the soldiers. Some colonists began striking the soldiers' muskets with sticks, daring them to fire. Captain Preston positioned himself in front of his men, at which point a colonist warned him to "take care of your men for if they fire, your life must be answerable." To this, Preston simply replied, "I am sensible of it" (Middlekauff, 211). An innkeeper named Richard Palmes then pulled Preston aside to inquire if the soldiers' muskets were loaded; Preston responded that they were but assured Palmes that they would not fire.

As Preston and Palmes spoke, a piece of ice flung from the crowd hit Private Hugh Montgomery, causing him to slip and fall down. Montgomery staggered to his feet before discharging his musket into the crowd, despite having received no order to do so. After Montgomery's shot rang out, there was a short pause before the other soldiers opened fire. Eleven men were hit. Three died instantly including ropemaker Samuel Gray, mariner James Caldwell, and Crispus Attucks, a mixed-race sailor of African and Native American descent. Samuel Maverick, a 17-year-old apprentice, became the fourth victim when he died of his wounds the next morning, while Patrick Carr, an Irish immigrant, sustained a wound in the abdomen and lingered for two weeks before finally succumbing.

Trials

Although the crowd was scattered by the shooting, it had reformed within hours and began prowling the streets calling for vengeance against Captain Preston and his men. Lieutenant Governor Hutchinson knew he had to de-escalate the situation and had Preston and the other eight soldiers arrested the following day; the British soldiers were indicted for murder. Despite the rage that many Bostonians felt toward the British army, Boston officials were aware that they needed to ensure a fair trial, lest they give the army reason to retaliate. To achieve this purpose, the trials of Preston and his men were delayed until autumn, to give tempers time to cool off and to have a better chance of finding an impartial jury. The soldiers would be defended by John Adams (1735-1826), a Bostonian lawyer destined to become the second President of the United States. Although Adams was an ardent Patriot, he firmly believed that everyone was entitled to a fair trial, leading him to accept the case.

Captain Preston was tried first, in the last week of October 1770. After calling many witnesses who gave often contradictory accounts, Adams was able to give the jury reasonable doubt that Preston had given the order to fire, and the captain was acquitted. The other eight soldiers were tried together a month later; Adams told the jury that they had been accosted by a violent mob and had only fired out of self-defense. This mob, according to Adams, was comprised mainly of "molattoes, Irish teagues, and Jack Tars [i.e., sailors]" (Zabin, 216). By painting the mob as consisting mostly of those considered to be outsiders, he successfully deflected the blame from both the 'upstanding' Bostonians and the soldiers. Again, Adams achieved his goal; six soldiers were fully acquitted. Two were convicted of manslaughter and had their thumbs branded, a light punishment compared with the penalty of death that was originally on the table.

Conclusion

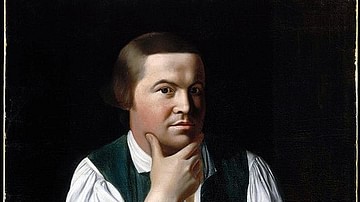

Although the soldiers were lightly punished, the people of Boston would not soon forget that five of their number had been killed in cold blood by soldiers of His Majesty's army. Tensions between colonists and redcoats only increased after the incident; a famous engraving by Paul Revere (1735-1818), based on an original by Henry Pelham, depicts the line of British soldiers calmly firing a volley into the crowd, Captain Preston standing behind them with his sword raised. While this is clearly a propagandized version of events, it became accepted by many colonists who began referring to the incident as the 'Boston Massacre'.

The massacre holds an important place in the story of the American Revolution, marking the first instance in which blood was spilled over the cause of American liberty. More colonists began to view Britain, and even the king, with distrust; after the massacre, the lines between American 'Loyalists', or supporters of Britain, and 'Patriots', or supporters of the Liberty cause, became more defined, helping to hasten the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and, ultimately, the drafting of the American Declaration of Independence.