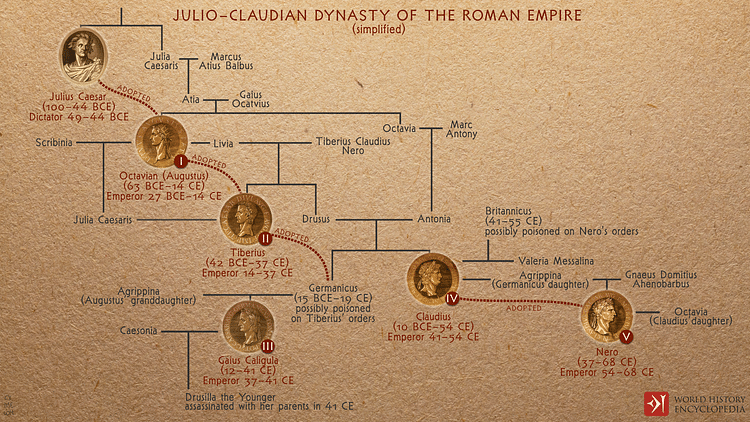

Britannicus (41-55 CE) was the second child and only son born to the Roman emperor Claudius (r. 41-54 CE) and Valeria Messalina (c. 20-48 CE). Seen as a threat by Claudius' fourth wife, Agrippina the Younger (15-59 CE), and her son, the future Nero (r. 54-68 CE), Britannicus was poisoned the night before his 14th birthday.

Early Childhood

Born on 12 February 41 CE, he was originally named Tiberius Claudius Caesar Germanicus; the name Britannicus was added after his father's invasion of Britain. In his The Twelve Caesars, the ancient historian Suetonius (69 to 130/140 CE) wrote, "Claudius would often pick little Britannicus up and show him to the troops or to the audience at the games either seated on his lap or held at arm's length" (197) Claudius had a son by his first wife Urgulanilla, but the boy died accidentally before coming of age, and Britannicus became the obvious choice to assume the purple upon the emperor's death. However, this would soon change when Claudius married his niece Agrippina the Younger (15-59 CE). The emperor's new wife brought with her a hidden agenda; she had high aspirations for her son, the future emperor Nero (r. 54-68 CE).

Agrippina the Younger was the daughter of Emperor Tiberius' (r. 14-37 CE) nephew Germanicus (15 BCE to 19 CE) and Agrippina the Elder (14 BCE to 33 CE), making her the great-granddaughter of Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE). Her marriage to Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus produced one son Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, the future Nero (b. 37 CE). Gnaeus, who died when Nero was three, was extremely violent and was described by his contemporaries as "a despicable character." Two years after Domitius' birth, Agrippina was exiled by her brother Caligula (r. 37-41 CE). After Caligula's assassination in 41 CE, one of Claudius' first acts was to recall her. Her strong ties to the Julio-Claudians would pose a serious challenge to young Britannicus' position as the emperor's heir and, unfortunately for Britannicus, the highly aggressive Agrippina would stop at nothing until little Domitius upended his position. According to Matthew Dennison in his The Twelve Caesars, Agrippina "was not distracted by bodily appetites; arrogance and an undistracting focus steadied her performance." (156)

In 40 CE Domitius' father died of dropsy. Upon her return to Rome from exile, the widowed Agrippina married Gaius Passienus Crispus, who had recently divorced Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus' sister Domitia. The marriage ended before 47 CE, possibly due to poisoning. Agrippina inherited his vast wealth, making her extremely rich. Widowed twice, she set her sights on husband number three: her uncle Claudius. Claudius showed little interest in obtaining another wife; there was still strong competition for the old emperor: Aelia Paetina (his second wife) and Lollia Paulina (Caligula's third wife). Lollia would later be exiled on the orders of Agrippina where a suicide would soon follow. However, Claudius' financial secretary Marcus Pallas favored Agrippina, and on 1 January 49 CE, she became Claudius' fourth wife.

Having married the emperor, her next objective was to secure the adoption of her son, and on 28 February 50 CE, Lucius Domitius became Nero Claudius Drusus Germanicus Caesar. Suetonius wrote, "In his last years, Claudius made it pretty plain that he repented of having married Agrippina and adopted Nero" (204). Realizing, the possible danger posed by Nero and his mother, Claudius told his son repeatedly "to grow up quickly." With the adoption of Nero secured, Agrippina turned her attention to the one serious obstacle to her son becoming the emperor: Britannicus.

Rivalry with Nero

Messalina had initially never entertained the thought that Domitius was a potential threat to her son's future, but she soon realized that she was wrong. At nine years old, Domitius was three years older than Britannicus, and since both boys had 'princely blood', Messalina wanted to ensure that her son would inherit the throne. According to historian Anthony Everitt in his book Nero, assassins were sent to the sleeping boy's bedroom while he was taking a nap with orders to strangle him, but they failed either by being betrayed or by interception. A second attempt saw a snake placed in Domitius' bedroom, but it slipped away. Now, Messalina was long dead; Agrippina was married to Claudius, and it was Britannicus who posed a threat.

Agrippina – Dennison called her a "scheming stepmother" – realized she had to establish a prominent image for her son. Between 50 and 53 CE, Nero married Octavia (Britannicus' sister), assumed the toga virilis of manhood one year early, and was named princeps iuventutis or Prince of Youth. Things could only get worse for Britannicus.

Shortly after Nero was adopted, Britannicus addressed him as Domitius. Nero felt dishonored, and his mother was incensed. She blamed his tutors and teachers along with his loyal officers of the guard. The tutors, his slaves, and even the guards were all removed. Agrippina surrounded him with those loyal to her, not him. She even kept him out of the public eye. The outlook appeared very bleak for the boy. Tacitus wrote that "a stepmother's treacherous schemes were convulsing the whole imperial palace" (282).

Death of Claudius

With Nero becoming the obvious heir to the throne, Agrippina's next goal was to rid herself of a husband. Time was of the essence. Britannicus was one year away from turning 14 and receiving his toga virilis. Considering the various alternatives, she realized she could not wait for Claudius to die of natural causes. She needed something that would kill him quickly. The obvious answer was poison – rumor had that she had already used it on her second husband. The most-used poison at the time was a vegetable derivative, possibly a belladonna alkaloid like henbane, mandrake, and nightshade, as well as hemlock, aconite, and yew. And one of the best at the craft of poisoning was Locusta. Although usually protected by her more notable clients, she had been arrested and found guilty of murder. Acting quickly, Agrippina rescued her from prison. The ideal opportunity to poison Claudius came at a dinner party on 13 October 54 CE.

The plan was fairly easy. Poison would be added to the emperor's favorite dish, mushrooms, by his usual food taster Halotus. Some sources maintain that Agrippina replaced the emperor's regular taster with one of her choosing. Accounts vary as to what happened after the emperor ate the mushrooms. According to one, Claudius reacted quickly – sweating, cramping, and gasping for air. With a severe case of diarrhea, the emperor was escorted away where he suffered throughout the night, dying before dawn. Few assumed anything suspicious of his reaction, for he often overate and drank. To show there was nothing wrong with the mushrooms, Agrippina ate a harmless one. The account often accepted has the emperor's doctor, Xenophon, attend to him, inserting a poisoned feather down his throat; he died immediately. Whether or not Nero played a part in the poisoning is questionable; however, he was heard saying that mushrooms were "the food of the gods." The following day Nero was proclaimed emperor by the Praetorian Guard. Instead of being rewarded, Locusta was arrested with orders to be bludgeoned to death, but Nero, realizing she might be useful in the case of Britannicus, gave her a stay of execution.

Death of Britannicus

It did not take the new emperor long to make plans to rid himself of the two remaining thorns in his side: Britannicus and his mother. Agrippina had taught him well: poison was the best choice to eliminate Britannicus. An early attempt – one driven by jealousy and fear – had failed. Suetonius wrote that Nero tried to poison Britannicus "no less because he was jealous of his (singing) voice ... than for fear that the common people might be less attached to Claudius' adopted son than to is real one" (226). On the first attempt, the poison, provided by Locusta, proved only to give Britannicus diarrhea. Nero was incensed. He threatened her with execution and then beat her. A stronger dose was prepared, and this time it was tested on a pig. The poor pig died immediately. On 12 February 55 CE, Britannicus would celebrate his 14th birthday and receive his toga virilis. On that day, he would present himself as a serious threat to Nero. By now, Agrippina had grown wary of Nero's sudden burst of independence and unexpectedly viewed Claudius' son in a different light as a worthy heir.

On 11 February, Nero held a dinner party. Besides the usual guests, Britannicus' close friend Titus (r. 79-81 CE), the son of Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE), was also present. Britannicus was served a drink which had been test-tasted, but it burnt his tongue. The taster apologized and removed the drink. It was cooled and returned to the boy, but it had not been retested. When Britannicus took a sip, he convulsed and could neither speak nor breathe. He was taken away, and dinner resumed. Nero claimed it was only another attack of epilepsy. Tacitus described the young heir's death:

A cup as yet harmless, but extremely hot and already tasted was handed to Britannicus; then, on his refusing it because of its warmth, poison was poured in with some water and then so penetrated his entire frame that he lost alike voice and breath. (293)

According to Suetonius' account, he died at the first taste. Those in attendance were shocked; some panicked and ran off. Nero wasted little time; Britannicus was buried that same night in the Mausoleum of Augustus. Oddly, the funeral pyre had been prepared in advance. Claims of epilepsy were quickly proven wrong. His body was dark and blotchy. To mask them, the blotches were covered with gypsum, but the heavy rain washed it away, exposing the truth. Everitt wrote that Britannicus' dark skin could suggest arsenic.

Aftermath

For her part in the poisoning, Locusta was given estates in the country and immunity. Supposedly, Agrippina had struggled to hide her terror and confusion at Britannicus' death. It was obvious she had not been warned. She realized she had lost her only remaining refuge and she could be next. Although she was still determined to continue her control over her son, she saw her influence on her son was gradually weakening. Nero gave her little respect and did everything possible to annoy his mother. He was now the emperor and no longer needed his domineering mother. Several attempts were made on her life, but all of them failed. Word of various plots reached Agrippina, but she ignored them all. In the end, guards were sent – it was supposed to look like suicide – but a centurion drew his sword and, with a single strike to her stomach, killed her. Nero was now free to do as he wished, but he would be haunted by his mother's death for the rest of his life.