Byzantine art (4th - 15th century CE) is generally characterised by a move away from the naturalism of the Classical tradition towards the more abstract and universal, there is a definite preference for two-dimensional representations, and those artworks which contain a religious message predominate. However, by the 12th century CE Byzantine art has become much more expressive and imaginative, and although many subjects are endlessly recycled, there are differences in details throughout the period. Whilst it is true that the vast majority of surviving artworks are religious in subject, this may be a result of selection in subsequent centuries as there are abundant references to secular art in Byzantine sources and pagan subjects with classical iconography continued to be produced well into the 10th century CE and beyond. Using bright stones, gold mosaics, lively wall paintings, intricately carved ivory, and precious metals in general, Byzantine artists beautified everything from buildings to books, and their greatest and most lasting legacy is undoubtedly the icons which continue to decorate Christian churches around the world.

Influences

As Byzantium was the eastern branch of the Roman Empire in its earliest phase, it is not surprising that a strong Roman, or more precisely, Classical influence predominates Byzantine output. The Roman tradition of collecting, appreciating, and privately displaying antique art also continued amongst the wealthier classes of Byzantium. Byzantine art is at once both unchanging and evolutionary, themes such as the Classical traditions and conventional religious scenes were reworked for century after century, but at the same time, a closer examination of individual works reveals the details of an ever-changing approach to art. As with modern cinema that regularly remakes a familiar story with the same settings and the same characters, Byzantine artists worked within the limits of the practical end function of their work to make choices on how best to present a subject, what to add and omit from those new influences which came along, and, by the end of the period, to personalize their work as never before.

It is perhaps important to remember that the Byzantine Empire was much more Greek than Roman in many aspects and Hellenistic art continued to be influential, especially the idea of naturalism. At the same time, the geographical extent of the empire also had its implications for art. In Alexandria the more rigid (and for some, less elegant) Coptic style took off from the 6th century CE, replacing the predominant Hellenistic style. Half-tone colours were avoided and brighter ones were favoured while figures are squatter and less realistic. Another area of artistic influence was Antioch where the 'orientalizing' style was adopted, that is the assimilation of motifs from Persian and central Asian art such as ribbons, the Tree of Life, ram's heads, and double-winged creatures, as well as the full frontal portraits which appear in the art of Syria. In turn, the art of these great cities would influence that produced in Constantinople, which became the focal point of an art industry that spread its works, methods, and ideas throughout the Empire.

The Byzantine Empire was continuously expanding and shrinking over the centuries, and this geography influenced art as new ideas became more readily accessible over time. Ideas and art objects were continuously spread between cultures through the medium of royal gifts to fellow rulers, diplomatic embassies, religious missions, and souvenir-buying wealthy travellers, not to mention the movement of artists themselves. From the early 13th century CE, for example, Byzantium was influenced by much greater contact with western Europe, just as it had been when the Byzantines were more present in Italy during the 9th century CE. The influence went in the other direction, too, of course, so that Byzantine artistic ideas spread, notably outwards from such outposts as Sicily and Crete from where Byzantine iconography would go on to influence Italian Renaissance art. So, too, in the north-east, Byzantine art influenced such places as Armenia, Georgia, and Russia. Finally, Byzantine art is still very much alive as a strong tradition within Orthodox art.

Artists

In the Byzantine Empire, there was little or no distinction between artist and craftsperson, both created beautiful objects for a specific purpose, whether it be a box to keep a precious belonging or an icon to stir feelings of piety and reverence. Some job titles we know are zographos and historiographos (painter), maistor (master) and ktistes (creator). In addition, many artists, notably those who created illustrated manuscripts, were priests or monks. There is no evidence that artists were not women, although it is likely they specialised in textiles and printed silks. Sculptors, ivory workers, and enamelists were specialists who had acquired years of training, but in other art forms, it was common for the same artist to produce manuscripts, icons, mosaics, and wall paintings.

It was rare for an artist to sign their work prior to the 13th century CE, and this may reflect a lack of social status for the artist, or that works were created by teams of artists, or that such personalization of the artwork was considered to detract from its purpose, especially in religious art. Artists were supported by patrons who commissioned their work, notably the emperors and monasteries but also many private individuals, including women, especially widows.

Frescos & Paintings

Byzantine Christian art had the triple purpose of beautifying a building, instructing the illiterate on matters vital for the welfare of their soul, and encouraging the faithful that they were on the correct path to salvation. For this reason, the interiors of Byzantine churches were covered with paintings and mosaics. The large Christian basilica building, with its high ceilings and long side walls, provided an ideal medium to send visual messages to the congregation, but even the most humble shrines were often decorated with an abundance of frescoes. The subjects were necessarily limited - those key events and figures of the Bible - and even their positioning became conventional. A depiction of Jesus Christ usually occupied the central dome, the barrel of the dome had the prophets, the evangelists appear on the joins between vault and dome, in the sanctuary is the Virgin and child, and the walls have scenes from the New Testament and the lives of the saints.

Besides walls and domes, small painted wooden panels were another popular medium, especially in the late-Empire period. Literary sources describe small portable portrait paintings which were commissioned by a wide range of people from bishops to actresses. Paintings for manuscripts were also a valued outlet for painting skills, and these cover both religious subjects and historical events such as coronations and famous battles.

Fine examples of the more expressive and humanistic style prevalent from the 12th century CE are the 1164 CE wall paintings in Nerezi, Macedonia. Showing scenes from the cross, they capture the despair of the protagonists. From the 13th century CE, individuals are painted with personality and there is more attention to detail. The Hagia Sophia in Trabzon (Trebizond) has whole galleries of such paintings, dated to c. 1260 CE, where the subjects seem to have been inspired by real-life models. There is also a more daring use of colour for effect. A good example is the use of blues in The Transfiguration, a manuscript painting in the theological works of John VI Cantacuzenus, produced 1370-1375 CE and now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. On a larger scale, this combination of bold colours and fine details is best seen in the wall paintings of the various Byzantine churches of Mistra in Greece.

Icons

Icons - representations of holy figures - were created for veneration by Byzantine Christians from the 3rd century CE. They are most often seen in mosaics, wall paintings, and as small artworks made from wood, metal, gemstones, enamel, or ivory. The most common form was small painted wooden panels which could be carried or hung on walls. Such panels were made using the encaustic technique where coloured pigments were mixed with wax and burned into the wood as an inlay.

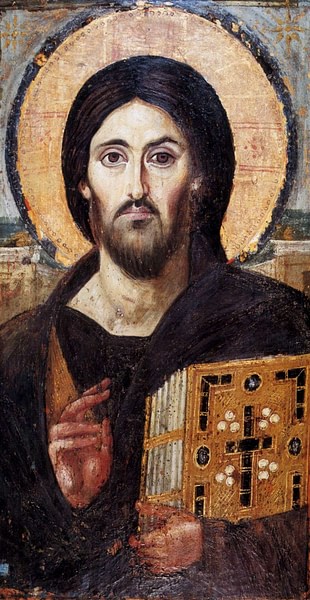

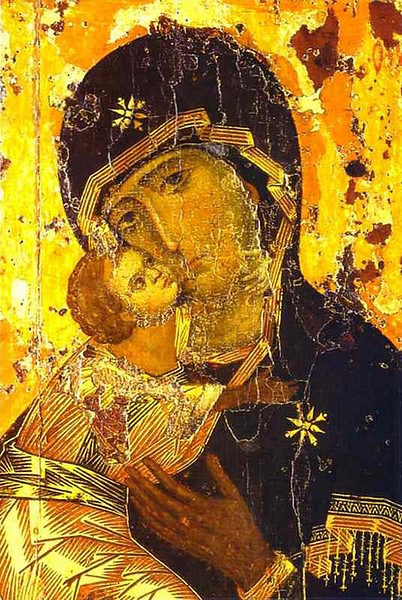

The subject in icons is typically portrayed full frontal, with either the full figure shown or the head and shoulders only. They stare directly at the viewer as they are designed to facilitate communication with the divine. Figures often have a nimbus or halo around them to emphasise their holiness. More rarely, icons are composed of a narrative scene. The artistic approach to icons was remarkably stable over the centuries, but this should not perhaps be surprising as their very subjects were meant to present a timeless quality and instil a reverence on generation after generation of worshippers - the people and fashions might change but the message did not.

Some of the oldest surviving Byzantine icons are to be found in the Monastery of Saint Catherine on Mount Sinai. Dating to the 6th century CE and saved from the wave of iconoclasm which spread through the Byzantine Empire during the 8th and 9th century CE, the finest show Christ Pantokrator and the Virgin and Child. The Pantokrator image - where Christ is in the classic full frontal pose and is holding a Gospel book in his left hand and performing a blessing with his right - was probably donated by Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) to mark the monastery's foundation.

By the 12th century CE, painters were producing much more intimate portraits with more expression and individuality. The icon known as the Virgin of Vladimir, now in the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, was painted in Constantinople c. 1125 CE and is an excellent example of this new style with its tender representation of the child pressing his cheek against his mother.

Mosaics

The majority of surviving wall and ceiling mosaics depict religious subjects and are to be found in many Byzantine churches. One of their characteristics is the use of gold tiles to create a shimmering background to the figures of Christ, the Virgin Mary and saints. As with icons and paintings, the portraiture follows certain conventions such as a full frontal view, halo, and general lack of suggested movement. The Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (Istanbul) contains the most celebrated examples of such mosaics while one of the most unusually striking portraits in the medium is that of Jesus Christ in the dome of Daphni in Greece. Produced around 1100 CE, it shows Christ with a rather fierce expression which is in contrast to the usual expressionless representation.

The mosaics of the Great Palace of Constantinople, which date to the 6th century CE, are an interesting mix of scenes from daily life (especially hunting) with pagan gods and mythical creatures, highlighting, once again, that pagan themes were not wholly replaced by Christian ones in Byzantine art. Another secular subject for mosaic artists was emperors and their consorts, although these are often portrayed in their role as head of the Eastern Church. Some of the most celebrated mosaics are those in the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy, which date to the 540s CE. Two glittering panels show Emperor Justinian I and his consort Empress Theodora with their respective entourages.

Byzantine mosaic artists were so famous for their work that the Arab Umayyad Caliphate (661-750 CE) employed them to decorate the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Great Mosque of Damascus. Finally, just as in painting, in the 13th and 14th century CE, the subjects in mosaics become more natural, expressive and individualised. Excellent examples of this style can be seen in the mosaics of the Church of the Saviour, Chora, Constantinople.

Sculpture

Realistic portrait sculpture was a characteristic of later Roman art, and the trend continues in early Byzantium. The Hippodrome of Constantinople was known to have bronze and marble sculptures of emperors and popular charioteers, for example. Ivory was used for figure sculpture, too, although only a single free-standing example survives, the Virgin and Child, now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Marble and limestone sarcophagi were another outlet for the sculptor's craft. After the 6th century CE, though, three-dimensional portraits are rare, even for emperors, and sculpture reached nowhere near the popularity it had in antiquity.

Minor Arts

Byzantine artists were accomplished metalsmiths, while enamelling was another area of high technical expertise. A superb example of the use of both skills combined is the c. 1070 CE chalice in the Treasury of Saint Mark's, Venice. Made with a semi-precious stone body and gold stem, the cup is decorated with enamel plaques. Cloisonné enamels (objects with multiple metal-bordered compartments filled with vitreous enamel) were extremely popular, a technique probably acquired from Italy in the 9th century CE. Silver plates stamped with Christian images were produced in large numbers and used as a domestic dinner service. A final use of metals is coinage, which was a medium for imperial portraiture and, from the 8th century CE, images of Jesus Christ.

Bibles were made with beautifully written text in gold and silver ink on pages dyed with Tyrian purple and beautifully illustrated. One of the best surviving examples of an illustrated manuscript is the Homilies of Saint Gregory of Nazianzus, produced 867-886 CE and now in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris. Books, in general, were often given exquisite covers using gold, silver, semi-precious stones, and enamels. Reliquaries - containers for holy relics - were another avenue for the decorative arts.

Portable objects were very often decorated with Christian images, and these include such everyday items as jewellery boxes, ivories, jewellery pieces, and pilgrim tokens. Objects made from ivory such as panels and boxes were a particular speciality of Alexandria. Panels were used to decorate almost anything but especially furniture. One of the most celebrated examples is the throne of Maximian, Archbishop of Ravenna (545-553 CE), which is covered in ivory panels showing scenes from the lives of Joseph, Jesus Christ and the Evangelists. Textiles - of wool, linen, cotton, and silk - was another medium for artistic expression, where designs were woven into the fabric or printed by dipping the cloth in dyes with some parts of the cloth covered in a resistor to create the design.

Finally, Byzantine pottery has largely escaped public notice, but potters were accomplished in such techniques as polychrome (coloured scenes painted on a white background and then given a transparent glaze) - a technique passed on to Italy in the 9th century CE. Designs were sometimes incised and given coloured glazes, as in the 13th-14th century CE fine plate showing two doves, now in the Collection David Talbot Rice at the University of Edinburgh. Common shapes included plates, dishes, bowls, and single-handled cups. Tiles were often painted with representations of holy figures and emperors, sometimes several tiles making up a composite image.