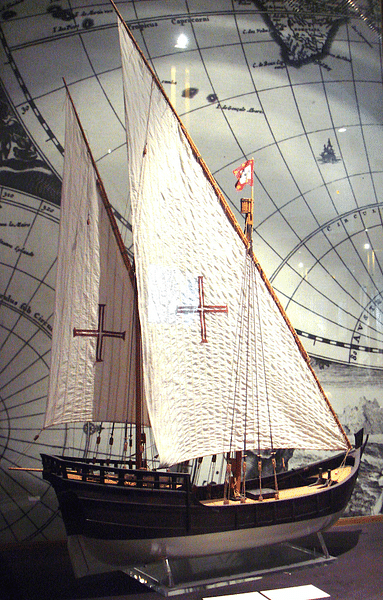

The caravel (caravela in Spanish and Portuguese), was a type of medium-sized ship which, with its low draught and lateen or triangular sails, made it ideal for exploration from the 15th century onwards. Fast, manoeuvrable, and only needing a small crew to sail, the caravel was a mainstay of the Age of Exploration as European nations crossed oceans previously unknown to them.

Design

The caravel sailing vessel was developed from a type of Portuguese fishing boat in the mid-15th century as Prince Henry the Navigator of Portugal (aka Infante Dom Henrique, 1394-1460) looked to explore the world and gain access to distant trade networks. At Sagres on the southern tip of Portugal, Henry had assembled a team of experts in cartography, navigation, astronomy, and ship design, and charged them with coming up with a vessel capable of exploring the high seas. Before this committee got their heads together and developed the caravel design, European sailing vessels depended on either teams of rowers or fixed sails or both for their propulsion; the square-rigged barca being the most common.

The early caravels weighed no more than 80 tons, tiny compared to the ships of later exploration like William Bligh's HMS Bounty (215 tons) and James Cook's HMS Endeavour (370 tons). Later versions did increase to 100-150 tons. The caravel had a stern rudder and a raised forecastle and sterncastle. Caravels had a typical length-to-beam ratio of 3.5:1 with a shallow draught. It was also highly manoeuvrable and fast. All of these characteristics made the caravel ideal for exploring unfamiliar waters and coastal shallows where larger ships might easily have become stranded on sandbanks or damaged by rocks. At the same time, the caravel could cope with the tremendous waves and storms of the High Seas.

A caravel usually had two or three masts (and much more rarely four), and these were equipped with lateen sails. The lateen sail was triangular and the name derives from ‘Latin’ even if it was inspired by the sails of Arab sailing vessels, particularly the dhow with its single lateen sail. Previously, sailing ships using a square sail could only sail with a direct wind behind them, but flexible lateen sails permitted a vessel to sail within five points off the wind and even to tack (move in a forward zig-zag) against a headwind. Another advantage of the caravela latina was that it did not need a large crew. This was an important factor in voyages of exploration when scurvy, accidents, and violent encounters over one or two years might significantly reduce the number of personnel available to the expedition. Caravels were not just built in shipyards in Europe but also in colonies like Portuguese Goa.

One of the drawbacks of the caravel was that it could not carry as much cargo as other types of vessels like the carrack. This limited capacity was a serious disadvantage when, for example, the Portuguese gained access to the spice trade in Asia and wished to transport precious cargoes to Europe via maritime routes. For these trade routes, the much larger carrack ship was used, which could weigh up to 2,000 tons.

To counter the disadvantage of limited cargo space, the caravel design was tweaked to create the round caravel or caravela redonda. This type was larger and wider than a normal caravel and could weigh up to 300 tons. The round caravel usually had square-rigged masts for greater speed and a bowsprit with spritsail. A third variant was a four-masted caravel designed for use as a warship. Typically, three masts carried lateen sails and one was square-rigged. In many ways, this type of caravel was a forerunner of the 16th-century war galleon. Indeed, the development of the larger class of caravel was also a response to the increasing number of attacks on Portuguese vessels by the Dutch from the 16th century onwards. The larger vessel could carry more cannons.

The Portuguese Empire

In the 15th century, the Portuguese were keen to explore the coast of West Africa and perhaps access trade networks within the interior of that continent and so bypass the North African traders. The first major obstacle to this plan was a geographical one: how to sail around Cape Bojador and be able to make it back to Europe against the prevailing north winds and unfavourable currents? After 12 years of repeated failures to round the cape, the answer was a better ship design, that is, the caravel with lateen sails. By setting a bold course away from the African coastline and using winds, currents, and high-pressure areas, the Portuguese found they could safely sail back home. The treacherous Cape Bojador was thus navigated in 1434.

With ships like the caravel, the Portuguese Crown was now able to trade with and attack West African settlements in its search for gold, slaves and other valuable commodities. Caravels permitted the Portuguese to colonize three uninhabited archipelagoes: Madeira (1420), the Azores (1439), and Cape Verde (1462) in the Atlantic off the coast of West Africa. Using these islands as stepping stones, mariners began to explore ever-further southwards and beyond the Atlantic to other seas. In 1488 Bartolomeu Dias (c. 1450-1500) sailed down the coast of West Africa with a fleet of two caravels and a storeship, perhaps a caravela redonda. Dias made the first recorded voyage around the Cape of Good Hope, the southern tip of the African continent (now South Africa).

Famous Caravels

Although caravels were designed for coastal work, they could more than hold their own on longer sea voyages that spent many weeks away from land. A famous caravel used in this way was the Matthew of John Cabot (aka Giovanni Caboto, c. 1450 - c. 1498 CE), the Italian explorer who famously visited the eastern coast of Canada in 1497 CE and 1498 CE. Cabot was sponsored by Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509 CE) to search for a sea route to Asia, and although Cabot 'discovered' what the Italian called 'Newe Founde Launde’, he did not achieve his principal objective. The three-masted Matthew was 24 metres (78 ft.) long and weighed 50 tons. The ship had already enjoyed a long career in maritime trade and would do so after Cabot had finished with it.

Two famous round caravels were the Niña (‘The Girl’) and Pinta (‘The Painted One’), part of the fleet of Christopher Columbus (1451-1506 CE) which sailed to the New World in 1492. Each of these caravels had a crew of around 20. The Niña was rigged with square and lateen sails which made it the fastest ship of the trio commanded by Columbus.

Another notable caravel was the Berrio which was part of the small fleet Vasco da Gama (c. 1469-1524) sailed around the Cape of Good Hope and on to India between 1497 and 1499. Da Gama’s expedition was the first to find a direct sea route from Europe to Asia.

Representations of Caravels

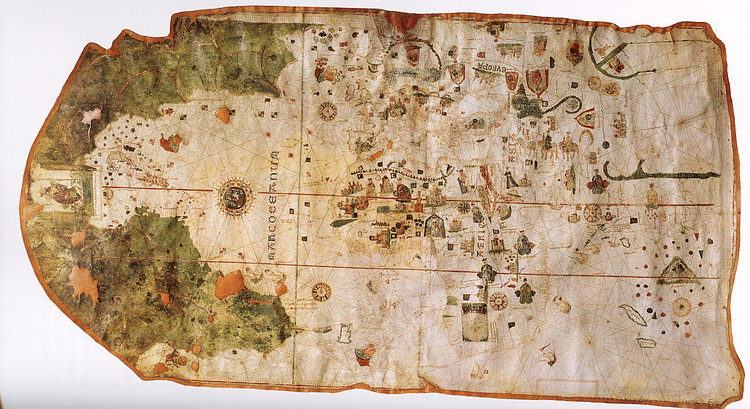

Caravels and carracks appeared in all manner of places besides on the sea. These ships were such an important part of maritime culture and empires that they appeared in countless paintings, as illustrations in books, as part of beautifully illustrated manuscripts, and on coats of arms. Caravels even appear in non-European art such as on Japanese screens produced in Portuguese Nagasaki. Perhaps the most famous book, packed full of depictions of caravels and other vessels of the period sorted by expedition fleets, is the mid-16th century Livro das Armadas now in the Academy of Sciences in Lisbon. Another interesting catalogue of ships is the 1616 Livro das Traças de Carpinteria which is, in effect, a construction manual and so shows illustrations of specific parts of ships in detail.

Caravels and carracks feature prominently in 16th- and 17th-century maps. For example, the celebrated giant map of the world drawn by Juan de la Cosa (c. 1450-1510) in 1500 shows caravels off the coast of Africa and rounding the Cape of Good Hope. The map is now in the National Naval Museum of Madrid, and its depiction of caravels emphasises how important this type of vessel was in gathering together ever-more geographical knowledge of the world during the Age of Exploration.