The armies of Carthage permitted the city to forge the most powerful empire in the western Mediterranean from the 6th to 3rd centuries BCE. Although by tradition a seafaring nation with a powerful navy, Carthage, by necessity, had to employ a land army to further their territorial claims and match their enemies. Adopting the weapons and tactics of the Hellenistic kingdoms, Carthage similarly employed mercenary armies from their allies and subject city-states. Military successes came in Africa, Sicily, Spain, and Italy, where armies were led by such celebrated commanders as Hamilcar Barca and Hannibal. Carthage's military dominance was, though, eventually challenged and bested by the rise of Rome and, following defeat in the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), Carthage's days as a regional powerhouse were over.

The Carthaginian Empire

Carthage was founded in the 9th century BCE by settlers from the Phoenician city of Tyre, but within a century the city would go on to found colonies of its own. An empire was created which covered North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily, and other islands of the Mediterranean. The new territory would be a source of vast wealth and manpower. Conversely, this would also bring Carthage into direct competition not only with local tribes but also contemporary powers, notably the Greek potentates and later Rome. In turn, this created a necessity for large military forces, especially land armies.

Commanders

The commander of a Carthaginian army in the field (rab mahanet) was selected for the duration of a specific war, usually from the ruling family. The general may often have had complete autonomy of action or, on other occasions, had to rely on the council of 104 and the two most important political persons at Carthage, the two suffetes (magistrates), for such important decisions as when to hold a truce, sue for peace, or withdraw. In addition, after a battle or war, the commanders would be subject to a tribunal which investigated their competence or otherwise. Different family groups within Carthage had their own private armies, which could then be employed for the state; a situation which caused intense rivalry between commanders. In addition, command was sometimes shared between two, or even three, generals, creating more opportunities for fierce competition.

Motivation must have been high as those generals who failed in wartime were treated harshly. One of the lesser punishments was a large fine whilst the worst case scenario was crucifixion. Several commanders, following defeat, committed suicide to avoid the latter penalty, although, this did not stop the council of 104 crucifying the corpse of one Mago c. 344 BCE. A serious consequence to the fear of failure inherent in the army command structure may have been that generals tended to be over-cautious and conservative in battle.

Organisation

The army of Carthage itself was composed of heavily armoured infantry drawn from the citizenry. This was an elite group of 2,500-3,000 infantry soldiers identified by their white shields and known as the Sacred Band. The name is copied from the elite army of Greek Thebes and indicates a general move away from Near Eastern practices to a Hellenization of the Carthaginian military from the 4th century BCE. The Sacred Band was barracked within the massive fortification walls of Carthage. A second source of troops was the allied cities and the conquered territory of North Africa, especially ancient Libya and Tunisia. These would have been led by Carthaginian officers and were paid for their service.

As neither of the previous two groups were very numerous or enjoyed a particularly glorious reputation in battle – after all, the Carthaginians were noted for their navy – a third group of professional mercenaries was relied upon to create an army which could match the enemies of Carthage. These came from all Carthage's allied and conquered states around the Mediterranean, especially Greece, Iberia, Gaul, and southern Italy. Another notable component of a Carthaginian army in the field was the highly skilled Numidian cavalry whose riders armed themselves with a javelin and rode without a bridle, such was their skill in controlling their mount. They carried a small shield for protection and also threw long poisoned darts at the enemy. An unusual contingent of mercenaries came from Libyan-Egyptian lands which fielded women in battle, usually riding chariots or horses. They carried crescent-shaped pelta shields and wielded double axes.

All of these groups of mercenaries remained a permanent fixture of the Carthaginian standing army from the end of the 3rd century BCE. To avoid the threat that successful mercenary armies took it into their heads to depose the ruling elite of Carthage and take the city's wealth for themselves the Carthaginians made sure that all senior and middle command positions were held by citizens of Carthage. Nevertheless, despite this precaution, in several instances mercenary armies would prove to be disloyal and even cause in-fighting between the rival clans of Carthage's aristocracy, most famously during the Truceless War (aka Mercenary War, 241-237 BCE).

Weapons & Armour

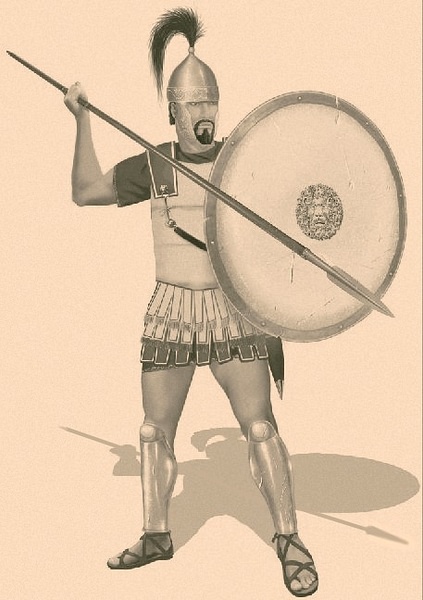

As the armies of Carthage were usually composite groups of Punic, African, and foreign mercenary forces their weapons and armour differed depending on the unit's origin or preferences. In addition, the Carthaginians were not averse to equipping themselves with the arms and armour of their fallen enemies. Contact with Greek forces in Magna Graecia and Sicily resulted in the Carthaginians themselves adopting such quintessentially Greek paraphernalia as the crested bronze Corinthian and Thracian helmets and heavy hoplite armour (a metal or leather tunic and greaves to protect the lower legs). Older style conical helmets were worn, as were helmets with face masks and metal breastplates covered in leather copied from Cypriot armour. The strengthened linen cuirass (linothorax) studded with bronze bosses and with hanging strips (pteryges) to protect the groin were also copied from Greek warriors.

Shields were circular (around 90 cm in diameter) or oval with a central vertical rib (the thyreos-type), although Celtic troops, for example, had a narrow rectangular shield of oak. Shields were decorated with motifs related to Punic religion, classic motifs such as Medusa, the Evil eye, or even personalised – Hasdrubal Barca had his own portrait on his silver shield. The Carthaginians seemed to have dressed up for battle with plenty of gold jewellery and animal skins being worn, especially by officers. Carthaginian officers would have further stood out in the heat of battle due to their impressive helmet plumes and glinting precious-metal armour. Generals often had expensive scale armour, such as that worn by Hannibal made from gilded bronze scales and inherited from his father.

The typical weapon was the sword, either with a straight blade or a curved single-edged one, the kopis of the Near East, with a dagger as a backup. Celts famously used long slashing swords while Iberian infantry had distinctive curved swords. Spanish tribes also used a short sword with great effect; something which did not go unnoticed by the Romans who would later adopt a similar type themselves, the gladius hispaniensis.

Archers were used, especially the skilled Moors and Cretans, but much less than in other armies. Bowmen were chiefly employed in chariots or on elephants to fire down on opposing infantry. Other weapons used were spears (3-6 m in length), short javelins (the principal cavalry weapon) and double-headed axes (bipennis). Slings were used to fire lead or stone bullets which were almond-shaped for maximum penetration into armour. They were especially used by the deadly mercenary slingers from the Balearic Islands.

Artillery was a component of Carthaginian armies in Sicily where the cities were well-fortified. The Carthaginians were quick to copy the Hellenistic inventions of catapult (for stones and incendiaries) and crossbows. During a siege, they also employed battering rams, mobile siege towers, mounds, and mining to overcome enemy fortifications. We know that Carthage itself was equipped with artillery machines for defence.

Chariots

The Carthaginians employed war chariots up to the 3rd century BCE. These were constructed from wooden frames covered with panels of woven willow branches. They were single-axle chariots and could carry two men: a driver and an archer. Sometimes a third man, a hoplite, would join them. The wheels could be fitted with blades, and the team of two or four horses was protected with metal breastplates and ox-hide side covers. Like cavalry, they were used to break up the enemy infantry lines. Needing flat terrain to operate effectively they were largely restricted to use in North Africa and southern Spain and went completely out of use from the 3rd century BCE.

War Elephants

The Carthaginians used in warfare a now extinct variety of elephant once native to North Africa. Although, Hannibal may have had some larger Indian elephants via his ally Ptolemy II of Egypt. Tusked and reaching a height of 2.5 metres, the elephants were made even more fearsome by adding armour to the head, trunk, and sides and blades or spears to the tusks. Controlled by their driver (mahout) they were used to disrupt enemy formations. Not large enough to carry a superstructure (howdah), this variety of elephant may have permitted a second rider armed with a bow or javelins. Before battles, elephants would be given fermented wine to make them behave more erratically and increase their trumpeting and stamping. No doubt the appearance and noise of elephants caused panic amongst the enemy's men and horses, but they were wildly unpredictable in battle and could cause as much damage to their own side as the opposition. When enemy forces became used to them and trained their horses not to panic, or if the terrain was unsuitable, then their effectiveness was greatly reduced.

Strategies & Tactics

After an initial round of skirmishes involving light cavalry, the Carthaginian army attacked the enemy head-on with heavy infantry, much like the Greeks had been doing for centuries with the phalanx (a line of tightly grouped hoplites protecting each other with their shields). Following the successful Macedonian model of a speared phalanx, the Carthaginian army was similarly organised into companies of around 250 men organised into 16 lines of 16 troops, which then collectively formed battalions of around 4,000 men. Light infantry was stationed on the wings and protected the flanks of the phalanx which might draw in the enemy lines. Troops were coordinated during battle using standards which, for Carthaginian units, were staffs with ribbons topped by the familiar Punic crescent moon and sun disc symbol. Each ethnic group would have had their own standards such as the Celtic wild boar image and shield blazons were also used to identify who was who.

The elephant corps was used in front of the infantry to disrupt the opposition ranks and light cavalry units to harass the enemy from the wings or rear. There was also a small unit of heavy cavalry, composed of Carthaginian citizens only, which could break up the enemy's infantry lines mid-battle. Cavalry was also used to harass the enemy when in retreat. When not involved in head-to-head battles, the cavalry, especially the mobile and highly manoeuvrable Numidian corps, were used to ambush enemy troops or lead them into ambush by infantry troops.

In some battles, the Carthaginian army numbered up to 70,000 men (but more often less than half that figure) and its success was very much down to the commander's ability to galvanise all of the disparate groups into a cohesive fighting force. Hannibal was particularly renowned for his ability in this area and in his willingness to adapt superior enemy tactics and formations such as after the Battle of Lake Trasimene (217 BCE) when he likely adapted the more flexible Roman maniple troop deployment as opposed to the more static phalanx.

Conclusion

In some theatres the Carthaginian army enjoyed great successes, notably in North Africa, Sicily, Spain, and Italy where Hannibal famously won four great battles against Rome. However, the Second Punic War was perhaps a turning point. The Roman general Scipio Africanus managed to persuade the Numidian cavalry to join his cause and defeated Hannibal and his elephants at the Battle of Zama (202 BCE). Rome, with its standardised, well-equipped and well-drilled armies, which could be replaced from a seemingly never-ending supply of manpower and wealth, had taken ancient warfare to a new level of professionalism. The inherent weaknesses in the Carthaginian army - disparate groups of sometimes disloyal mercenaries, confused command structures, and an over-reliance on heavy infantry and war elephants - meant that Carthage was, ultimately, unable to maintain its position as a Mediterranean superpower and keep pace with mighty Rome.