Carthaginian warfare has been overshadowed by defeat to Rome in the Punic Wars, but for six centuries before that Carthage was remarkably successful in conquering lucrative territories in North Africa, the Iberian Peninsula, and Sicily. By combining the finest mercenary armies with their own elite forces and huge naval fleet, Carthage was able to dominate the western Mediterranean and protect and expand its vast network of colonies and trading posts from the 9th to 3rd centuries BCE.

Purpose of War

Carthage was founded by the Phoenician city of Tyre in 813 BCE as a handy location along western Mediterranean trade routes, and the colony would go on to prosper and found its own colonies, eventually taking over the old Phoenician network too. Such a large geographical spread of interests required a naval fleet to safeguard both the ships which plied their trade across the seas and the ports which gave them protection and access to lucrative hinterlands. In addition, a land army was sometimes required in order to defend Carthage's trading interests from local tribes and rival powers, especially the tyrants of Sicily and later Rome. Another, equally important role for armies was as an offensive means to expand the empire by taking control of new territories rich in natural resources such as the silver mines of Iberia.

Ceremonies of War

As with most other ancient cultures warfare for the Carthaginians was, like any other state activity, inseparable from religious beliefs. War could not be conducted without divine sanction. Accordingly, sacrifices were made to the Punic gods before key battles in order to ensure their favour and ultimate victory. Sometimes during a long conflict even new temples were built to such important deities as Tanit, Melqart, and Baal Hammon to please them and make sure their support did not waver. Animal entrails were read too prior to battles, where omens were established which reassured the troops with their promise of victory. In dire moments sacrifices were also made in a last ditch effort to avoid defeat. The most notorious example of this, recounted by the ancient historian Diodorus, was when Agathocles, the tyrant of Syracuse, invaded North Africa in 310 BCE. In response to this threat hundreds of noble children were sacrificed. So too, after the battle, victories were celebrated with more sacrifices and conquests were recorded on tablets and stelae set up at Punic temples.

Commanders

The commander of a Carthaginian army or naval force (rab mahanet) was selected for the duration of a specific war, usually from the ruling family. The general may often have had complete autonomy of action or, on other occasions, had to rely on the Carthaginian government for such important decisions as when to hold a truce, sue for peace, or withdraw. In addition, after a battle or war, the commanders were subjected to a tribunal which investigated their competence or otherwise. There was intense competition between commanders, not helped by the fact that command was sometimes shared between two, or even three, generals.

Motivation for commanders was high too as those generals who failed in wartime were treated harshly. One of the lesser punishments was a large fine whilst the worst case scenario was crucifixion. Several commanders, following defeat, committed suicide to avoid the latter penalty. A serious consequence of the fear of failure inherent in the army command structure may have been that generals tended to be overcautious and conservative in battle. This was in direct contrast to Roman commanders who had their command for one year, only leading to a more aggressive approach to warfare as they tried to win total victory before being removed from office.

The more successful commanders not only possessed the military skills to exploit the unique situations of individual battles and the weaknesses of their enemies but also the ability to mould their own mercenary fighting force into a homogenous unit. This was primarily achieved by a cult of personality. Hannibal, for example, went one step further than his father Hamilcar Barca (who had used such imagery on his coins) and identified himself as Hercules-Melqart, the figure who was a mix of the invincible Greek hero and the Phoenician-Punic god. This appealed to both Carthaginians and Greeks. It was a handy propaganda tool with Greek contingents in the Carthaginian army and when fighting in such places as Magna Graecia where the cult was as strong as anywhere. To bolster his divine claims Hannibal once recounted a dream he had had where Melqart specifically instructed him to invade Italy and even gave him a guide to get there in the most efficient way. All of these ploys helped to reassure the common soldier that they were fighting on the right side with the best general.

Soldiers & Weapons

The army of Carthage the city was composed of heavily armoured infantry drawn from the citizenry. This was an elite group of 2,500-3,000 infantry soldiers identified by their white shields and known as the Sacred Band. The bulk of the Carthaginian army which fought across the empire was, though, composed largely of mercenary units – both paid local allies (e.g. from Libya and Tunisia) and mercenary armies from Greece, Iberia, Southern Italy, and Gaul. One of the best corps in the Carthaginian army was the cavalry force of their allies, the Numidians. To avoid the threat that successful mercenary armies rebelled against the ruling elite of Carthage, the Carthaginians made sure that all senior and middle command positions were held by citizens of Carthage. Nevertheless, despite this precaution, in several instances mercenary armies would prove to be disloyal and even cause in-fighting between the rival clans of Carthage's aristocracy, most famously during the Truceless War (aka Mercenary War, 241-237 BCE).

As the armies of Carthage were usually composite groups of foreign mercenary forces; their weapons and armour differed depending on the unit's origin or preferences. In addition, the Carthaginians were not averse to equipping themselves with the arms and armour of their fallen enemies. The Greek hoplite was perhaps the most common model – heavy armour, large shield, spear, and sword. There were also contingents of slingers and archers. Up to the 3rd century BCE war chariots were used, but their limitation of requiring good terrain saw their eventual abandonment in favour of more mobile cavalry.

Artillery was a component of Carthaginian armies in Sicily where the cities were well-fortified. The Carthaginians were quick to copy the Hellenistic inventions of catapult (for stones and incendiaries) and crossbows. During a siege, they also employed battering rams, mobile siege towers, mounds, and mining to overcome enemy fortifications. We know that Carthage itself was equipped with artillery machines for defence.

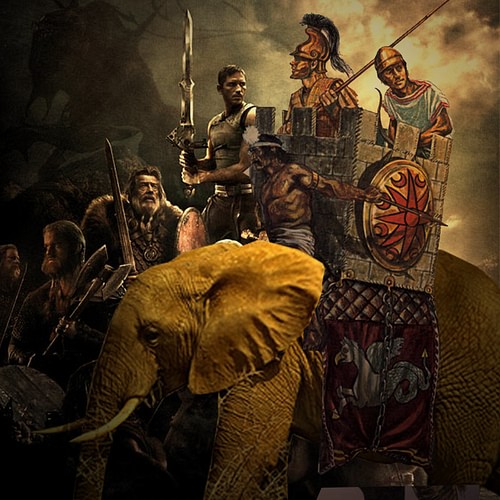

One of the most distinctive Carthaginian weapons was the war elephant. Tusked and reaching a height of 2.5 metres, the elephants were made even more fearsome by adding armour to the head, trunk, and sides, and blades or spears to the tusks. Controlled by their driver (mahout), they were used in front of the infantry lines to disrupt enemy formations and to harass the enemy from the wings or rear. Not large enough to carry a superstructure (howdah), the type of elephant used by Carthage may have permitted a second rider armed with a bow or javelins. No doubt the appearance and noise of elephants caused panic amongst the enemy's men and horses, but they were wildly unpredictable in battle and could cause as much damage to their own side as the opposition. When enemy forces became used to them and trained their horses not to panic or if the terrain was unsuitable, then their effectiveness was greatly reduced.

Strategies

In land battles, after an initial round of skirmishes involving light cavalry, the Carthaginian army attacked the enemy head-on with heavy infantry, much like the Greeks had been doing for centuries with the phalanx (a line of tightly grouped hoplites protecting each other with their shields). Hannibal, however, showed a willingness to adapt superior enemy tactics and formations such as after the Battle of Lake Trasimene (217 BCE) when he likely adapted the more flexible Roman maniple troop deployment as opposed to the more static phalanx.

Light infantry was stationed on the wings and protected the flanks of the phalanx which might draw in the enemy lines. Troops were coordinated during battle using standards. Each ethnic group would have had their own, such as the Celtic wild boar image, and shield blazons were also used to identify who was who. When not involved in head-to-head battles to break up formations and harass the enemy's flanks, the cavalry units were used to ambush enemy troops, lead them into ambush by infantry troops, or in guerrilla tactics to constantly harass enemy armies and their logistical support.

Naval Warfare

The size of the Carthaginian fleet changed depending on the period, but according to the ancient historian Polybius, Carthage had a fleet of 350 ships in 256 BCE. Such were the requirements of Carthage's large navy that ships were constructed using mass-produced pieces marked with numbers for ease of assembly.

The naval fleet of Carthage was composed of large warships propelled by sail and oars which were used to ram enemy vessels using a bronze ram mounted on the prow below the waterline. The ships were the trireme with three banks of rowers, the quadrireme, and quinquereme. The quinquereme, so called for its arrangement of five rowers per vertical line of three oars (a total of 300 rowers), became the most widely used in the Punic fleet. Catapults could be mounted on the deck of these large vessels but were probably limited to siege warfare and not used in ship-to-ship battles.

Attempts to ram enemy ships could be made in two ways. The first, the diekplous or breakthrough, was when ships formed a single line and sailed right through the enemy lines at a selected weak point. The defending ships would try not to create any gaps in their formation and perhaps stagger their lines to counter the diekplous. The second tactic, known as periplous, was to try and sail down the flanks of the enemy formation and attack from the sides and rear. This strategy could be countered by spreading one's ships as wide as possible but not too much so as to allow a diekplous attack. Positioning a fleet with one flank protected by a shoreline could also help counter a periplous manoeuvre, especially from a more numerous enemy. While all this chaotic ramming was going on, smaller vessels were used to haul stricken ships away from the battle lines or even to tow away captured vessels. Oarsmen were expected to fight in landing operations and help build siege engines but not in ship-to-ship battles. The larger ships were decked and would have carried complements of armed men, both archers and marines armed with spears, javelins, and swords, who could board enemy vessels given the opportunity.

Aside from naval battles, the Carthaginian fleet was also vital for transporting armies, resupplying them by providing an escort for transport ships, coastal raids, attacking enemy supply ships, blockading enemy ports, and relieving Carthaginian forces when they were themselves besieged.

Victor's Spoils & Reprisals

The rewards of military victory for Carthage were control of new territories with their natural resources, acquisition of slaves, sometimes the incorporation of parts of the defeated army into their own, and the state treasuries and granaries of conquered cities. As Carthage employed mercenaries, one of the first priorities after a victory was to pay them, and this was done with coinage or by allowing the soldiers to take any booty they could get their hands on from the defeated – weapons, armour, jewellery, foodstuffs, and so on.

Carthage earned a bloody reputation for its treatment of the vanquished, but this should be tempered with the fact that most of the sources are pro-Roman. We know, for example, that Hannibal released non-Roman enemy troops on several occasions to increase the chances of local areas revolting against Rome. Similarly, some were promised the return of their land which had been taken from them by the Romans. Certainly, though, sometimes war prisoners were sacrificed to honour the Punic gods and give thanks for victory. There are also tales of prisoners being executed en masse, sometimes imaginatively as in one case where elephants were used to trample the unarmed captives. Defeated leaders could expect no better and were often cruelly executed. One Hasdrubal is known to have crucified the Iberian prince Tagua, a Celtic leader named Indortes was blinded before he was crucified, and the Roman general Regulus was put inside a barrel lined with spikes and then rolled through the streets of Carthage.

This brutality did sometimes serve a political purpose for canny generals could then seem especially generous when they treated the defeated well, they could encourage enemy cities to capitulate without much bloodshed and avoid the same fate and, perhaps not least, persuade their own troops of what they could expect in retaliation themselves from the enemy if they were captured, and so they became even more motivated to fight well.

Famous Victories

In some theatres the Carthaginian army enjoyed great successes, notably in North Africa, Sicily, and Spain. An important victory came near Tunis during the First Punic War (264 - 241 BCE) with Rome when the Carthaginians wisely employed the mercenary Spartan commander Xanthippus. In 255 BCE, he reorganised the army and brilliantly combined 100 war-elephants with 12,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry to totally defeat two legions and capture the Roman general Regulus in the process. 12,000 Romans were killed against 800 Carthaginians.

The great general Hamilcar Barca was particularly successful in Spain in the 230s BCE. He supplemented his original landing force of some 25,000 with local recruits and amassed a 50,000-strong army which included 100 elephants. Using a blend of terror and diplomacy, Hamilcar relentlessly expanded his control over southern Spain, and the riches from these campaigns were channelled back to Carthage to make it the wealthiest city in the ancient world.

Perhaps the finest hour of Carthage's army was Hannibal's streak of four great battles against Rome in Italy during the Second Punic War (218 - 201 BCE). His victories at the Ticinus (Ticino) River near Pavia and the Trebia River in December 218 BCE, Lake Trasimene in June 217 BCE, and at Cannae in Apulia in August 216 BCE rocked the Roman world. Masterfully blending his mixed mercenary army into a coherent and disciplined whole, taking full advantage of local terrain, and employing his troops in fast battlefield manoeuvres, Hannibal, for a while at least, was invincible.

Infamous Losses

Perhaps Carthage's most shocking naval loss was their very first sea engagement with Rome at the battle of Mylae (Milazzo) in 260 BCE. The Roman fleet of 145 ships defeated the Carthaginian fleet of 130 ships which had not even bothered to form battle lines, so confident were they of victory against the untested Roman sailors. When the Carthaginian flagship was captured, the commander was forced to ignominiously flee in a rowing boat.

In 202 BCE, the Roman general Scipio Africanus famously defeated the great Hannibal and his elephants at the Battle of Zama in western Tunisia. Scipio managed to persuade the Numidian cavalry to join his cause and he brilliantly arranged his infantry to form corridors which allowed Hannibal's 80 elephants to harmlessly charge through, then sent them back to cause havoc with the Carthaginian lines. It was the battle which would end the Second Punic War and, effectively, Carthage's position as a major power.

Carthage's greatest loss was nothing less than total destruction at the hands of the Romans in the Third Punic War (149-146 BCE). After a lengthy siege and staunch resistance, the city finally fell to the siege engines of Scipio Africanus the Younger. Buildings were destroyed, the people were sold into slavery, and the land officially cursed.

Conclusion

Carthage was, then, an accomplished practitioner of warfare for centuries but eventually, and despite a heroic effort which several times almost brought victory, more than met its match in Rome with its professional and well-trained army backed by a seemingly endless pool of replacements and financial support. The inherent weaknesses in the Carthaginian army - disparate groups of sometimes disloyal mercenaries, confused command structures, and an over-reliance on heavy infantry and war elephants - meant that Carthage was, ultimately, unable to maintain its position as a Mediterranean superpower and keep pace with mighty Rome.