Carthago Nova (modern-day Cartagena) was a city on the southern Iberian Peninsula, Spain, originally known as Mastia. Human habitation of the region predates the Neolithic Period, but the area around the site of Carthago Nova seems to have been sparsely populated until after the Bronze Age when a port city was built on a peninsula jutting into the Mediterranean Sea.

The 4th-century CE Latin poet Rufus Festus Avienus identified Mastia with Massia of the Tartessians but that city was located in the region of the Tartessian Confederation around the ancient city of Carteia (near Gades, modern-day Cadiz), although the Tartessians almost certainly traded with Mastia and, according to some scholars, were the original inhabitants of the region.

The city was founded as Qart Hadasht (“Carthage”) by the Carthaginian general and politician Hasdrubal the Fair (l. c. 270-221 BCE) in 228 BCE. It was taken by the Roman general Scipio Africanus (l. 236-183 BCE) in 209 BCE during the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) and renamed Carthago Nova (“New Carthage” but, literally, “New New City” since “Carthage” itself means “New City”).

Carthago Nova would continue to play an important part in Rome's economy, both as a trade center and supplier of silver and various commodities, throughout its history. It was later taken by the Vandals and then the Visigoths before being conquered in the 7th century CE during the Muslim invasion. Afterwards, it was held by various Muslim caliphates until the Reconquista of the 13th century CE during which Christian armies retook Spanish territories from the Muslims.

The First Punic War

The city of Mastia was a known trade center of the Phoenicians (who may have founded it) and who traded with the Tartessians, well-known for their production of silver. Scholar B. H. Warmington, following earlier scholars, identifies Tartessos (in the region around Cadiz) with Tarshish from the Bible (Genesis 10:4, I Chronicles 1:7, Ezekiel 27:12, among others) and points out how similar the coastline around Cadiz is to that of ancient Mastia, thus explaining how ancient authors may have confused the two (though the site of biblical Tarshish has not been agreed on by any scholarly consensus). It has also been established that Mastia and Carteia were both known for their silver mines, wealth of resources, and their engagement in maritime trade.

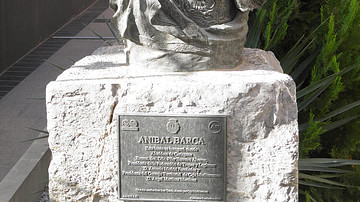

Almost nothing is known of the specifics of early Mastia, but it would become one of the many cities of the Iberian Peninsula to be caught up in the Punic Wars (264-146 BCE) between the cities of Carthage of North Africa and Rome in Italy. The First Punic War (264-241 BCE) began over control of Sicily which both cities claimed. Carthage, at this time, was the greatest power in the Mediterranean while Rome was still a relatively small city with no navy. Carthage sent their general Hamilcar Barca (l. 275-228 BCE) against the Romans, and he might have been victorious if his city had better supported him. As it was, Rome was victorious and demanded reparations as part of the treaty ending the conflict.

Hamilcar and his son Hannibal (l. 247-183 BCE), along with his son-in-law Hasdrubal the Fair, went to Iberia allegedly to take the Iberian silver mines in order to pay Carthage's debt to Rome but, actually, to colonize the region and renew hostilities. In a series of military campaigns, Hamilcar conquered the various tribes of the region, amassing significant wealth while also adding to his army through conquered conscripts. When he was killed in battle in 228 BCE, Hannibal was still too young to succeed him and so command went to Hasdrubal the Fair.

Hasdrubal founded his city of Qart Hadasht in Mastia in 228 BCE and chose to focus on diplomatic missions rather than continuing the military campaigns of his father-in-law. Qart Hadasht became the seat of power for Carthaginian Iberia from which Hasdrubal administered the cities and regions conquered by Hamilcar while adding to his territory through negotiations, alliances, and treaties. His success in expansion and able government upset the city of Massilia and its colonies, north of the Ebro River, who were friends of Rome. The Massilians appealed to Rome who then sent an embassy to Qart Hadasht in 226 BCE to curtail any further Carthaginian conquests in Iberia.

Hasdrubal agreed to a treaty which included the stipulation that he would not cross north of the Ebro River under arms. Any territories south of the Ebro, it seems to have been understood, were fair game for Carthage. Hasdrubal was a skilled diplomat and could have perhaps prevented the Second Punic War but was assassinated by a palace servant seeking to avenge his master who had been killed by the Carthaginians. After Hasdrubal's death, the troops unanimously called for Hannibal to assume command of the forces in Hispania.

The Second Punic War

Hannibal Barca was a shrewd tactician who had grown up on the battlefield under the tutelage of his father and, further, had sworn to never be a friend to Rome. Any diplomatic means of preventing conflict with Rome died with Hasdrubal since Hannibal was far from likely to make any concessions further than the agreement already signed. Problems began when the city of Saguntum, a friend of Rome (that is, under Roman protection), expelled Carthaginian loyalists in 221 BCE and installed a Roman administration with Rome's approval. Rome then sent word to Qart Hadasht that Hannibal was not to move against Saguntum. B. H. Warmington comments on the situation:

It is not known whether Rome's friendship with Saguntum dated from before or after the Ebro agreement; in either case, it introduced an awkward element into the situation because it was inevitable that the Carthaginians would claim a free hand south of the river even if this was not specified in the agreement; if you agree not to go beyond a point, you presumably expect freedom of action up to it. If it [Rome's friendship with Saguntum] came before the Ebro treaty, Carthage could justifiably consider that it was annulled by the implications of the treaty; if it came after, the Romans could be held guilty of most provocative action [by installing a pro-Rome government in a formerly Carthaginian city]. (194)

Hannibal interpreted their actions according to the latter, charged Rome with breaking the peace, and marched on Saguntum in 218 BCE, initiating the Second Punic War. He sacked the city as a warning to any other pro-Roman communities and then, without waiting for Rome to arrive and then wasting time and resources on engagements in Iberia, he placed his younger brother Hasdrubal Barca (l. c. 244-207 BCE) in charge of the Iberian forces and took the fight to Rome by leading his army across the Alps into Italy.

Rome sent word to Carthage demanding that they surrender Hannibal to them, unaware that Carthage had already given Hannibal free hand in dealing with the Romans or that he was marching toward their city. Rome had, meanwhile, already sent forces to Iberia to deal with the Carthaginian army – which they thought was still under the command of Hannibal. Carthage, of course, refused to surrender Hannibal, and the Roman embassy returned, no doubt thinking that Hannibal would simply be defeated in Iberia.

They would find they were wrong on a number of fronts: Hannibal was in Italy and Hasdrubal proved himself an able commander and defeated the formidable Roman generals sent against him. Even so, his string of victories or holding actions ended with the arrival of the general Scipio Africanus in 211 BCE.

Rome & Carthago Nova

Scipio won every engagement as he marched toward Qart Hadasht to lay siege to the city. At Tarraco, he learned that there was a lagoon (or marsh) on one side of the city whose water level dropped at a certain time. One might take the city from this side by wading through the shallow waters when the tide went out. This report of the events comes largely from the historian Polybius (l. c. 208 - c. 125 BCE) although others (Livy and Appian) also treat of the subject. The traditional story is that Scipio staged a distraction at the gates by launching one part of his forces against it while he sent another segment of troops through the lagoon at low tide to take the city.

Scholar Benedict J. Lowe, however, points out that it is more likely the “lagoon” was a salt marsh which was utilized by the city to harvest salt from the sea. The water level would be adjusted by sluices. Seawater would enter the marsh, the water level would slowly be decreased, and the salt residue left on trays would provide the city with an important and valuable resource. Lowe claims, cogently, that it is far more likely that, at Tarraco, Scipio learned of this salt marsh and the sluices and so carefully orchestrated his attack so that the defenders would be focused on the city's gate while 500 of his men went around, opened the sluices to drop the water level, and then waded across the undefended marsh to attack the city unaware, rather than relying on the course of the tides.

Qart Hadasht fell to Scipio, who then renamed it Carthago Nova. Hasdrubal's winning streak was over and, at Baecula in 208 BCE, he was defeated. Before he could be captured or killed, he escaped over the Alps to join his brother in Italy. Hasdrubal would die in battle only a few months later in 207 BCE, and Hannibal would be defeated by Scipio Africanus at the Battle of Zama in 202 BCE, ending the Second Punic War.

Carthago Nova Under Rome

The city flourished under Rome as a vital port in trade from which Iberian resources made their way to Italy. Among the many commodities Rome came to rely on were salt, silver, fish, esparto grass, and grain. Esparto grass was used in rope-making and basket weaving while some of the fish were used to produce the popular condiment known as garum. As the city became more and more prominent, it was known to traders by various names: Carthago Argentaria (Carthage of Silver), Carthago Skombraria (Carthage of Salted Fish), and Carthago Spartaria (Cartage of Esparto Grass). The city expanded during this time (c. 202-44 BCE) as it was perfectly situated for trade but also one of the safest places one could live owing to its position on the coast. Polybius describes the city c. 133 BCE:

New Carthage lies halfway down the coast of Spain in a gulf which faces south-west [and] this gulf serves as a harbor for the following reason. At its mouth lies an island which leaves only a narrow passage on either side and, as this breaks the waves of the sea, the whole gulf is perfectly calm, except that the south-west wind sometimes blows in through both the channels and raises some sea. No other wind, however, disturbs it as it is quite landlocked. In the innermost nook of the gulf a hill in the form of a peninsula juts out, and on this stands the city, surrounded by the sea on the east and south and on the west by a lagoon which extends so far to the north that the remaining space, reaching as far as the sea on the other side, [connects] the sea with the mainland. (Miles, 224)

The city was made a colony under Julius Caesar and the inhabitants given full rights under Roman law in 44 BCE in gratitude for its support of Caesar in his war with Pompey the Great. Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) lavished funds on the city, redesigning it and ordering the construction of new streets, a theater, a forum, monuments, and the Augusteum, part temple and part college. Silver mined from the Sierra Minera helped pay the Roman army while lead was used for, among other things, the pipes which brought water along the aqueducts from outlying reservoirs into the city of Rome.

As Rome went through its turmoil of the Crisis of the Third Century (235-284 CE), Carthago Nova suffered along with most of Rome's other colonies. The eastern part of the city was practically abandoned as resources dwindled and people moved to the western side, most likely to conserve whatever assets they had. Silver mining was disrupted, possibly due to lack of labor, and other natural resources overused. In 298 CE, the emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE), credited with ending the Crisis of the Third Century, attempted to revive the region by creating the province of Hispania Carthaginensis with Carthago Nova as its capital, and while this did do some good, Rome itself was in decline and could do little to help restore the city to its former glory.

Conclusion

The Vandals took the city in 409 CE, lost it to the Visigoths in 425 CE, and sacked it in 435 CE. Afterwards, the Visigoths reclaimed the city and held it until it was taken by the Byzantine Empire in c. 540 CE who made the city the capital of their westernmost province, Spania. In the early 8th century CE (probably c. 714 CE) the Byzantines surrendered the city during the Muslim invasion of Spain. The various caliphates who held the city valued it just as highly as Rome had previously and restored the city which had fallen into decay under the Visigoths. The Muslim Moors renamed Carthago Nova Qartayannat al-Halfa (also given as Cartajana Emirate), repaired the streets, renovated the buildings and port, and built a grand mosque in the center of town. In time, “Cartajana” evolved into the modern name of the city, “Cartagena”.

Between c. 711-1492 CE, the Christian monarchs initiated an aggressive policy of reclaiming Spanish territories from the Moors, known as the Reconquista. In 1243 CE, Ferdinand III of Castille (r. 1217-1252 CE) took Cartajana with the rest of the region of Murcia. His successor, King Alfonso X of Castille (r. 1252-1284 CE), restored the city and granted it license over its own resources, encouraging financial growth and stability which attracted religious orders such as the Augustinian monks who initiated the construction of a cathedral in the city (possibly the Cathedral of Santa Maria la Vieja later destroyed during the Spanish Civil War in 1939 CE) as well as other buildings.

Cartagena became a religious center for the Augustinians and later the Franciscan Order and reclaimed its status as a significant port of trade but declined during the Age of Discovery (15th-17th centuries CE). During this period, European nations were concentrating on acquiring land and resources in the so-called New World and establishing ports there, and so favored Spanish ports closer to North America (Cadiz and Seville) while Cartagena was forgotten.

The city revived toward the end of the 17th century CE, however, and has continued to prosper, more or less depending on circumstances, since that time. Today it is a popular tourist site and, although most of ancient Carthago Nova remains buried under the modern city, excavations have uncovered some of the most significant structures (the Augusteum and the theatre, among others). These, and the museum with its interactive displays, now help to tell the story in the present day of the once-great city.