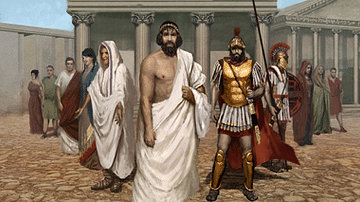

Cassander (c. 355-297 BCE, r. 305-297 BCE) was self-proclaimed king of Macedon during the political turmoil following Alexander's death. Born in Greece as the son of Antipater, the regent of Macedon and Greece in the absence of Alexander the Great, he ruled beside his father eventually battling against the commander Polyperchon for supremacy in Greece. His alliance with Seleucus I Nicator and Ptolemy I against Antigonus I brought him into the Wars of the Diadochi, the battle over the remnants of Alexander's domain. His murder of Alexander's mother and son ended any hope for an heir to the king's empire. Cassander's death in 297 BCE would, for a time, bring stability, but without an heir, his beloved Macedon would fall into the hands of others.

Early Life

Throughout his campaign against the Persians, Alexander the Great remained aware of the many troubles plaguing his homeland of Macedon. Although the regent Antipater was able to suppress a rebellion staged by Agis II of Sparta, he was unable to prevent Alexander's mother, Olympias, from constantly complaining to his son about the regent's supposed abuse of power. She despised Antipater, and he referred to her as a "sharp-tongued shrew." Finally, Alexander opted to listen to his mother and summon Antipater to Babylon. Believing it to be a death sentence, he chose instead to send his son Cassander. Alexander was not pleased, and the conflict that ensued may have brought about the king's early death.

Cassander and Alexander were not strangers; however, it became obvious many years later that they were not close friends. They were both about the same age and, along with Ptolemy and Hephaestion, students of the great Athenian philosopher Aristotle. Now, the year was 323 BCE, and as Cassander stood before his king intending to make a valiant plea on his father's behalf, he witnessed several Persians prostrating themselves before Alexander - an old Persian custom called proskynesis. His immediate reaction was to laugh. The historian Plutarch in his Greek Lives wrote, "… he could not stop himself laughing, because he had been brought up in the Greek manner and had never seen anything like that before." Alexander grew irate and "grabbed hold of Cassander's hair violently with both hands and pounded his head against the wall" (378). The image of this brutal attack would remain with Cassander for years to come and whenever he would see a statue or painting of the king, he would faint. Plutarch wrote of this malady,

… when he was king of Macedonia and master of Greece, he was walking around Delphi looking at the statues, when he suddenly glimpsed a statue of Alexander and became so terrified that his body shuddered and trembled, he nearly fainted at the sight and it took a long time for him to recover. (379)

Alexander's Death

On June 10, 323 BCE Alexander the Great died. Since that time, arguments and rumors have persisted concerning the possible cause - malaria, an old wound, his alcoholism, or even poisoning. This latter cause was something Olympias wholeheartedly believed. However, the rumor of poisoning, regardless of any direct evidence, brought into the conversation the names of Cassander, his brother Iolaus, Antipater, and even Aristotle. Supposedly, according to rumor, Aristotle, on the orders of Antipater, obtained the poison from a spring that flowed into the River Styx; Cassander carried it to Babylon in the hoof of a mule; and it was delivered to the king by Iolaus, Alexander's cupbearer. Plutarch did not give credence to the poison rumor. Later, Antipater made every attempt to defend himself against the rumors in order to win the hearts of the Greek people.

After Alexander's death, the empire he had so fearlessly built fell into chaos. And, while the commander Perdiccas possessed both the king's signet ring and body - the commander Ptolemy would later kidnap the body - no one had been named as either the successor or heir; however, it was accepted that Alexander's child by Roxanne, the future Alexander IV, would one day rule. Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus, son of Philip II of Macedon and Philinna, was named Philip III and chosen to rule as co-regent until young Alexander was old enough to rule alone. Meanwhile, although there was no child to consider, Roxanne, to affirm her status as Alexander's only wife, poisoned Darius's daughter (and Alexander's wife) Stateira and threw her body into a well - she also killed the sister Drypetis for no apparent reason. Since the future Alexander IV was yet to come of age, the commanders resorted to arguing among themselves, concerned more with gaining regency over a portion of the empire than appointing a successor.

Wars of Succession

At a meeting held in Triparadeisus presided by Antipater in 321 BCE, the vast empire was divided among the various commanders. The more notable assignments confirmed in the agreement were: Ptolemy had Egypt, Seleucus Babylonia, Lysimachus had Thrace, while Antigonus ruled much of Asia Minor. Lastly, Antipater retained his regency over Macedonia and Greece. Alliances were made, and alliances were broken. Over the next three decades, the Wars of Succession brought nothing but chaos and confusion. In the end, Alexander IV, his mother, and even Olympias would be dead, and the once-great empire of Alexander would die with them.

Antipater and Cassander realized that their tenuous hold on Greece and Macedonia was not safe. With little recourse, they looked to the other commanders for support eventually forming an alliance with Antigonus the One-eyed. Antigonus has sought Antipater's help after he and Perdiccas argued - Antigonus had refused to help the Perdiccas' ally Eumenes in a fight to retain his territory. Eumenes had been declared an enemy of the state at Triparadeisus and condemned to death. However, Cassander wisely grew to be suspicious of the old commander's intentions. Antipater acknowledged his son's concern, and the two met with Antigonus. According to their agreement, Antigonus lost control of much of his veteran army; they were replaced by newer recruits. When Antipater and Cassander returned to Macedon, Antigonus gathered his forces and defeated Eumenes in 321 BCE. In the same year, Perdiccas would be defeated in a battle against Ptolemy and killed by his own men. Several years later, when Cassander gained control over Macedon and most of Greece, the cagey commander and old veteran would clash. For now, however, he stayed cautious.

Cassander As Chilarch

Cassander remained loyal to his father to the very end, but when Antipater died in 319 BCE, he failed to name his son as his heir. He felt Cassander too young and inexperienced to rule alone and defend against the other regents. Instead, Antipater named the capable commander Polyperchon. Cassander was named chilarch or second in command. Of course, the two would immediately clash. Something that may have influenced Antipater's decision comes from Cassander's childhood. He had always been a sickly child, and it was a Macedonian custom that a boy had to kill a wild boar without a net to gain the privilege of reclining at a table as an adult. Cassander never did and had to sit upright on his couch even as an adult. Despite his new role as chilarch, Cassander would not remain idle long and sought alliances elsewhere. Eventually, despite his misgivings, he looked across the Hellespont and allied himself with Antigonus.

Fearing this alliance, Polyperchon looked southward to the Greek city-states for support, promising them their independence from Macedonian rule; however, they had to promise not to wage war against Macedon. The struggle between the two escalated, centering on the city-state of Athens. Wisely, at the time of Antipater, Cassander had sent an emissary to Athens to ensure the city's loyalty. Later, in 318 BCE, when tensions with Polyperchon escalated, Cassander negotiated with the city, restoring its old oligarchy. To win favor with the city-states, he even rebuilt the old city of Thebes which had been destroyed by Alexander. In 317 BCE, to ensure his hold on the region, the confident Cassander established a base at Pegeus, southwest of Athens. Suffering a major defeat at Megalopolis, Polyperchon became entrapped in the Peloponnese. All the while, he continued to insist that Antipater had given him the regency, not Cassander.

With little hopes of achieving success in the city-states, Polyperchon turned northward, seeking the support of Olympias in Epirus, eventually hoping to march on Macedon, overthrow Philip III and install Alexander IV as king. Regrettably, Philip III and his wife Eurydice (also known as Adea), who had sided with Cassander and appointed him regent, were captured - and, on the orders of Olympias, he would be murdered in 317 BCE - Eurydice would commit suicide.

Despising Cassander as she had his father, Olympias quickly joined with not only Polyperchon but Eumenes as well. However, realizing the inevitable, soldiers once loyal to Polyperchon soon wavered in their support and chose to surrender and join Cassander. Added to the defeat of Eumenes, this abandonment did not help Olympias, Roxanne, and the young Alexander who were now isolated at Pydna. Polyperchon's attempts to contact her by letter or aid in an escape failed, leaving the old queen both hungry and in despair. However, Cassander, although seeking a fair trial stated that he would not harm her, in the end he received the death sentence he had always sought.

In 316 BCE he sent soldiers to kill her, and in fine Olympias fashion, she bled to death while preparing her hair and clothes. With Olympias dead, the young Alexander had no protector. To Cassander he and his mother represented a mixture of races and cultures, and though he considered keeping them as hostages for future possible negotiations, he soon changed his mind. Both Roxanne and Alexander ended their days at Amphipolis in Thrace where they were purportedly poisoned in 310 BCE. He was 13 (possibly 14) and she was only 30.

King of Macedon

By 316 BCE Cassander would be master of Macedon. To ensure his right to the throne Cassander married the half-sister of Alexander, Thessalonica. They would have three children, Philip, Alexander, and Antipater; none of them would survive to follow in their father's footsteps. The disagreement with Polyperchon would finally come to an end. Oddly, it would center on another possible claimant to the throne. The two men met on the borders of Macedon, and before the battle could begin, reached a compromise. Although never honestly considered by any regent, Alexander had a second son, Heracles, by his Persian mistress Barsine. Polyperchon, who would die in 302 BCE, agreed to kill Heracles and, as a reward, was named a major-general in the Peloponnese.

Cassander continued his fight against Antigonus from 315 to 311 BCE, finally reaching a tenuous peace agreement. In 305 he became the self-proclaimed king of the Macedonians, but at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE Cassander, Ptolemy I, Seleucus I, and Lysimachus would again battle Antigonus I and his son Demetrius I of Macedon. The latter two would be defeated, and the old commander Antigonus would die in battle. Cassander, himself, would die in 297 BCE, and for a while, Macedon was left stable. Unfortunately, without a surviving heir to carry on, his beloved Macedon fell to an enemy, Demetrius.