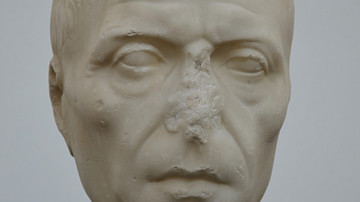

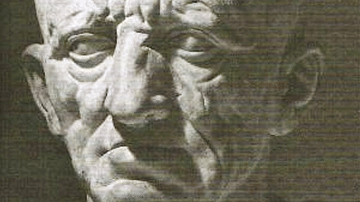

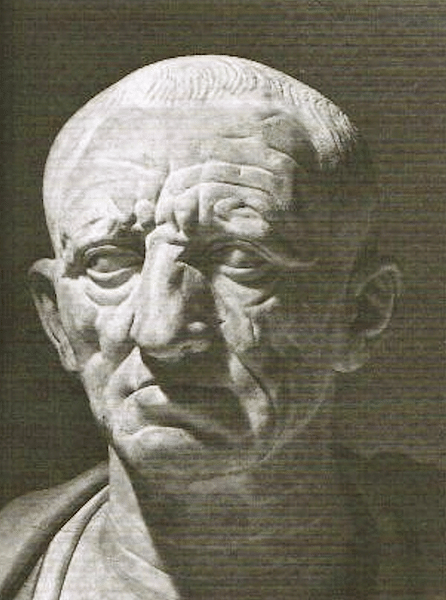

Marcus Porcius Cato, better known as Cato the Censor or Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE), was an influential political figure of the Roman Republic. Serving as quaestor, aedile, praetor, consul, and censor, he championed Roman virtues and detested Greek culture. He wrote the first Roman histories in Latin and was an eloquent orator. Towards the end of his career, he advocated for the Third Punic War with his famous line, "Carthage must be destroyed."

Early Life & Family

Cato was born in 234 BCE at Tusculum but spent most of his childhood on his family's estate in Sabine country. The historian Plutarch in his Lives wrote that "he gained, in early life, a good habit of body by working with his own hands, and living temperately, and serving in the war …" (379) Little is known of his early life before he entered the military.

Around 220 BCE, the patrician Lucius Valerius Flaccus saw something in the young farmer and took him to Rome where he would begin a life in politics. Married twice, Plutarch stated that Cato was both a good husband and father. Echoing the attitude of the time, Cato believed it was best to marry "a woman more noble than rich because she would be more obedient in all that is fit and right" (392). His eldest son died in 152 BCE, while his second son would be the grandfather of the Roman statesman and orator Cato the Younger (95-46 BCE) – hence the nickname of Cato the Elder, later ascribed Cato the Censor. Like the future Cato, Cato the Censor was considered a champion of Roman virtues; something he advocated throughout his extensive political and military career.

Political Career

Cato's climb on the cursus honorum began in the military. At an early age (Plutarch claims 17), he served during the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), earning distinction at the Battle of Metaurus in 207 BCE. Plutarch wrote that in battle "he would strike boldly, without flinching, stand firm to his ground, fix a bold countenance upon his enemies…" (379). He served as a quaestor under the hero of the Battle of Zama (202 BCE), Scipio Africanus the Elder (l. 236-183 BCE), in Italy and Africa. It was during the Second Punic War that Cato's disdain for Carthage began to emerge. Next, he was a plebeian aedile in 199 BCE and a praetor assigned to Sardinia in 198 BCE where he quashed usury. He became a consul with his old mentor Lucius Valerius Flaccus in 195 BCE where he opposed unsuccessfully the repeal of the Oppian Law (Lex Oppia), which limited not only a woman's wealth but her show of wealth. He suppressed a rebellion in Spain, extending Roman control and arranging for the exploitation of the gold and silver mines.

At the end of his military career, he served as a military tribune (some say legate) at the Battle of Thermopylae in 191 BCE against Antiochus III (r. 223-187 BCE), ruler of the Seleucid Empire. According to Philip Matyszak in his Greece Against Rome, both the Seleucids and Romans were well aware of the defeat of Leonidas and the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae in 480 BCE. And, both were equally aware of the famed pass. Knowing this, Antiochus stationed an Aetolian garrison to guard the pass that had allowed the Persian army of Xerxes I to attack Leonidas from the rear. The Romans countered; sending one column to attack the garrison while another circled around it. The second column was led by Cato, who "had a miserable time' and almost got lost. When the Romans, under the command of Marcus Glabrio, finally attacked the garrison, the sound of the battle guided Cato and his forces to attack the Seleucid rear. The battle ended with the Romans claiming only a loss of 200 men.

Censor

Cato had his detractors throughout his career. Anthony Everitt in his The Rise of Rome wrote that a "new generation of politicians (novus homo) emerged after the end of the wars with Carthage, the most able but most unlikeable of whom was Marcus Porcius Cato" (296). Adrian Goldsworthy in his Fall of Carthage said these new men "were apt themselves to exaggerate the obstacles they had overcome to add to their own achievements" (41). Cato's unpopularity became most visible when in 184 BCE he served as censor with Flaccus. The censor was usually an ex-consul and could hold the office for up to 18 months. His principal duties included surveying the lists of citizens and assessing their property and morality. They also oversaw the Roman Senate rolls, expelling anyone suspected of improper behavior – one senator was expelled for hugging his wife in public. To discourage high living, Cato imposed punitive taxes on expensive clothing, carriages, women's ornaments, and furniture.

Orator & Defender of Roman Values

According to Plutarch, Cato had a solidarity and depth of character. He was admired by those around him because while other Romans were succumbing to outside influences and "mixed customs," Cato resisted. He was considered to be one "who could cultivate the old habits … or be in love with poor clothes and homely lodgings, or could set his ambitions rather on doing without luxuries than on possessing them" (381). Best known and respected for his oratorical eloquence, he was said to be courteous and pleasant but formidable and overwhelming. His eloquence before the Senate earned him the nickname of the Roman Demosthenes.

According to Josiah Osgood in his Uncommon Wrath, Cato "championed traditional Roman values of hard work austerity, and a willingness to make any sacrifice for the public good and he attacked noble senators for failing to live up to those values" (23). Goldsworthy wrote that throughout his career "Cato presented himself as a defender of traditional Roman morals and virtue against the corrupting influence of foreign and especially Greek culture" (324).

Works

Aside from his role as a politician, Cato the Elder was also an author, writing the first historical work in Latin. The seven books of Origenes dealt with Rome in the regal period, although avoiding the early Republic. In Origenes, Cato contented that service to the state was more important than the individual. A second work – the only to remain intact – was De agri cultura. To Cato, trade was more profitable than farming but too risky, while banking was more dishonorable. In it, Cato asserted that 'the citizen with his plow and on the battlefield with sword and spear, stood for all that was best about Rome" (Everitt 296).

Although he spoke fluent Greek, in his Ad filium, he expressed his contempt for all things Greek, calling them a "vile and corrupting race". Cato attacked the corrupting influence of Greek culture, namely Greek literature and Greek philosophy, on traditional Roman behavior and morals. Although he admired the ancient Greek philosopher Socrates (l. c. 470/469-399 BCE) for having lived a temperate and contented life, he called him a "terrible prattler".

One of Cato's major political targets was the Roman commander and hero Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus the Elder under whom Cato had served as quaestor. During his time as quaestor, Cato accused Scipio of personal indulgences and overpaying his troops, money Cato claimed they spent on luxuries. Scipio's appreciation for Greek culture and the Greek language caused, according to Everitt, Cato to devote much of his time trying to discredit him. After returning from their successful battle against Antiochus III, Scipio and his brother Lucius were accused of fraud. Refusing to face the allegations, Scipio withdrew from Rome and retired to his villa.

Despite his disdain for the Greeks, Cato still recognized the Roman connection to Aeneas and the Trojan War. Everitt wrote that for Cato "there was something unforgivably Greek about the sophisticated, self-indulgence of city life" (296). But Mary Beard in her SPQR wrote that Cato's idea of "old-fashioned, no-nonsense Rome values was as much an invention of his own day as a defense of long-standing Roman tradition" (268). The Roman sense of austerity was a product of a cultural clash in a period of expansion.

Carthage Must Be Destroyed

After the Second Punic War and the defeat and exile of Hannibal (247-183 BCE), Carthage began to regain its economic strength while remaining compliant with the peace treaty signed with Rome. Around 153 BCE, Cato, now in his eighties, served as one of the representatives assigned to arbitrate a dispute between Carthage and the Numidian king Masinissa (r. 202-148 BCE), Cato was cautiously impressed by the growing wealth of the city and its economic boom. Returning to Rome, Cato served a warning to Rome: "Carthago delenda est" ("Carthage must be destroyed"). Plutarch wrote that Cato found Carthage "well-manned, full of riches and all sorts of arms and ammunition" (396). He believed that Rome should keep a careful watch on Carthage or they themselves would fall into danger.

The Numidians, under their aging king, continued encroaching on Carthaginian territory – supposedly reclaiming previously seized land. Appeals to Rome went unresolved. Finally, Carthage rose up and sent forces against Masinissa only to meet with disaster. This attack was in violation of Roman orders that the city not engage in any military action. Reacting to Cato's warning, in 149 BCE, a Roman army was dispatched to Carthage. The city submitted, surrendering 300 hostages and weapons, but when Rome demanded they rebuild their city further inland 16 km (10 mi) away from the sea – something that would destroy their ability to trade – the city resisted.

To end the Third Punic War, Rome sent forces under the consul and commander Publius Cornelius Scipio (adopted grandson of Scipio Africanus), and in 146 BCE, Carthage surrendered; the city was razed, and North Africa became a province of Rome. To many, Rome had no justification for the war or the city's annihilation. Plutarch wrote that "Cato, they say, stirred up the third and last war against the Carthaginians but no sooner was the said war begun than he died" (397).