The Celts were a linguistic group which spanned across a wide geographic area and included numerous cultures and ethnicities. Because of this fact, the traditions, practices, and lifestyles of Celtic-speaking peoples varied considerably. The importance of warfare and the traditions surrounding war were one common thread of similarities throughout Celtic societies and cultures, from the earliest emergence of the Hallstatt culture (12th-6th century BCE) to the La Tene culture (5th-1st Century BCE).

Warfare was interwoven into Celtic social structures, art, religion, and lifestyle, and the Celts acquired a warrior reputation among their neighbours in the ancient world. While Celtic societies tended to be less well-organized than their Mediterranean counterparts, Celtic craftsmen worked iron, bronze, and gold with tremendous skill, and many technological innovations related to metalworking originated with the Celts.

Warfare & Celtic Society

Relatively little is known about Celtic society due to the bias of Classical sources describing the Celts and the ambiguity of archaeological evidence. It is even apparent that the structure of Celtic societies was quite diverse, with sacral kingship, tribal coalitions, and even republican political structures existing in different times and places.

Based on archaeological evidence - some graves contain much more valuable goods than others - it is postulated that there was a hierarchical social structure and the aristocracy placed a heavy emphasis on warrior status and prestige. Early Irish literature also attests to the presence of several different social classes, including nobles, free people, and slaves.

Clientship was an important part of this society, as the aristocracy used the bonds of patronage they had with their followers to maintain their own social status. A patron would offer hospitality, legal protection, economic support, and other rewards to their followers in exchange for loyalty and service. Their followers were expected to repay them with the products of their farms, to labor for them, and to follow them into battle when called. Celts of sufficiently high status to have clients might themselves have a patron of higher status, with chieftains and even kings being clients of more powerful rulers.

Warfare and raiding offered an opportunity for individuals to improve their social standing and acquire loot with which to provide their clients. Many raids were carried out to steal cattle or treasure, the two most important sources of wealth in Celtic society. However, some raids were attempts to conquer nearby groups or polities. The competition for political power in Celtic Europe was at times violent, and kings or chieftains might attempt to forcibly subjugate other groups to increase their prestige. At other times, the defeated were compelled to offer up tribute and hostages to the victors.

Status & Funerary Rites

Proto-Celtic and Celtic burials can tell us a lot about the development of warrior culture in Central Europe. The practice of burying important individuals with objects related to warfare and status dates back to the 12th-century BCE Urnfield culture of Central Europe. So-called 'warrior burials' are distinguished from the mass of more ordinary burials in prehistoric cemeteries by the richness and significance of their burial rites.

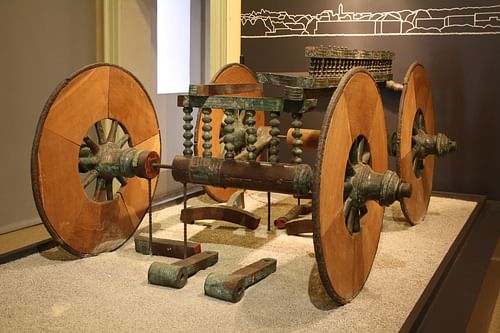

Important individuals were distinguished by the inclusion of items like horse gear and weapons, especially swords. Vehicles such as carts or wagons were also included in high-status burials, offering a precursor to the role that the chariot played in later Celtic warfare and burial rites. These objects may have been owned by the individuals in life, but the selection of items to include in a burial might also be influenced by local traditions and beliefs. For example, the placement of certain weapons or pieces of equipment may have been more ceremonial or religiously motivated. This is especially likely to be true of more ornate swords, daggers, and helmets.

The importance of horse ownership and warrior status was shared by the Hallstatt culture which developed in the same region and flourished from around the 12th century BCE to the 6th century BCE when it was succeeded by the La Tene culture. Treasures such as drinking cups and horns also played an important role in Hallstatt burial rites, and the ability to provide sumptuous feasts became a primary method of signaling power and status. This mode of distinguishing elites quickly spread and burials with Hallstatt weapons and horse gear have been found as far afield as Britain and Ireland. On the other hand, the practice of burying elites with vehicles remained localized in Central Europe, particularly Germany and Bohemia.

The warrior burials of the La Tene period date to roughly between the 6th century BCE to the 1st century BCE. La Tene warrior burials contain objects related to warfare such as swords, spears, and helmets, as well as drinking ware related to feasting. More important individuals were buried with horses or chariots.

A kind of hierarchy of warriors appears on the Gundestrup Cauldron from Jutland, Denmark. This scene is often interpreted as portraying a belief in an afterlife where individuals could advance in social status. On the bottom register, a line of spearmen marches on foot towards a giant figure, probably a god related to war. A man with a boar-crested helmet and a sword follows the spearmen, and behind him are three carnyx (a wind instrument) players. At the far left, the oversized god dips a man into a cauldron of rebirth. In the top register, a bunch of warriors or chieftains on horseback ride away from the god.

Horses & Chariots in Celtic Warfare

The Celts were renowned for their skill on horseback, and horses played an important role in Celtic culture. The importance of horse ownership and charioteering to social status and wealth in Celtic culture is a testament to the role of mounted warfare in Celtic Europe.

Pausanias (c. 110 - c. 180 BCE) describes a tactic called trimarcisia in his Description of Greece, in which each mounted warrior would be accompanied by two grooms who each had a horse in case their master's horse was wounded. If the warrior was wounded, one of the grooms would return him to their camp, while the other one remained to fight in his place. (Pausanias, 10.19.6)

Roman sources describe the Celts bringing both wagons and chariots into battle, and these vehicles have been found in Iron Age Celtic burials associated with warriors. Two-wheeled chariots drawn by a team of two horses are known from both archaeological and artistic evidence such as coins and burials. According to Romans, the Celts used their chariots to get into the fray and intimidate their enemies before jumping off and fighting on foot.

[The Britons'] mode of fighting with their chariots is this: firstly, they drive about in all directions and throw their weapons and generally break the ranks of the enemy with the very dread of their horses and the noise of their wheels; and when they have worked themselves in between the troops of horse, leap from their chariots and engage on foot. (Caesar, Gal., 4.33)

Roman authors like Lucan (39-65 CE), Pomponius Mela (c. 43 CE), and Silius Italicus (c. 28 - c. 103 CE) describe the Celts as riding scythed chariots into battle and the Byzantine historian Jordanes (c. 6th century CE) made a similar claim about the Britons in his Getica. Although there is no evidence that the Celts used scythed chariots, their use is described in the 8th-century CE Irish epic The Cattle Raid of Cooley (Táin Bó Cúailnge), which is set in the 1st century CE.

When the spasm had run through the high hero Cúchulainn he stepped into his sickle war-chariot that bristled with points of iron and narrow blades, with hooks and hard prongs, and heroic frontal spikes, with ripping instruments and tearing nails on its shafts and straps and loops and cords. The body of the chariot was spare and slight and erect, fitted for the feats of a champion, with space for the lordly warrior's eight weapons, speedy as the wind or as a swallow or a deer darting over the level plain. The chariot was settled down on two fast steeds, wild and wicked, neat-headed and narrow bodied, with slender quarters and roan breast, firm in hoof and harness—a notable sight in the trim chariot-shafts. (Kinsella and Le Brocquy, 153)

By the 1st century BCE, chariots had begun to phase out of use in continental Europe, gradually being replaced by mounted soldiers. Britain and Ireland were more isolated from the changes in warfare which affected the continent, and British tribes continued to use chariots well into the Roman period. War chariots are attested to during the invasion of Britain by Julius Caesar (100 - 44 BCE) in 54 BCE, and the Caledonians of modern day Scotland are described as using war chariots at the Battle of Mons Graupius in 83 CE. The noise and clamor of Celtic chariots is remarked upon by both Caesar and Tacitus (c. 55 - 120 CE).

The Evolution of Celtic Arms & Armor

The Celtic panoply generally consisted of a sword, spears, and a shield. The main sources of evidence about ancient Celtic arms and armor come from archaeological finds, Greek and Roman literary accounts, and art depicting Celtic warriors.

The Celts are known for having used long oval shields which were long enough to protect the greater part of the body. These were decorated with bronze or iron bosses, some of which were quite ornate such as the 'Battersea Shield'. Swords were worn on the hip or side, hanging from a bronze or iron chain. Different types of spears were used, with some lighter javelins being thrown from horseback, while larger spears were used as lances.

The spears they brandish, which they call lanciae, have iron heads a cubit in length and even more, and a little under two palms in breadth; for their swords are not shorter than the javelins of other peoples, and the heads of their javelins are larger than the swords of others. (Diod. Sic. 5.30.3)

Composite armor made of fabric or leather, not unlike the Greek linothorax, is portrayed in Celtic art and was certainly used. As early as the 4th century BCE, chain mail was prevalent among Celtic warriors, and many Classical depictions of Celts portray them wearing mail shirts. Chain mail has been found in Late Iron Age burials from Western, Central, and especially Eastern Europe. The Romans likely first encountered chain armor in areas with Celtic presences like northern Italy, and chain mail may have originated among the Celts before spreading to Europe and Asia Minor as the Roman author Varro (116 - 27 BCE) claimed.

These shirts were made with thousands of interlocking iron circles and allowed the wearer more freedom of movement than solid bronze or iron cuirasses. Surviving examples of Celtic mail shirts are typically long, falling just below the waist and they would have weighed more than 14 kg (about 32 pounds). To help redistribute the weight of the iron mail, they were made with broad shoulder straps which had the benefit of adding extra protection.

A few surviving examples of breastplates have also been found in Hallstatt and La Tene graves, although these were very rare. The Stična Breastplate is a riveted bronze cuirass from a 6th century BCE Hallstatt warrior's grave in modern-day Slovenia. Similar cuirasses have been found in 8th-century BCE Hallstatt burials in Marmesse, France. These cuirasses bear some similarity to Greek and Etruscan 'bell cuirasses' produced in the Mediterranean during the Archaic Period (8th to 6th century BCE) and to the 'muscle cuirass' which developed in the 5th century BCE. The 1st-century BCE 'Warrior of Grezan', one of the oldest and best examples of Celtic art depicting a warrior, may depict the figure wearing a breastplate.

La Tene helmets of various shapes and designs appear in graves from the 5th century BCE on. However, Celtic helmets are rare, and it is likely that helmets were not widely used by some tribes. Their scarcity backs up Greek and Roman claims that some Celtic tribes scorned the use of helmets. The only area where significant numbers of Celtic helmets have been found is Italy.

Many surviving examples of Celtic helmets are ceremonial and were not intended for use in actual combat. These were status symbols, made with expensive materials like gold and coral in addition to bronze and iron. The often impractical designs indicate that they were intended to make the wearer more visible in parades or processions, rather than to provide protection in actual combat. Celtic helmets began to be less ornate and more practical in the later La Tene period, perhaps indicating that their use was becoming more widespread.

Celtic Warriors in the Greco-Roman Imagination

Celtic warriors played an increasingly prominent role in the art and literature of the Greeks and Romans from the 4th century BCE onwards. A coalition of Celtic tribes under a high king known as Brennus invaded Italy and sacked Rome in 390 BCE, and another ruler called Brennus helped to lead an invasion of Southeastern Europe with a coalition of tribes which culminated in the invasion of Greece c. 280 BCE. 'Brennus' was probably originally a Celtic title which became corrupted and misinterpreted as a name by Greek and Roman writers. The aggressive migration of the Celts into the Mediterranean led to increasingly intense conflicts with the Hellenistic kingdoms and the Roman Republic.

Greek and Roman authors describing conflicts with Celtic tribes noted the differences in Celtic tactics and equipment. However, these accounts are heavily colored by bias and exaggeration. Celtic tactics were generally denigrated as inferior, feeding into Greco-Roman stereotypes about northern peoples being wild and unintelligent. Celtic warriors were considered to have foolhardy courage in battle, which could quickly turn to panic when the battle turned against them. Greek and Roman authors accused the Celts of barbarous and brutal behavior such as human sacrifice and even cannibalism. While human sacrifice was practiced to some extent in Celtic cultures, stories like Pausanias' account of Celts eating Greek babies when they sacked Callium in 279 BCE are pure fiction.

Celtic arms and armor were adopted by the groups they came into conflict with such as the Thracians and the Romans. The Roman gladius is an important example of this, as it was descended from Celtic or Celtiberian swords which could be used for both cutting and thrusting. The gladius replaced the more pointed, blunt-edged swords that Romans had used until the 3rd century BCE. There are several theories regarding this, including the idea that the gladius was introduced by Celtiberian tribes in the Iberian Peninsula, by Celtic or Celtiberian mercenaries fighting for Hannibal in the Second Punic War, or by Gallic tribes in Europe.

The later adoption of the spatha, a longer sword than the gladius, was largely due to the increasing numbers of Celtic cavalry auxiliaries in the 2nd to 3rd century CE Roman army, and changes in Roman tactics. Other examples of Celtic arms adopted by the Romans are the Montefortino and Coolus helmet-types.

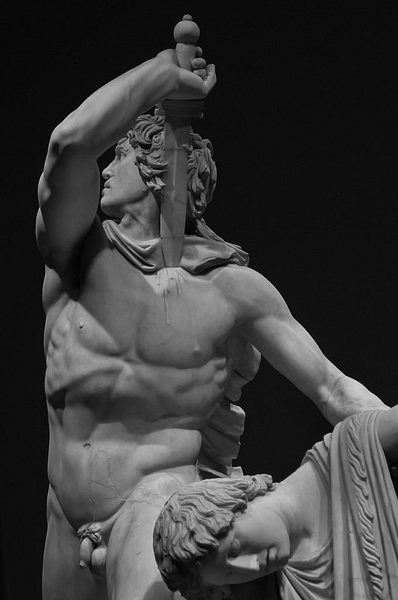

The image of undisciplined, savage hordes massing on the edges of the empire was cultivated by Greco-Roman authors who wanted to contrast their own self-proclaimed civility with the barbarism of foreign peoples. Many of the more famous examples of Classical art depict Celts in the nude, signifying their supposed barbarity. The 'Dying Gaul' and the 'Ludovisi Gaul Killing His Wife' are two examples of Classical art which use nudity to express the barbarity of their subjects, although they also idealize their nobility in defeat. Some ancient Roman authors claimed that they charged into battle fully naked, rumors which probably inspired artistic representations of nude Celtic warriors.

“Some of them have iron cuirasses, chain-wrought, but others are satisfied with the armour which Nature has given them and go into battle naked.” (Diod. Sic., 5.30.3)

These Classical stereotypes of the Celts were the underpinnings of early historical scholarship and still inform public perception of the Celts to a great degree. Although archaeological evidence has disproven many of these ideas, they still linger on in the modern imagination.

- Previously published as "Ancient Celtic Warfare" on Magna Celtae.