Chacchoben (pronounced chac-CHO-bin) is a Maya site dated to c. 700 located in the state of Quintana Roo, Mexico. Once a large and significant urban religious center, the city was abandoned c. 900-950 CE at about the same time as the other great cities of the Maya were and was steadily swallowed up by the surrounding forest. The ruins were discovered in 1942 by a farmer who built his house nearby and protected the site until 1972 when an American archaeologist discovered it and brought it to the government's attention. The name Chacchoben is a modern-day designation meaning "Place of the Red Corn". The name of the city in antiquity is unknown.

Only partially excavated, the site features four grand temples and the ruins of the marketplace and residential quarter. Other structures remain buried under vegetation but have been identified tentatively as temples, indicating that Chacchoben was once an important religious center. A suggestion of the size of the city is that one of the enormous structures excavated at the site is designated Temple 24. Archaeologists note that this is only the number of temples cautiously identified thus far, not the possible total and not counting other buildings. Items such as incense burners found at one of the temples make clear that people continued to visit and worship at the site long after it was abandoned. Today Chacchoben is an archaeological park open to the public.

Early Settlement & Construction

The site shows evidence of human habitation dating back to c. 200 BCE but the surrounding area (known as the Region of the Lakes) was settled much earlier in c. 1000 BCE. The lakes, lagoons, and marshes provided the people with freshwater, fish, and game, and the city's builders most likely initially lived in small thatched huts. Sometime c. 700, the city was completed but why such an enormous complex was constructed and what precisely its religious significance was is unknown. As with other Maya sites, the reasons for its abandonment are equally unclear but may have had to do with overpopulation, overuse of the land, or military conquest.

Chacchoben was built in the Peten style of architecture seen at more famous sites such as Uxmal and Palenque but with a notable difference: there is no ornamentation to the structures. The buildings and temples at Maya sites such as Tulum, only 110 miles (177 km) to the north, Uxmal, Chichen Itza, and many others are highly ornamented while those at Chacchoben are austere. While it is certainly possible that the temples and other structures not yet uncovered are as lavishly decorated as those at other sites, this seems unlikely because those which have been excavated were clearly of great importance.

The structures and areas excavated at the site are:

- Temple 24 and Plaza B

- The Gran Plaza (Great Plaza)

- The Gran Basamento (Great Basement)

- Templo de Las Vasijas (Temple of the Vessels)

- Templo 1 (Temple 1)

- Templo de Las Vias (Temple of the Ways)

Presently, these buildings are surrounded by forests but once would have been only a small part of a vast complex of temples, homes, and administrative centers.

Temple 24 & Plaza B

Temple 24 is a massive step pyramid built in the architectural style of the Classic Maya Period (250-950) and located in Plaza B. The Maya perfected the use of hydraulic cement sometime prior to 250 BCE. Kilns converted their abundant supply of limestone to powdered cement which, when mixed with water, stones, and clay, became concrete. Temple 24 exhibits the skill of the ancient workers in the fine use of concrete between the layers of stone.

When a new ruler came to the throne, he would build his palace and temple on top of the old king's work. This was a practical show of power - the new king had dominated the old - but could also be symbolic as the new king was acknowledging the foundation of power he built on. Temple 24 follows this paradigm as the present structure is built on an older one.

At many sites, such as Kohunlich, archaeologists can date a city by the inscriptions left on these structures by the series of kings. Another unusual aspect of Chacchoben, besides no ornamentation, is that it has no inscriptions. Temple 24 is only known to have been built on an earlier temple because of the difference in age of the concrete and an alteration in the pattern of the placement of the stones.

The Plaza & the Temples of Gran Basamento

The Great Plaza was the marketplace and center of the city, divided by a broad thoroughfare. The ruins of the ancient market stalls and residences of the upper class are still visible to either side of this roadway, though many are obscured by vegetation. Maya cities engaged in trade with each other and most likely imports would have been offered at the city's market but, just like in the modern day, would have been more expensive and only available to the upper class. The goods regularly sold in the marketplace would have mostly been the everyday necessities and small luxuries anyone could afford.

The upper class in any Maya city lived in stone houses in the center while the lower-class poor found homes in thatched huts on the outskirts of the city. This same paradigm is evident at Chacchoben where the stone houses lining the main street belonged to the wealthier citizens. Although the plaza appears narrow today, due to the forest's encroachment, it was quite wide in its time and included the ball court (a standard feature of Maya cities) where the Mesoamerican ball game of Poc-a-Toc was played.

A broad stairway, close-cut from the rock of the nearby hill, leads up from the Great Plaza to the so-called Great Basement, a plateau featuring the Temple of the Vessels, Temple 1, and a few ruins of the foundations of smaller buildings. Astronomy and astrology were of equal importance to the Maya and their cities were constructed in accordance with celestial alignment. At the top of these stairs are two stone pillars known as Los Gemelos (the twins). One of the pillars has a hole drilled through it which focuses the setting sun at the winter solstice on a small area in the Great Plaza. Archaeologists believe there was once a statue or stele at this spot which this beam of sunlight would have illuminated. In this same way, at the summer solstice, the dawn sunlight is focused through the top of Temple 1, illuminating a now-vacant spot on the ground for a full five minutes.

The Great Basement plateau was an important site for religious rituals conducted at Temple 1; the various cups, pitchers, bowls, and plates used in these rituals were housed in the Temple of the Vessels nearby. The smaller buildings, which are nothing more than a few stones, outlines in the earth, or foundation walls today, were probably the homes of the priests and temple workers.

Maya religion was completely integrated into the people's daily lives. The gods were always present but lived apart from human beings high on mountain tops or deep in caves. The Maya built their enormous pyramids in the centers of their cities as artificial mountains, the homes of the gods, and placed the temples at the top. The gods, it was thought, would recognize these monuments as their natural homes and live among the people.

They also created artificial caves within these monuments for the same reason. These "caves" were sometimes tombs but more often small temples with altars for sacrificial offerings. As with many ancient cultures, the Maya believed the gods were constantly providing for and caring for them but, unlike most, the gods offered no guarantee to anyone of an eternal afterlife of bliss.

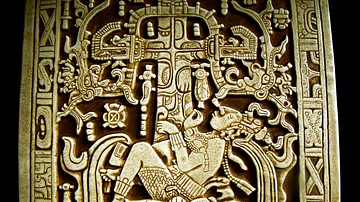

To the Maya, life was a journey, which did not end when the body died. The soul lived on and traveled to the dark underworld of Xibalba. In this land of eternal night, the soul would try to find its way through the labyrinths, avoid the tricks and traps of the underworld deities, and locate the tree of life whose roots grew deep into the shadowy earth. Once the soul reached the tree, one could climb up through the nine layers of darkness to emerge back on earth and then keep climbing up to paradise.

The only souls who were exempt from this journey were those of women who died in childbirth, voluntary sacrificial victims, warriors who died in battle, athletes who died playing the game of Poc-a-Toc, and suicides. The Maya considered the act of suicide rational and honorable and even had a goddess (Ixtab) dedicated to the care of these souls.

It was enough for the Maya that the gods gave people life and sustenance while they lived; they weren't expected to have to continue guiding someone after death. That job fell to others such as the souls of dead relatives, supernatural entities, or to spirit-dogs. Dogs were regarded highly by the Maya, at the same time they were a food source, because of their relationship with the divine. The dog was neither fully wild nor completely domesticated and so was considered a kind of link between the world of humanity and that of the gods.

Sacrifices, including human sacrifice, are thought to have been conducted at Temple 1. Since blood was the food of the gods, it would have been caught in bowls or pitchers brought from the Temple of the Vessels and then "fed" to a statue or image of a god at Temple 1.

The Temple of the Ways

Returning down the stairs from the Gran Basamento and walking down the ancient main street, one comes to the Temple of the Ways, dedicated to the guardian spirits who assisted each individual through life. In Maya belief, the Ways (also known as Wayobs) are protective spirits who guide the living. The Maya believe that every day has its own particular energy conducive to one pursuit or another. If the energy of a day lends itself to work, one will be more productive than if the day's energy is better suited to recreation. Every person has a Way who helps them through their lives, calling their attention to the energy of a day, and will also guide them in the afterlife through Xibalba.

Ways appear in dreams with messages from the spirit world and, in the dream, one is brought to the Wayib (the dreaming place) where one is allowed to converse with the gods and the souls of the departed. The Temple of the Ways may have been an incubation house, such as the ancient Egyptians had, where one would go for the solution to a problem.

In ancient Egypt, if a woman were having difficulty conceiving, she would go to an incubation house of the fertility god Bes where he would visit her and take care of the problem. In this same way, a Maya might visit the Temple of the Ways to make clearer contact with their particular Way and resolve some difficulty or receive a message about the future.

Chacchoben continued as an important center for pilgrimage even after the city was abandoned. Incense burners were discovered at the Temple of the Ways during excavation dating from c. 950 through 1518 when the Spanish explorers and their missionaries first arrived. Although there is no documentation for the claim, it is possible that Chacchoben was as vital a religious center as Tantun Cuzamil on the island of Cozumel, known today as San Gervasio, where the goddess Ix Chel once spoke from her statue to the people.

Tantun Cuzamil was the most popular pilgrimage site in the era of the ancient Maya and this is well documented. Even so, the incense burners and other items found at Chacchoben strongly suggest the site had deep religious significance for the people in the surrounding area who continued to make pilgrimages to at least this one temple long after the city was left to the forest and wild animals. This site, therefore, could have been equally popular, or even more so, than Tantun Cuzamil.

Discovery

With the European colonization of the Americas from the 16th century and the resultant conversion of the Maya to Christianity, Chacchoben was forgotten and disappeared under vines, trees, moss, and other growth. In 1942, a man named Servilliano Cohuo, a Yucatec Maya, was looking for a place to start his farm. He wandered into the outskirts of the jungle and found himself in the middle of an ancient city obscured under centuries of growth. Cohuo cleared a part of the site, built himself a house, plowed the land, and began his farm. He married and had children who grew up playing in the ruins as their backyard.

Years later, in 1972, Dr. Peter Harrison, an American archaeologist, was flying over the region in a helicopter and noticed something strange about the topography below him: there were large hills in an otherwise flat region. Harrison went to explore the area and found Cohuo and his family. Cohuo was only too pleased to show the archaeologist around the site but could tell him nothing about it.

It was Harrison who first dated human habitation in the surrounding area at c. 1000 BCE and early structural development at the site to c. 200 BCE. Cohuo gave Harrison permission to inform the Mexican government that the ruins existed and Harrison did so, requesting that Cohuo be allowed to remain on his farm for the rest of his life. Harrison then made the first professional excavation of the site and mapped it.

In 1978, Cohuo was made the official guardian of Chacchoben as excavations continued to uncover more of the ancient city and attracted the curious. He died in 1991, and, with his death, his family had to leave their home and were relocated nearby. The Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History took charge of excavation and restoring the site in 1994.

It was opened to the public in 2002 and has become increasingly popular as a tourist attraction since. The meaning of the ancient city for its builders remains unknown as the magnificent ruins looming in the Mexican forest are so far silent on that, but this is precisely what makes the site so alluring to tourists: people love a mystery and there are few Maya sites as mysterious as Chacchoben.

Author's Note: Aspects of this piece appeared in the article The Mysterious Treasure of Chacchoben by Joshua J. Mark published by Timeless Travels Magazine, Summer 2017.