Chaco Canyon was the center of a pre-Columbian civilization flourishing in the San Juan Basin of the American Southwest from the 9th to the 12th century CE. Chacoan civilization represents a singular period in the history of an ancient people now referred to as "Ancestral Puebloans" given their relation to modern indigenous peoples of the Southwest whose lives are organized around Pueblos, or apartment-style communal dwellings.

Chacoans built epic works of public architecture which were without precedent in the prehistoric North American world and which remained unparalleled in size and complexity until historic times - a feat which required long-term planning and significant social organization. Precise alignment of these buildings with the cardinal directions and with the cyclical positions of the sun and moon, along with an abundance of exotic trade items found within these buildings, serve as an indication that Chaco was an advanced society with deep spiritual connections to the surrounding landscape.

Making this cultural fluorescence all the more remarkable is that it took place in the high-altitude semi-arid desert of the Colorado Plateau where even survival marks an accomplishment and that the long-term planning and organization it involved was carried out without a written language. This lack of a written record also contributes to a certain mystique surrounding Chaco - with evidence limited to objects and structures left behind, many tantalizingly significant questions about Chacoan society remain only partially answered despite decades of study.

Early Settlement

The first evidence of long-term human settlement in Chaco Canyon dates to the 3rd century CE with the construction of partially subterranean homes known as pithouses, structures which eventually were clustered together to form large villages. As inhabitants became increasingly integrated, single-story multi-room buildings began to appear in the 8th century CE among pithouse villages. Then, c. 850 CE, a remarkable change in Chacoan architecture began to take place which set it apart from that of any other Southwestern area. Whereas most contemporary buildings in the region contained less than ten rooms and were built out of wooden posts and adobe, Chacoans began to construct "great houses," colossal sandstone masonry structures which used thick walls to support multiple stories and hundreds of rooms. What it was that prompted such a dramatic and labor-intensive shift remains unknown today.

Great Houses

One of the earliest constructed and most magnificent of great houses found within the canyon's walls is referred to as Pueblo Bonito, a Spanish name given by Carravahal, a Mexican guide who accompanied a U.S. Army topographical engineer making a survey of the region in 1849 CE (names of many structures, including the canyon itself, are Spanish in origin or are derived from Spanish transliterations of names assigned by the Navajo, a Native American people whose land surrounds the canyon). Pueblo Bonito was planned and constructed in phases over the course of three centuries. It grew to include four or five stories in parts, more than 600 rooms, and an area of more than two acres, all while maintaining its originally-designed D-shaped layout.

Without a definitive record, many interpretations of the role these structures played have arisen. The likelihood that great houses had predominantly public purposes - accommodating intermittent influxes of people visiting the canyon to partake in ceremonies and commerce while serving as public gathering places, administrative centers, burial grounds, and storage facilities - is now widely accepted. Based on the presence of habitable rooms, it is likely these complexes also supported a limited number of year-round, presumably elite, residents.

In addition to their immensity, great houses shared several architectural characteristics reflective of their public role. Many included a large plaza, enclosed by a single-story line of rooms to the south and multi-story room blocks to the north, stepping from a single story at the plaza upward to the highest story at the back wall. At Chetro Ketl, another monumental great house within the canyon, the plaza feature is made even more impressive through its artificial elevation more than 3.5 meters above the canyon floor - a feat requiring the hauling of tons of dirt and rock without the assistance of draft animals or wheeled vehicles. Incorporated into the plazas and room blocks of great houses were large, round, usually subterranean chambers known as "kivas." Based on the use of similar structures by modern Puebloan peoples, these rooms were likely communal spaces used during ceremonies and meetings, with a fire pit at the center and access to the room provided by a ladder extending through a smoke hole in the roof. Oversized kivas, or "great kivas," were capable of accommodating hundreds of people and when not incorporated into a great house complex, they stood alone, often forming a central space for surrounding communities composed of (relatively) small houses.

To support multi-story great house constructions, which contained rooms with floor areas and ceiling heights much higher than those of preexisting dwellings, Chacoans created massive walls using a version of the "core-and-veneer" technique. An inner core of roughly-hewn sandstone held together with mud mortar formed the core to which thinner facing stones were attached to form a veneer. These walls were in some cases nearly one meter thick at the base, tapering as they rose to reduce weight - an indication that builders planned the higher stories during the construction of the first. Although today these mosaic-style veneers are visible, contributing to the striking beauty of these buildings, Chacoans applied plaster to many interior and exterior walls once construction was complete to protect the mud mortar from water damage.

The construction of structures of this size required an enormous amount of three essential materials: sandstone, water, and timber. Using stone tools, Chacoans quarried then shaped and faced sandstone from canyon walls, preferring during initial construction hard and dark-colored tabular stone at the top of cliffs, transitioning as styles shifted during later construction to softer and larger tan-colored stone located lower on cliffs. Water, required along with sand, silt, and clay to create mud mortar and plaster, was marginal and available primarily in the form of brief and often torrential summer thunderstorms. In addition to natural sandstone reservoirs, rainwater was captured in wells and dammed areas created in the arroyo (an intermittently flowing stream) that carved the canyon, Chaco Wash, and in ponds to which runoff was directed via a series of ditches.

Sources of timber, required for the construction of roofs and upper story floors, were once present in the canyon but disappeared around the time of the Chacoan fluorescence due to drought or deforestation. As a result, Chacoans traveled on foot 80 kilometers to coniferous forests to the south and to the west, cutting down trees then peeling and leaving them to dry for an extended period to reduce weight, before returning and carrying each back to the canyon. This was no small task considering that the carrying of each tree would have required a several days' journey by a team of people and that more than 200,000 trees were used over the three centuries of construction and repair of the roughly dozen major great house and great kiva sites within the canyon.

Planned Landscape

Although Chaco Canyon contained a high density of architecture of a size never before seen in the region, the canyon was only a small piece located at the center of a vast interconnected area which formed Chacoan civilization. More than 200 communities with great houses and great kivas using the same distinct masonry style and design as those located within the canyon, albeit on a smaller scale, existed beyond the canyon. While these sites were most numerous within the San Juan Basin, in total they encompassed a portion of the Colorado Plateau larger than the area of England.

To help link these sites to the canyon and to one another, Chacoans constructed an elaborate system of roads by excavating and leveling the underlying ground, in some cases adding earthen or masonry curbs for support. These roads commonly originated at great houses within the canyon and beyond, radiating outward in remarkably straight sections. Chacoans maintained the linearity of these roads even when steep landforms common to the American Southwest (e.g., mesas and buttes) intersected their path, choosing instead to construct stairways or ramps onto cliff faces. Given the high inconvenience of such an approach, along with the fact that many roads did not have apparent destinations and were built wider than required for transportation by foot (many were 9 meters across), it is possible the roads served a primarily symbolic or spiritual purpose, an entrance of sorts to great houses, guiding pilgrims traveling to ceremonies or other gatherings. To enable more rapid communication, some great houses were placed within line of sight of one another and of shrines on nearby mesa tops, allowing for the signaling of other houses and of distant regions using fire or the reflection of sunlight.

Adding further structure and interconnection to the Chacoan world was the widespread practice of aligning buildings and roads with the cardinal directions and with the positions of the sun and moon during pivotal times such as solstices, equinoxes, and lunar standstills. For instance, the front wall and wall dividing the plaza of the great house Pueblo Bonito are aligned east-west and north-south respectively, while the site is located precisely west of Chetro Ketl. Casa Rinconada, a 19-meter diameter great kiva located within the canyon, has two opposing interior T-shaped doors placed along a north-south axis and two exterior doors aligned east-west, through which the light of the rising sun passes directly only on the morning of an equinox (whether this latter alignment existed during Chacoan times is uncertain given restoration work which took place in the first half of the 20th century CE).

Other sites appear to have served as observatories, allowing Chacoans to mark the progression of the sun ahead of each solstice and equinox, information potentially used in the planning of agricultural and ceremonial activities. Perhaps the most famous of these are the "Sun Dagger" petroglyphs (rock images created by carving or the like) located at Fajada Butte, a tall isolated landform at the eastern entrance of the canyon. At the top, two spiral petroglyphs exist which were either bisected or framed by shafts of sunlight ("daggers") passing between three slabs of rock in front of the spirals on the day of each solstice and equinox. Further evidence of Chacoans' celestial awareness comes in the form of several pictographs (rock images created by painting or the like) located on a section of the canyon wall. One pictograph is of a star potentially representing a supernova occurring in 1054 CE, an event which would have been bright enough to be visible during the day for an extended period. The close location of another pictograph of a crescent moon lends credibility to this theory as the moon was in its waning crescent phase and appeared close in the sky to the supernova during its time of peak brightness.

Agriculture & Trade

At an elevation of approximately two kilometers, winter in Chaco Canyon is long and brutally cold, shortening the growing season, while summers are scorchingly hot. Temperatures shift by up to 27 degrees Celsius in a single day, requiring both firewood to stay warm during the night and water to stay hydrated during the day, something difficult to manage with the near absence of trees in the canyon and the climatic alternation between drought and excess rain. Despite this unpredictability, Chacoans managed to grow the Mesoamerican triumvirate - corn, then later beans and squash - by using various dry farming techniques, evidenced by the presence of terraced land and irrigation systems. However, given the scarcity of resources within the canyon and beyond, much of what was required for daily life, including some amount of food, was imported.

Regional trade resulted in the importation to the canyon of ceramic vessels used for storage, hard sedimentary rock and volcanic stone used to make sharp tools or projectile points, turquoise turned into ornaments and inlays by Chacoan artisans, and domesticated turkeys whose bones were used to make tools and whose feathers were used to make warm blankets. As Chacoan society grew in complexity and size, reaching its zenith toward the end of the 11th century CE, so too did the extent of its trade network. Chacoans imported exotic objects and animals via trade routes that stretched west toward the Gulf of California and south more than 1000 kilometers along the coast of Mexico - seashells used to form trumpets, copper bells, cacao (the key ingredient of chocolate), and scarlet macaws (parrots with vibrant red, yellow, and blue feathers) kept as pets within great house walls.

Ritual

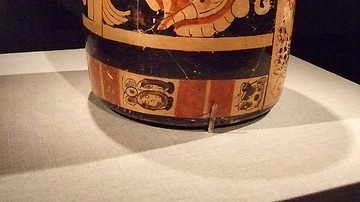

The presence of cacao provides evidence of a transfer not only of tangible goods but of ideas from Mesoamerica to Chaco. Cacao was revered by the Maya civilization who used it to make beverages which were frothed by pouring back and forth between jars before consuming during rituals reserved for the elite. Traces of cacao residue were found on potsherds in the canyon likely from tall cylindrical jars which were located in sets nearby and which are similar in form to those used during Maya rituals.

It is likely that many of these extravagant trade items, in addition to cacao, played a ceremonial role. They were found predominantly at great houses in enormous quantities within storerooms and burial rooms, alongside items with ritual connotations - carved wooden staffs and flutes and animal effigies. At Pueblo Bonito alone, one room was found to contain more than 50,000 pieces of turquoise, another 4,000 pieces of jet (a dark-colored sedimentary rock) and 14 macaw skeletons.

Abandonment

Collections of tree ring data indicate great house construction ceased c. 1130 CE, coinciding with the beginning of a 50-year drought in the San Juan Basin. With life at Chaco already marginal during periods of average rainfall, an extended drought would have strained resources and set in motion the decline of the civilization and the migration from the canyon and many outlying sites, which concluded by the middle of the 13th century CE. Evidence of the sealing off of great house doors and the burning of great kivas indicates a possible spiritual acceptance of this change in circumstances - a prospect made more likely by the integral part migration plays in the origin stories of Puebloan peoples.

Chacoans migrated to surrounding communities to the north, south, and west with less marginal environments, which reflected Chacoan influence during this time. Extended droughts, persisting into the 13th century CE, prevented the re-creation of an integrated system similar to that of Chaco and contributed to the dispersal of Chacoan peoples across the Southwest. Their descendants, modern Puebloan peoples living primarily in the U.S. states of Arizona and New Mexico, consider Chaco to be a part of their ancestral homeland - a connection affirmed by oral history traditions passed down from generation to generation.

Legacy

In the second half of the 19th century CE, significant vandalism took place in the canyon, with visitors knocking down sections of great house walls, gaining access to rooms, and removing their contents. The effect of the damage became apparent in archaeological excavations and surveys beginning in 1896 CE, which led to the formation of the Chaco Canyon National Monument in 1907 CE, halting unchecked looting and enabling systematic archaeological studies to be conducted. The monument was expanded and renamed the Chaco Culture National Historical Park in 1980 CE and was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1987 CE. Puebloan descendants maintain their connection to a land which serves as a living memory of their shared past by returning to honor the spirits of their ancestors.