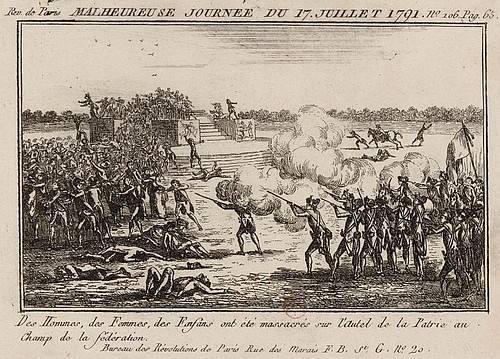

The Champ de Mars Massacre was an incident that took place on 17 July 1791, when soldiers of the National Guard under the Marquis de Lafayette opened fire on a crowd of demonstrators, who were calling for a referendum on the king's abdication and the establishment of a republic. It was a major turning point in the French Revolution (1789-99).

Whereas the idea of a French republic had been practically unthinkable earlier in the Revolution, King Louis XVI of France's (r. 1774-92) flight to Varennes on the night of 20-21 June 1791 popularized the idea, as many citizens believed the king had betrayed France and could no longer be trusted. Spurred on by the radical Cordeliers Club, over 50,000 people gathered on the Champ de Mars to sign a petition calling for the king's abdication, and for the people to decide whether there should be another monarch to replace him. Paris mayor Jean Sylvain Bailly, looking to restore order, instituted martial law and ordered the National Guard to disperse the demonstrators, which resulted in the massacre. The incident permanently damaged the reputations of both Bailly and Lafayette and hindered the cause of the constitutional monarchist faction.

The King Escapes

For the servants of the Tuileries Palace in Paris, the morning of 21 June 1791 began like any other. At exactly 7 am, two of the royal valets, the older Lemoine and the boy Hubert, went into Louis XVI's chambers to rouse the king for his morning routine. But when they pulled back his bed curtains, they were met with a surprise: the king's bed was empty. Nervously, they then made their way to the dauphin's room, which was also deserted. With growing apprehension, Hubert suggested that they should raise the alarm, or at least inform the queen. Lemoine was appalled by this thought; as a senior royal servant, he knew that court protocol was sacred. It would not be time to wake Her Majesty for another half hour. Yet when the hour rolled around, it was discovered that Marie Antoinette, too, was gone. Now, even the stuffy Lemoine could panic (Fraser, 333).

By 11 am, news of the royal family's departure had spread far and wide throughout Paris. Great crowds had assembled outside the gates of the Tuileries, shouting hateful insults at the palace walls, contained in their rage only by the assemblage of the National Guards. The Guards' commander, Gilbert du Motier, marquis de Lafayette (1757-1834), was especially mortified; the king's safety had been his responsibility. "The birds have flown," said an anxious Lafayette to his friend, the radical Englishman Thomas Paine, that morning. In response, Paine, a republican who had famously urged the 13 American colonies to throw off the tyranny of British rule, merely shrugged. "Let them go," he said (Fraser, 333).

Later that day, the royal family would be caught in the town of Varennes-en-Argonne, and by 25 June, they would be back in Paris, having been escorted by a mix of National Guardsmen and devoted French patriots. Tension lay heavy in the Parisian air, as hundreds of silent citizens watched their supposed citizen-king go past. Their silence had been orchestrated by the vexed Lafayette himself, who had posted signs throughout the city that warned: "whoever applauds the king shall be flogged; whoever insults him shall be hanged" (Fraser, 344). Yet, there could be no mistake that these Parisians felt betrayed. Louis XVI had been caught on his way to the border with the Austrian Netherlands. Had he meant to rendezvous with an Austrian army? Would he have led that army against his own people? A letter had been found in the king's chambers, in which Louis XVI vehemently denounced the Jacobins, the Revolution, and the reforms it had made thus far. How could such a king ever be trusted again?

It was left to the National Constituent Assembly to assume the task of damage control. Their official position, released to the public in a proclamation on 22 June, was that the king had been kidnapped against his will and that the scathing anti-revolutionary letter he had left behind had been planted by his devious ministers. This excuse was utter nonsense and went against all evidence, yet it was a necessary lie. The Assembly was close to finishing the constitution it had been laboring over for two years, a constitution that centered around the institution of a weakened monarchy. In a single night, the king had thrown this constitution, as well as all the achievements of the Revolution, into jeopardy. The Assembly, therefore, had to salvage the king's reputation from this public relations nightmare or risk disaster.

The Petition

Still, not everyone was convinced that constitutional monarchy was the right path for France, nor that the king could ever be trusted to act in good faith again. Paine's statement to Lafayette, that they should just let the king go, raised an interesting question: did France even need a king? After all, during the few days that he was on the run, government continued to function as if nothing had happened. The notion of a French Republic had been a fringe idea during the entirety of the Revolution thus far, usually only discussed in casual café conversations and almost never seriously. According to the mainstream train of thought, such an institution was acceptable for a relatively small, new society such as the United States, but was unthinkable for the most populous European power, a society over a thousand years old.

After Varennes, republicanism was still a minority opinion, but it was no longer quite as taboo. The previously unknown political club, the Social Circle, was able to gather a crowd of 4,000 people to swamp a meeting of the Jacobins, to demand that they take up the call for a republic. The Jacobin Club, by far the largest of the revolutionary political clubs, was yet to go that far, though some of their number still wished to see the king punished in some way. Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794), who had recently risen from obscurity to prominence amongst the Jacobins, gave a speech in which he accused both the king and the National Assembly of treachery, yet refrained from offering up ideas of what should be done, advocating instead to leave that decision to the people. Others, such as Louis-Marie Stanislas Fréron, were less ambiguous; after attending a play depicting the legendary establishment of the Roman Republic by Lucius Junius Brutus (6th century BCE), Fréron allegedly exclaimed, "Frenchmen, why is there no Brutus among you?" (Schama, 564).

Eventually, the Assembly decided to punish the king by suspending his remaining powers until the constitution was completed. Of course, this was but a slap on the wrist and not enough for many people. The Cordeliers Club, a populist political club founded and led by Georges Danton (1759-1794), particularly wished to see different measures taken. In the days after Varennes, members of the club drafted a petition in which they demanded the National Assembly remove the king or, failing that, allow the future of the monarchy to be put to a national referendum. Backed by influential figures such as Danton, Jacques-Pierre Brissot, and even Thomas Paine, the Cordeliers declared that, by fleeing Paris, the king had effectually abdicated, and that it was the responsibility of the people to choose their own form of government. It was, in the words of historian William Doyle, essentially a republican manifesto (154).

The Cordeliers took their petition first to the Jacobins, hoping to gain their endorsement. The most radical Jacobins happily gave their approval, but it proved too much for most of the members. Led by Antoine Barnave, Alexandre de Lameth, and Lafayette, the majority of the Jacobins' active members protested their colleagues' acceptance of the petition by renouncing their membership to the club. Robespierre, whose power base lay in his command of the Jacobins, panicked, and tried to get the Jacobins who had embraced the petition to withdraw their support. However, it was too late; the former Jacobins took up residence in the old convent of the Feuillants, declaring themselves as an alternative club to the Jacobins and the Cordeliers. Although this was meant to weaken the Jacobins, it effectually radicalized them further, since those who had not left the club were the most extreme.

As constitutional monarchists, the Feuillants condemned the Cordeliers' petition. On 15 July, the day after the second anniversary of the Bastille, Barnave gave an impassioned speech in which he warned that any drastic change to the constitution would be dangerous and that prolonging the Revolution would lead to calamity. It was time, argued Barnave, for the Assembly to finally pass the constitution and bring the Revolution to an end. Yet, the Cordeliers were still determined to push through with their petition. In an announcement made in their newspaper, the Bouche de fer (Iron Mouth), they proclaimed that there would be a gathering on 17 July on the Champ de Mars, which at the time was an open field reserved for military drills. This gathering was a blatant slap in the face to the ancient French monarchy and those who supported it; it would end, of course, in bloodshed.

"Evil Conspirators"

The demonstration was to be held on the "altar of the fatherland", which had been set up for the celebration of the Bastille's fall. On the morning of 17 July, a crowd of signatories was led to the spot by Danton and the journalist Camille Desmoulins (1760-94), another Cordeliers leader who had helped instigate the Storming of the Bastille almost exactly two years earlier. Two disheveled men were found sleeping underneath the altar; suspected of treacherous intentions, such as being royalist spies, these unfortunate men were quickly lynched by the excited crowd. It should be noted that most of the demonstrators had nothing to do with these murders, as the lynchings occurred early in the morning before most of the crowd had arrived. Before long, however, over 50,000 people were gathered on the Champ de Mars. Many of them were from the poorer sections of Paris, who would have been the most affected by the recent bouts of food scarcities and unemployment; many, likely, were illiterate.

When word of this gathering reached Lafayette, the general immediately took action. Since 15 July 1789, when he had first been given command of the National Guard, he had taken his position quite seriously; it was his sacred duty to defend the law, the constitution, and the newly gained liberties of his countrymen. In the chaos that erupted in the wake of the Bastille, Lafayette clamped down on street violence in his attempt to restore order. Ever since, he had been acutely aware of the fragile thread on which peace in Paris was hanging; on 28 February 1791, afterwards called the Day of Daggers, he was in the suburbs of Paris quelling a riot when he received word of hundreds of nobles, armed with daggers, descending on the Tuileries Palace. Fearing a plot to kidnap the king, Lafayette rushed back just in time to disarm and disband the nobles. Incidents like this caused him to write to a friend, "I reign in Paris, but I reign over an angry population aroused by evil conspirators" (Unger, 239).

Such "evil conspirators" were the same men who were now instigating this upheaval on the Champ de Mars, the spot where, the year before, Lafayette himself had led 300,000 citizens in an oath of loyalty to the "nation, the law, and the king." They had attacked him personally; in the days following Varennes, Danton had given a speech on the Assembly floor, accusing the general of failing in his duty to safeguard the king:

And you, Monsieur Lafayette, you who have recently guaranteed the person of the king in this assembly on pain of losing your head, are you here to pay your debt? You swore that the king would not leave. Either you sold out your country or you are stupid for having made a promise for a person you could not trust…Do you really want to be great? Become a simple citizen again and stop 'helping' the French people. (Unger, 273)

The Cordeliers had distributed thousands of copies of Danton's speech, while the firebrand journalist Jean-Paul Marat had called for the general's head. Not long after, the National Guard broke up a mob that had been marching in the direction of Lafayette's home, carrying sharpened pikes. All of this, along with the heavy burden of his position, would have been weighing on Lafayette's shoulders as he met with Paris' mayor, Jean Sylvain Bailly. He pressed Bailly to institute martial law, citing the demonstrators' killings of the two men on the Champ de Mars as justification. Bailly, who had been hesitant to take such measures before, now agreed, placing the city under martial law. It would prove a fatal decision, one that would eventually cost Lafayette his career, and Bailly his head. Neither man would have known this, of course, as Lafayette mounted his white horse and personally led his men to the Champ de Mars.

Massacre

The National Guard soon arrived amongst the demonstrators, clearly as unwanted guests. A year before, Lafayette's appearance at this exact spot inspired cheers during the Festival of the Federation. Now, it received only grave silence and hostile stares. The National Guardsmen carried the red warning flag, a clear indication that the demonstrators had better disperse or face the consequences. Bailly himself arrived with additional troops, and tensions rose. Far from scattering, the crowd instead met the soldiers first with jeers and insults, then with volleys of stones. Although mostly unarmed, a few shots rang out from the crowd, missing Lafayette but hitting a dragoon. The National Guard returned fire.

Men, women, and children crumpled to the ground as the Guard charged in. The air would have been filled with thick smoke and terrified shrieks as 50,000 people stumbled over one another to get away. When all was said and done, at least 13 people were dead, although some contemporary sources put the number as high as 50. Dozens more were wounded.

In the weeks that followed, Lafayette cracked down on republican and anti-monarchist activists. Around 200 of the movement's known leaders were arrested. Danton fled to England, while the journalists Desmoulins and Marat went into hiding. Even Robespierre, who had played no part in the demonstration but had condemned the National Guard and the massacre, laid low for a while. For the moment, it seemed that Bailly and Lafayette had crushed the budding republican movement in one swoop. With the Jacobins unraveling and the Cordeliers on the run, the Feuillants reigned supreme.

Aftermath

With the calls for both a republic and for the king's abdication temporarily contained, the Constituent Assembly went about completing its work. Spearheaded by Barnave, the Feuillants made last-minute amendments to the constitution to strengthen the king's position and make it more acceptable to Louis XVI. Of course, Louis XVI was far from pleased at the result but consented to it anyway when it was presented to him that September. France was now officially a constitutional monarchy, with Louis XVI as its citizen-king. Yet, it was a system that many people were unhappy with, based around a king who plotted counter-revolution behind closed doors. Needless to say, the Feuillants' flimsy success would not last for long; within a year, France would be at war with Austria and Prussia, during which time the Jacobins would rise to power. On 21 September 1792, the constitutional monarchy was abolished in favor of the First French Republic.

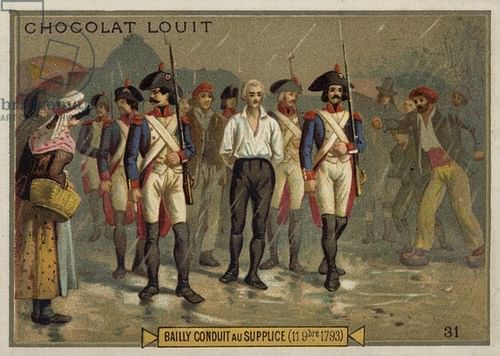

The Champ de Mars massacre, however, was neither forgotten nor forgiven by the people of Paris. A year before, Lafayette and Bailly had both been adored as champions of the Revolution. Now, the events of 17 July were dark stains on their reputations that would never fully be washed away. No longer seen as the daring hero who had risked everything to fight for freedom in the American Revolutionary War, Lafayette was now looked upon with distrust by the people and would later become a popular target for the inflammatory speeches of Robespierre and Danton. Although Lafayette was given command of an army in 1792, the Jacobins' pressure would cause him to flee France, leading to his arrest in the Austrian Netherlands while trying to book passage to the United States. He would spend most of the rest of the Revolution in an Austrian prison. Bailly, meanwhile, was not so lucky. Having resigned the mayorship in November 1791, he moved to Nantes but was later recognized and imprisoned. On 12 November 1793, he was guillotined, primarily for his role in the massacre; he was executed on the Champ de Mars.

Together with the Flight to Varennes, the Camp de Mars Massacre marked a turning point in the French Revolution. Panicked by the king's betrayal, the people began to question the usefulness of the forthcoming constitution in protecting their rights. These doubts only would have been amplified when soldiers of the National Guard, ostensibly there to protect them, mowed down unarmed citizens on the orders of men they admired. The massacre, therefore, had the effect of completing what Varennes had started, shifting the tide of public opinion away from the king and his allies. Whereas many had previously seen an end to the Revolution in sight, there was no going back now. The Revolution still had a long way to go, with its darkest days still ahead.