Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) was a Stuart king who, like his father James I of England (r. 1603-1625), viewed himself as a monarch with absolute power and a divine right to rule. His lack of compromise with Parliament led to the English Civil Wars (1642-51), his execution, and the abolition of the monarchy in 1649.

King Charles grew tired of wrangles with Parliament over money and so decided to do without that institution for eleven years. Then between 1640 and 1642, Charles was obliged to call Parliament to raise cash for his campaigns against a Scottish army, which had occupied northern England, and a full-blown rebellion in Ireland, both fuelled by religious differences and the king’s high-handed policies. Parliament attempted to guarantee its own future, and when the king broke his promises of reform, war broke out. The English Civil War was largely fought between ‘Roundheads’ (Parliamentarians) and ‘Cavaliers’ (Royalists) in over 600 battles and sieges in England alone. Ultimately, the professional New Model Army won the day for Parliament and Charles I was tried and found guilty of treason to his own people and government. The king was executed on 30 January 1649. Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658) ruled the ‘commonwealth’ republic as Lord Protector, but his death was soon followed by the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. The new king was Charles’ son, Charles II of England (r. 1660–1685).

Family & Early Life

Charles was born on 19 November 1600 in Dunfermline Palace, Scotland. His father was James I of England (who was also James VI of Scotland, r. 1567-1625), and his mother was Anne of Denmark (l. 1574-1619), the daughter of Frederick II of Denmark and Norway (r. 1559-1588). Charles’ grandmother was Mary, Queen of Scots (r. 1542-1567). James I was of the royal Stuart line, and he had unified the thrones of Scotland and England after Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603) left no heir. Charles was the second son of King James, but his elder brother Henry died of typhoid fever in 1612 and so he became the heir apparent. Charles’ elder sister Elizabeth (b. 1596) married the King of Bohemia, and her grandson would rule England as George I of England (r. 1714-1727), the first of the Hanoverian Dynasty.

Charles did not enjoy robust health as a child, he was shy - perhaps because of his stammer, and he always came second-best when compared to his more favoured brother Henry. Reaching maturity, Charles spent a lot of time with King James’ hated courtier George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham. The duke was seen as a talentless social upstart who had enjoyed a meteoric rise only thanks to the king’s infatuation with him.

In 1624 it was arranged for Charles to marry Henrietta Maria (1609-1669), the young sister of Louis XIII of France (1610-1643). The French royal obviously did not mind the small stature of her betrothed - a mere 1.6 metres tall (5ft 4 in) or his reputation for being rather stubborn, dull-witted, and a complete stranger to a sense of humour. The couple went on to have nine children, the two eldest sons being Charles (b. 1630) and James (b. 1633), both of whom would one day become king.

Succession

Charles inherited the crown when his father died of illness on 27 March 1625. He was now the king of England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. James I had run into problems with Parliament over his high spending, and relations with the English nobility were not helped by the king’s favouring Scotsmen and ill-chosen advisors like Villiers. Charles proved to be even more sure of his divine right to rule than his father. That his troublesome reign was ill-fated was indicated by three odd occurrences at his coronation on 2 February 1626 in Westminster Abbey: the dove on his royal sceptre snapped off, the gem in his coronation ring fell out, and there was an earthquake.

There were more concrete and disheartening episodes to follow such as bad military defeats to both the Spanish and French. An attack on Cadiz in mid-1626 was a humiliating disaster, and an attack on La Rochelle in June 1628 was equally unsuccessful. Both military defeats had been masterminded by the Duke of Buckingham, by now the singularly most hated individual in England. Villiers was killed by an assassin outside a public house in August 1628 much to Parliament’s delight. Peace with France was signed in 1629 and with Spain in 1630.

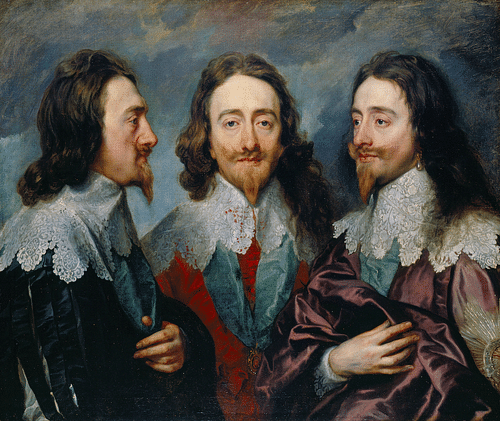

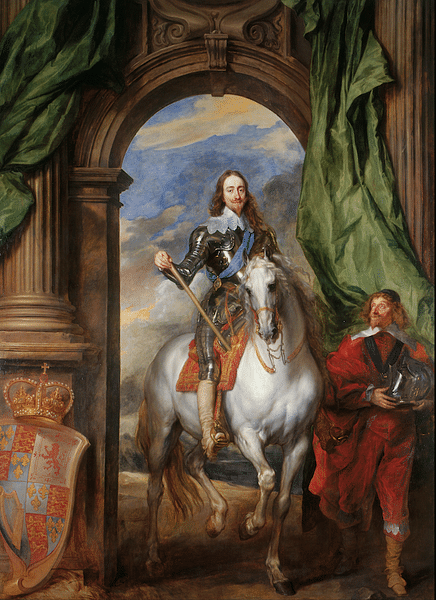

Regarding more peaceful pursuits, Charles was a keen student of art and he bought a collection of ‘cartoons’ (drawings) by Raphael (1483-1520). The king appointed Anthony van Dyck (1599-1641) as his court artist from 1632, and a famous work he produced is the c. 1635 triple portrait with three different views of Charles (Queen’s Drawing Room, Windsor Castle). Other favoured artists included Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506), Titian (c. 1487-1576), and Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), as the king spent heavily on accumulating a formidable collection of paintings. Many of these works are now in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Charles’ other cultural interests included chess, tennis, and hunting, as well as attending plays and masques.

Clashes with Parliament

Charles' royal policies meant that he frequently clashed with Parliament over finances since that body was responsible for passing new tax laws and deciding matters of budget. Charles thought he could well do without a parliament and rule as an absolute monarch, like his counterpart in France, with a divine and unquestionable right to rule. Compromise and concession were not in the king’s nature, and this deficiency, above all others, would be his undoing. The English king once stated:

Parliaments are altogether in my power…As I find the fruits of them good or evil, they are to continue or not to be.

(McDowall, 88).

Accordingly, Charles repeatedly dismissed and then recalled Parliament. Charles even attempted to bypass the institution altogether by acquiring money by other means. Cash was extracted from merchants and bankers, customs duties were increased, and archaic forest laws revived (even in areas where the forests had long since disappeared) so that fines could be applied to fill the royal coffers. Charles also widened the Ship Money, a tax originally designed to fund the navy and applied only to coastal areas but now extracted from inland communities, too.

Aside from these new financial burdens, the king miscalculated badly when he thought that the English elite would give up their hard-won rights to participate in the governance of the country. As it happened, the king could not find sufficient funds from private sources, and in 1628 he was obliged to make concessions to Parliament such as only raising money via Acts of Parliament and not imprisoning his subjects without legal justification. Collectively, these new rights of Parliament were known as the Petition of Right.

However, Charles had a rethink and decided to dissolve Parliament in March 1629. For a few years, the king seemed to have been right in his claim that Parliament was unnecessary. The annual budgets were balanced and there was even a reduction in corruption within the government. Then in 1637 things began to go wrong, especially concerning his religious policy. Charles had appointed William Laud as the Archbishop of Canterbury, head of the Church of England, in 1633. Laud was detested by the Puritans who remained a rich and powerful section of English society who had had a strong presence in Parliament. Laud further outraged the Puritans when he reintroduced certain Catholic practices into the Anglican Church. Laud also upset Scottish church leaders by trying to install bishops and by introducing a new prayer book in 1637. Far from being a problem of ecclesiastical debate, these issues boiled over onto the battlefield in what became known as the Bishops’ Wars.

A Scottish army took the field against the king, crossing the border into England in 1638 and again in 1640, occupying Newcastle, vital for its coal. The absence of Parliament now proved crucial and the king could only muster an army of inexperienced militia troops to meet the threat. The two forces met but Charles, realising his poorly-trained army was likely to lose the day, decided to concede to Scottish demands. Scotland was permitted its religious freedom, and the leaders on the battlefield were promised a handsome sum in cash to stand down. The king then had the practical problem of where exactly to get this money from without Parliament, the body which would normally have acted to raise it. Without much choice in the matter, Parliament was recalled in spring 1640, the first time in eleven years. A three-week wrangling achieved nothing, and then a second defeat to a Scottish army required the king to call another Parliament in November. These two Parliaments were respectively known as the Short and the Long Parliament, and their names give some indication of the breakdown of government between the monarch and Commons.

The Members of Parliament seized their opportunity with the Long Parliament and the king’s military predicaments to guarantee their future survival. Money would be raised for another army but only on the condition that a law was passed which meant a Parliament must be called at least once every three years, that it could not be dissolved by the monarch’s wishes alone, and royal ministers now had to be approved by Parliament. The king agreed but then Charles blithely ignored his promises. The consequence was a civil war, or rather a series of them often called the Wars of the Three Kingdoms since Ireland and Scotland were involved too.

Civil War

In 1641 a major rebellion broke out against English rule in Ireland, fuelled by grievances over English land confiscation and the exclusive employment of English and Scottish immigrants on many large estates. Ulster was a particularly bloody battleground while Charles and the English Parliament wrangled over the formation of an army necessary to quell the rebellion. The latter was anxious that the king use such a force in Ireland and not against themselves. These fears were perhaps not unfounded and the king’s attempted arrest of five Members of Parliament in January 1642 hardly instilled confidence. The group, who included one John Pym, had written the Grand Remonstrance listing the king’s abuses of power and which was passed by Parliament in November 1641. In retaliation for the arrests, the Parliamentarians locked the gates of London, preventing Charles from entering his own capital. The king relocated to Nottingham, but he was far from satisfied. A royal army was formed, and the fighting stage of the English Civil Wars began in November 1642, the so-called First English Civil War (1642-6).

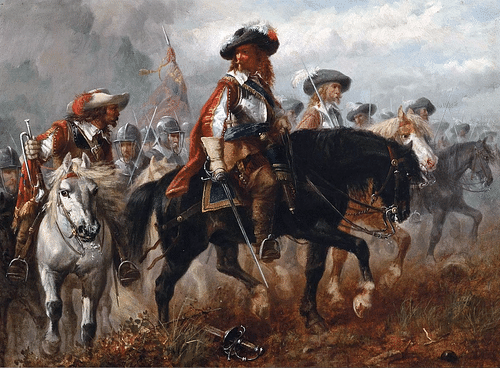

Although the vast majority of people did not particularly care about the matter, large swathes of the country were controlled by one side or the other. The two sides were called the Royalists or ‘Cavaliers’ and the Parliamentarians or ‘Roundheads’ (because the first troops were London apprentices who had short hair). The western and northern parts of England remained loyal to the king with the exception of a handful of isolated centres which included Gloucester, Plymouth, and Hull. These cities, London and the southeast quarter of England were controlled by Parliament. In terms of people, the king had the support of the House of Lords and some Members of Parliament. The Parliamentarians had control of the navy and the merchant class. This meant the king was very limited in his ability to pay his army, a situation which led to significant desertions and unpopular looting raids by the ‘Cavaliers’. The opposition, meanwhile, was able to call Parliament and raise taxes to pay for their army; not a popular move with ordinary people but a big advantage in the war.

The Royalists won the first major battle at Edgehill in Warwickshire on 23 October 1642, but the war became one of indecisive engagements and lengthy sieges. Half of the large-scale battles ever to be fought on English soil occurred during this bloody decade of civil war. Neither was the carnage restricted to the military; it is estimated one in ten people in urban areas lost their homes. Even for those who escaped direct action, taxes were crippling, there was a slump in trade, and on top of everything, there was a run of bad harvests. Both sides used conscripts in their army, but the Parliamentarians had the advantage of a gifted commander, one Oliver Cromwell. A country gentleman, Cromwell turned out to be a visionary military leader who believed in the importance of a well-trained army. This he formed and called the New Model Army. A further advantage was that Charles’ use of Irish Catholic troops alienated the king from his own subjects. The Crown was about to take a tumble and the king’s head with it.

Execution

The Parliamentarians, with the help of Scottish troops, won the battle of Marston Moor near York on 2 July 1644. At the Battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire on 14 June 1645 Charles led his army against the Parliamentarians led by General Fairfax. Oliver Cromwell commanded the army’s right wing. The Parliamentarians won the day, and the king fled in disguise to find safety in the arms of a Scottish army in the north of England. It was a temporary evasion as the Scots would not harbour a monarch who did not favour Presbyterianism or being accountable to the people.

After lengthy political negotiations which included a change of heart by the Scots, Charles was handed over to the English in January 1647 and so was taken prisoner in his own kingdom. The king’s prison was not a bad one: house arrest at Hampton Court Palace. On 11 November 1647, the king made an escape and managed to reach the Isle of Wight where he spent the next year in effective exile in Carisbrooke Castle. On 1 December 1648, a force of Parliamentary officers was finally sent to the island, and they took the king to Hurst Castle. Charles had unwisely encouraged the Royalists to fight on, and a Scottish army was raised to come to his aid, but this was defeated at the battle of Preston in 1648 during the so-called Second English Civil War (Feb-Aug 1648).

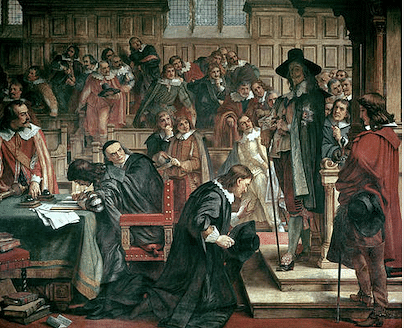

The burning question was what to do with a deposed king. The majority of Parliament and the people wanted to reinstate Charles but permanently reduce his powers while a number of extremist Puritans were calling for Charles’ execution. In the end, might was right, and the moderate Members of Parliament were removed, leaving Parliament with only 53 of the more extreme Parliamentarians. Charles was put on trial on 20 January 1649 and found guilty of tyranny, treason, and making war on his own people. Charles made no defence since he did not consider the court to have any authority over him:

I would know by what power I am called hither…I would know by what authority, I mean lawful…Remember, I am your king, your lawful king…a king cannot be tried by any superior jurisdiction on earth.

(Ralph Lewis, 160)

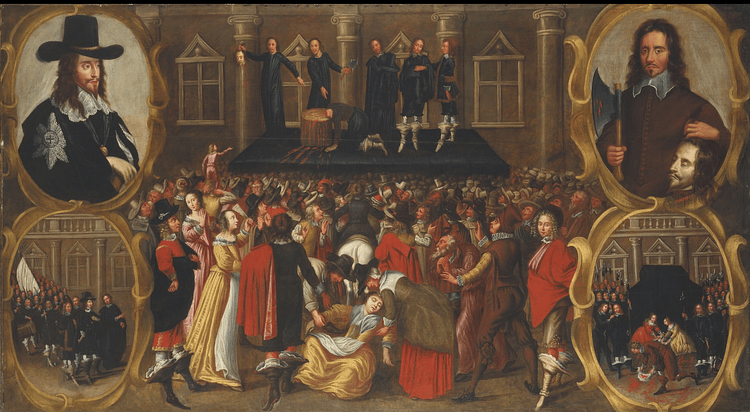

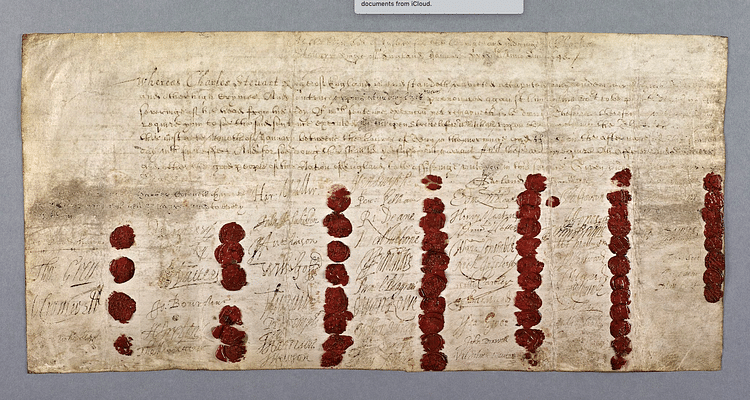

The king, called merely Charles Stuart before the court, was sentenced to death by beheading. The document, carrying the seals of the court commissioners involved, survives today and shows that only 59 of the 159 dared to put their seal to it. Charles I was executed on 30 January 1649. The king had met his fate with dignity, even wearing two shirts so that he would not shiver in the cold January air and the crowd think that he trembled with fear: "The season is so sharp as probably may make shake, which some observers may imagine proceeds from fear" (Ibid). Then, appearing before the crowd on the scaffold, Charles proclaimed:

I must tell you that the liberty and freedom [of the people] consists in having of Government, those laws by which their life and their goods may be most their own. It is not for having share in Government, that is nothing pertaining to them. A subject and sovereign are clean different things.

(Ibid)

Charles I was forbidden a state funeral, and he was quietly buried in Saint George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle.

From Cromwell to the Restoration

The country became a republic, the title and office of the monarchy was abolished (but not in Scotland), the House of Lords was abolished, the Anglican Church was reformed, and even the British Crown Jewels were broken up and sold off. Scotland remained loyal to the crown, and Charles I’s eldest son Charles was, by right of birth, its king. However, a Scottish army was again defeated by an English one in the so-called Third English Civil War (1650-1), and the would-be Charles II of Britain was obliged to flee to France.

The English Civil Wars were finally over but the Parliamentarians were now split as some wanted radical reforms and others objected to the undue influence of Cromwell’s army. Disagreements led to Parliament being dissolved in 1653. Oliver Cromwell was then made Lord Protector but his authoritarian rule, much more so than Charles’ had ever been, made many wish for the moderation and tradition of the old monarchy. Not least of Cromwell’s popularity gaffes was his decision to abolish both Christmas and Easter and to prohibit the playing of games on a Sunday. Life in Britain was not quite as much fun as it had been. When Cromwell died in 1658, his republic died with him. Ironically for a republican, Cromwell’s chosen successor was his son Richard Cromwell, but he did not enjoy universal support. Following a march on London in 1660 and with the support of the army, the monarchy was restored, and all Cromwell’s Acts of Parliament were cancelled. In the same year, Charles I was declared a martyr by Parliament and made a saint by the Anglican Church. Charles I’s son became Charles II, and the Stuarts went on to rule Britain until 1714 when they were succeeded by the House of Hanover.