Captain Charles Vane was an English pirate active in the Caribbean and off the east coast of North America between 1716 and 1720. The pirate, who infamously refused a pardon and instead fired his cannons at the ship of Governor Woodes Rogers in the Bahamas, was eventually captured, found guilty of piracy, and hanged in Jamaica in March 1721.

Charles Vane was a relatively successful pirate, capturing merchant vessels and looting their cargoes from Hispaniola to New York. These attacks were noted for their cruel treatment of captured seamen. Less successful was his grip on his own crew. Vane’s second-in-command once sailed off with a captured ship and then his crew mutinied and replaced him with 'Calico Jack' Rackham. Vane was later shipwrecked on a desert island and when finally rescued he was handed over to the authorities who were keen to make an example of one of the most wanted men in the Caribbean.

Early Career

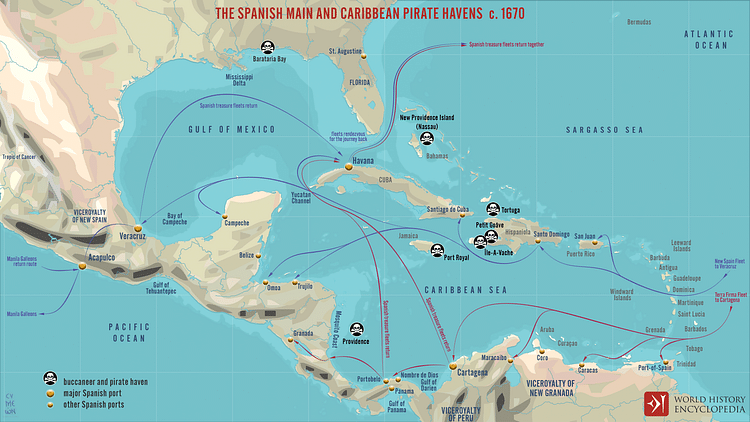

Charles Vane first turned to piracy in 1716 when he joined the crew of the English pirate Henry Jennings who was then based in Jamaica and New Providence (now Nassau) in the Bahamas. Jennings and Vane also made retrieving silver from sunken Spanish galleons in the gulf of Florida something of a specialty, much to the annoyance of the Spanish Crown, which had sent its own salvage crews for that purpose.

In May 1718, one crew member of a captured ship escaped to testify against Vane to Governor Bennett of Bermuda. Called Nathaniel Catling, the mariner had been aboard the Bermudan sloop Diamond when Vane’s pirate crew attacked it in the Bahamas. Catling reported that he and all of his fellow crew had been beaten up and the ship looted and then burned. Catling had been hanged by the pirates and hacked at with a cutlass but miraculously survived his ordeal.

Within a week, Catling’s tale was repeated with even worse additions by another seaman who had escaped the clutches of Vane and his crew. One Edward North, captain of another Bermudan sloop, this time the William and Martha, testified to Governor Bennett that he, too, had been attacked, beaten, and robbed. North also recorded that one of his crew had suffered the ignominy of being tied to the ship’s bowsprit and then tortured with burning matches to reveal the location of the ship’s valuables.

Escape From New Providence

In August 1718, Vane made his first independent pirate raid and captured a French merchant vessel. Meanwhile, the new governor of the Bahamas, Woodes Rogers (d. 1732), was just arriving at New Providence having been charged with the task of clearing out the notorious pirate den. Unlike his comrade Henry Jennings, Vane had no intention of accepting the pardon Rogers was offering all pirates as this would have meant giving up his recently acquired plunder. Vane was happy enough to keep on pirating and so he escaped New Providence in the fast sloop Ranger, audaciously sending his French capture as a fireship towards the governor’s vessel and firing a cannon shot as he passed for good measure. Vane’s escapade even became news in London, featuring in the press in December.

Within two days, Vane captured a bigger sloop and a few weeks later he stepped up again, this time to a slave ship brigantine captured off the Carolinas. The brigantine was renamed Ranger and boasted 12 cannons and a crew of around 80-90 men; the sloop was given to a second-in-command, Yeats. On his rampage of crime, Vane boldly flew two flags: the English flag and a black pirate flag, but this split loyalty was reflected in Vane’s own crew for Yeats soon decided to sail off on his own, slipping away from Vane in the night. Vane sailed in pursuit, caught up with Yeats, and fired a broadside at his sloop but then let him go, despite having a faster ship. The ultimate fate of Yeats is not noted in any historical records.

The East Coast of America

The authorities pursued Vane, but his crew and ship were too fast. As one naval officer noted: "our sloops gave over the chase, finding he outsailed them two foot for their one" (Konstam, The Pirate Ship, 7). By September 1718, another force, this time sent by Governor Spotswood of Virginia, was in hot pursuit of Vane. This fleet did not manage to capture Vane, but they did assist in the search for another notorious pirate, Stede Bonnet, who was captured and hanged shortly after.

Captain Vane visited Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, in October 1718, spending some time at his pirate base on Ocracoke Island, North Carolina. The two pirate crews were said to have enjoyed a week-long party at what was the largest pirate gathering ever to occur in North American waters. Vain then sailed as far north as New York, plundering ships along the way, including two off Long Island. The pirate then turned back to the Caribbean, where he raided ships sailing through the Bahamas. Vane had by now built up quite a pirate fleet and haul of booty, but his return to the Caribbean would soon turn sour.

Mutiny, Shipwreck & Capture

Vane was known as a cruel pirate captain, dishing out punishments such as keelhauling, which involved tying a person with rope, throwing them overboard, and then dragging them either under the ship from one side to the other or along the entire length of the ship. More seriously for his captaincy, Vane faced accusations of not sharing out his plunder fairly. There might not have been all that much honour amongst thieves but one point on which pirates were sticklers for the rules was the distribution of booty.

On a charge of cowardice based on their leader’s reluctance to attack a well-armed French frigate in the Windward Passage between Cuba and Hispaniola, Vane was relieved of his captaincy in November 1718 by his crew. The mutineers then promoted John Rackham to the role of leader. Otherwise known as 'Calico Jack', Rackham had been Vane’s quartermaster and second-in-command, captaining the captured English vessel Kingston. It may have been that the quarrel was not about cowardice but really because Rackham did not want to share the Kingston’s cargo of liquor. Now independent, Rackham famously acquired the women pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read for his crew, but he was not any more successful than his predecessor; all three were captured by the Jamaican authorities in 1720.

Meanwhile, Vane had been sent off in a small brigantine with a handful of men to sail it, but things went from bad to worse when a hurricane broke up the ship in the Bay of Honduras and deposited Vane and one other survivor on Baracho Island. The pair were kept alive thanks to some passing turtle fishermen. Fortunately for Vane, a ship stopped by the usually uninhabited island and spotted the marooned pirates. Unfortunately, the captain of the passing ship was Holford, a captain of a ship Vane had previously tried to take over, and when he identified Vane, he simply sailed on. Vane was rescued by another ship, but then he met Holford again, and it was not a case of third time lucky. Holford put Vane in chains and handed him over to the authorities in Port Royal, Jamaica. There Vane was tried for piracy by a Vice-Admiralty court and found guilty in March 1720. After a year in prison, Vane was finally hanged in March 1721. Like Captain Kidd almost 20 years before, Vane’s corpse was hung to slowly rot in a cage on the islet of Gun Cay as a stark and public warning to others of the perils of piracy.

In the celebrated pirate who’s who, A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates, compiled in the 1720s by Captain Charles Johnson or possibly Daniel Defoe, Vane has his own chapter. The author describes Vane as being cowardly at his execution and, although suffering agonies, being wholly unrepentant of his life of piracy.