Charon is a figure from Greek mythology where he is the boatman who ferries the souls of the dead across the waters of Hades to the judgement which will determine their final resting place. The Greeks believed the dead needed a coin to pay Charon for his service and so one was placed in the mouth of the deceased.

Charon was a popular subject on 5th-4th century BCE Greek pottery scenes, especially the lekythoi used to store fine oils and perfumes which were commonly buried with the dead. Charu was a similar figure in Etruscan mythology, although there he often carries a hammer. Charon continued to feature in Roman mythology and he enjoyed a revival with other classical ideas during the Renaissance (1400-1600). The largest moon of the dwarf planet Pluto is named after Charon.

The Boatman of Hades

The Greek Charon as the boatman of the dead is an idea which may well have been influenced by Mesopotamian and Egyptian mythology, where there, too, the Underworld contains rivers which hinder the progress of the soul. In Greek mythology, Charon is the son of Erebus (Darkness) and Nyx (Night). His name may have originally meant ‘fierce brightness’.

Charon’s job was to transport the shades or souls of the dead across either a river - most typically named as the Acheron and, in later sources, the poisonous Styx - or a lake, often called Acherousia. The destination was Hades, which was the Greek underworld (and also the name of the god who ruled there), or, more precisely, the inner part of that realm. Often accompanying Charon is the messenger god Hermes, who was thought to act as a guide to the dead in Hades. Often Hermes escorts the soul to Charon, who then takes them deeper into the underworld for judgement.

Hades is described in Greek literature as a cold, dark, damp, and mirthless place, which it is everyone’s fate to end up, that is until post-5th century BCE writers created an alternative destination for good souls. Accordingly, from Hades, good souls went to the Elysian Fields and forgot all their troubles and bad souls went down to Tartarus in the deepest depths of Hades. Those souls who had wronged the gods fared even worse and were given wicked and eternal punishments like Sisyphus who had to endlessly roll a boulder up a slope.

In many Greek accounts, Charon assists heroes who descend into Hades on various challenges, such as Odysseus, Orpheus, and Psyche. Hercules engaged Charon’s services when, for his twelfth and most difficult labour, he was required to fetch the terrible three-headed dog Cerberus (aka Kerberos). This terrible hound made sure nobody ever left Hades or crossed the waters without either Charon or Hermes as their guide. Charon was punished by Hades for allowing the living Hercules into the realm of the dead. The boatman was shackled for one year, which must have left quite a queue of expectant souls waiting on the shores of Acheron.

In order to ensure Charon did actually bother to take one to Hades in his boat, Greeks buried the dead with a small coin in the mouth as it was thought this money could then be useful to pay the boatman. The coin was typically an obol and was placed under the tongue. Those souls without the coin were obliged to wait on the shores for 100 years before Charon would condescend to take them across for free. A proper burial was also considered essential to allow the soul to reach Charon’s boat. In later periods, the money tradition changed to placing a coin over each eye of the deceased before burial.

Etruscan Charu

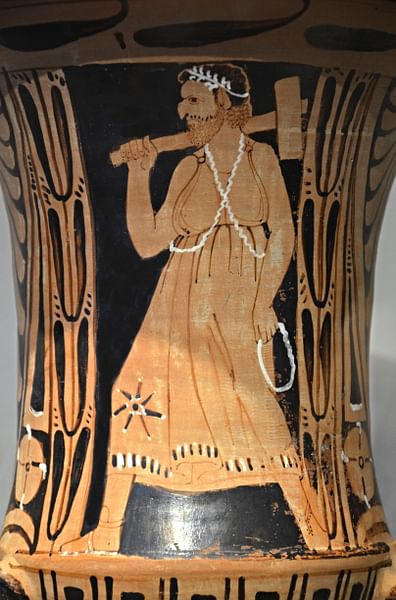

In other versions of the myths, Charon is not a ferryman but Death itself. The Etruscans in central Italy (8th-3rd century BCE) had a very similar figure to this version, although there are some differences. Etruscan Charu (or Charun) is also a ferryman for the dead, but in Etruscan art, he carries a hammer or torch, and he frequently has a hooked nose. The hammer may have been to break down the door of the tomb (a view supported by the proximity of depictions of Charu near the entrance) or to break the gates of Hades to allow the soul to enter. The Etruscans seem to have viewed Charu as some sort of terrible demon of death as in art he frequently has an ugly face, animal ears, and wings. Etruscan Charu was one of several demons with the same role, and Charu himself may have had several aspects.

Charon in Ancient Art & Literature

Charon first appears in Greek literature in the epic poem Minyas (fr. 1), which perhaps dates to the 6th century BCE. He features in several plays of ancient Greek theatre, notably the 405 BCE Frogs, a Greek comedy play by Aristophanes (c. 460 - c. 380 BCE), where Dionysos visits Hades to judge a poetry competition. The figure continued to be popular in the Roman period and appears, for example, in Book VI of the Aeneid by Virgil (70-19 BCE) and in the dialogues of Lucian (c. 125-180 CE). Virgil describes Charon as having blazing eyes, and this description proved a popular one with later authors and artists.

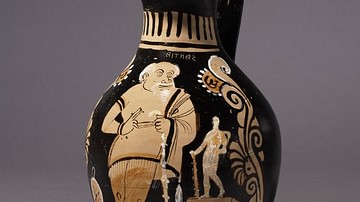

The earliest known visual representations of Charon appear on Greek black-figure pottery dating to around 500 BCE. The figure of Charon remained popular on many types of greek pottery, particularly vessels buried with the dead such as the lekythoi (sing.: lekythos). Lekythoi were tall, single-handled flasks used to store fine oil or perfume, and Charon is a common subject on them from around 470 BCE onwards. A fine example of the latter with a typical white-slip background to the scene dates to c. 450 BCE and is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Made in Attica, the vessel shows Charon wearing a rough tunic over one shoulder while he stands in the prow of his boat with a pole in his hand. Next to him is Hermes holding his herald’s staff or kerykeion.

Charon often wears a brimless cap like a labourer’s, but sometimes he is shown with white hair; he might often be propelling his boat using a long pole or steering oar. He may be represented as an old man or a younger man with a beard. His boat frequently has an eye painted on the prow, which was believed to ward off evil spirits. Besides pottery, Charon appeared in a celebrated series of wall paintings in the Hall of the Knidians at Delphi by the 5th century BCE artist Polygnotus. In Etruscan art, Charon/Charu/Charun appears frequently on wall paintings in tombs, on funerary urns, and on sarcophagi.

Legacy

Charon, sometimes now better-known as Charos, continued to be a figure of importance in medieval minds and he appeared in many works of Renaissance art and medieval literature. Charon features in the Inferno section of the Divine Comedy (c. 1319) written by Dante Alighieri (1265-1321). More recently, Charon is the origin of the Charontas figure in Greek folklore, a sort of angel of death who some people believe appears just before a person dies. Finally, the largest moon of the dwarf planet Pluto has been named after Charon, an entirely appropriate pairing since Pluto was, in many respects, the Roman equivalent of Hades.