Chichen Itza, located at the northern tip of the Yucatán Peninsula of modern Mexico, was a Maya city which was later significantly influenced by the Toltec civilization. Flourishing between c. 750 and 1200 CE, the site is rich in monumental architecture and sculpture which promote themes of militarism and displays imagery of jaguars, eagles, and feathered-serpents. Probably a capital city ruling over a confederacy of neighbouring states, Chichen Itza was one of the great Mesoamerican cities and remains today one of the most popular tourist sites in Mexico. Chichen Itza is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Historical Overview

The name Chichen Itza probably derives from a large sinkhole known as the Sacred Cenote or 'mouth of the well of the Itza' into which the Maya threw offerings of jade and gold, and as the presence of bones testifies, human sacrifices. The early history of the site is still not clear, but settlement was certain by the Classic period (c. 250-900 CE). With the collapse of Teotihuacan, migrants may have come to the site from varying parts of Mesoamerica, and it seems likely there was contact with the Itza, a Maya group. A second period of construction seems to coincide with influence from the Toltec civilization. That Chichen Itza was a thriving trade centre with a port at Isla Cerritos is evidenced by finds of goods from elsewhere in Mesoamerica, for example, turquoise from the north, gold disks from the south, and obsidian from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec. The cultivation of cacao is known, and the city may have controlled the lucrative salt beds on the nearby northern coast.

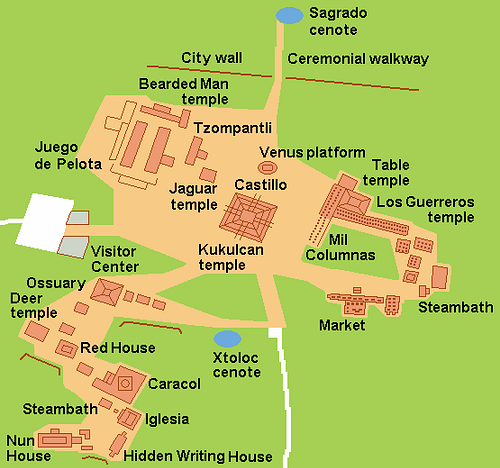

The city has been traditionally divided into two distinct parts and periods, even if there is some overlap both in time and design, and together they cover some 16 square kilometres. The earliest, in the south, is native Maya dating to the Epiclassic period (c. 800-1000 CE) with buildings displaying the distinct 'Puuc' architectural style and Maya hieroglyphs. The plan is more spread out than other parts of the city and, constructed on a roughly north-south axis, may reflect the course of the Xtoloc Cenote water source.

The second part of the city has been traditionally dated to 1000-1200 CE and is more mysterious, creating one of the most contentious debates in Mesoamerican archaeology. Built in the Florescent style and along a more ordered plan, it displays many hallmarks of the Toltec civilization, leading scholars to believe that they either conquered Chichen Itza as they expanded their empire from their capital Tula over 1,000 km away, or there was some sort of cultural and trade sharing between the two centres. Common features between the two cities found in architecture and relief sculpture include warrior columns, quetzal-feathered rattlesnakes, the clothing of subjects, chacmools (sacrificial basins in the form of a reclining person), atlantides (support columns in the form of standing males), the representation of certain animals, a tzompantli (sacrificial skull rack), Tlaloc (the rain god) incense burners, and personal names represented by glyphs which are present at both sites but which are not Maya.

Alternative to the two-period view, the Americas historian George Kubler divides the buildings of Chichen Itza into three distinct phases: prior to 800 CE, from 800 to 1050 CE, and 1050-1200 CE. Kubler adds that the latter stage saw the addition of ornate narrative reliefs to many of the buildings at the site. It has also been suggested that due to various styles of architecture pre-dating those found at the Toltec capital Tula, it may actually have been Chichen Itza which influenced the Toltec rather than the reverse. The exact relationship between the two cultures has yet to be ascertained for certain, and there are certainly other Mesoamerican (but non-Toltec) architectural and artistic features at Chichen Itza which are evidence of influence from other sites such as Xochicalco and El Tajin.

Chichen Itza fell into a rapid decline from 1200 CE, and Mayapán became the new capital. However, unlike many other sites, Chichen Itza never disappeared from memory, and the city continued to be revered and esteemed as a place of ancestry and pilgrimage into the Postclassic period and up to the Spanish conquest, and even beyond.

Architectural Highlights

The earlier section of Chichen Itza displays many Classic Maya traits. The Temple of the Three Lintels, for example, has Chahk masks at each corner. Other structures include two small temples built on raised platforms, known as the Red House and the House of the Deer, and a pyramid known as the High Priest's Grave, named after the discovery of a tomb within it. There is also the 7th-century CE Red House with its bloodletting frieze, the Nunnery with its carvings of the rain god Chac, and the small temple known as the Iglesia. All are Classic period structures.

The Caracol

The Caracol is one of the most impressive monuments at the site. It was constructed prior to 800 CE and was used as an astronomical observatory, especially of Venus, and perhaps was also a temple to Kukulcan in his guise as the god of the winds. A large flight of stairs on two levels leads to the circular tower structure which has windows not aligned with the steps giving the illusion the tower is turning. The interior vaulting may have been designed to represent a conch shell (an object associated with Kukulcan), and a spiral staircase gives access to the second floor. The vault is over 10 m high, the largest such Maya structure. The building as it is seen today was probably a result of remodelling to incorporate Toltec design features.

Pyramid of Kukulcan

Dominating Chichen Itza is the huge Pyramid of Kukulcan, also known as the Castillo (Castle), constructed before 1050 CE. The pyramid is 24 metres high, each side is 58-9 metres wide, and it has nine levels. On each side of the pyramid is a staircase which leads up to a single modest square structure. This summit building has two chambers and is decorated with jaguar relief panels and round shields. Each stairway climbing the pyramid has 91 steps, except the northern side which has 92, and so, adding all four together, one arrives at a significant 365. Seen from above, the cross created by the stairways imposed on top of the square pyramid base recalls the Maya sign for zero. At certain times of the year, for example on the autumnal equinox, triangular shadows from the different levels of the pyramid are cast onto the sides of the northern staircase, giving the illusion a gigantic snake is climbing the structure built in honour of the feathered-serpent god. The northern side also has large stone snakeheads to further remind the purpose of the building. Used for religious ceremonies, human sacrifices would also have been made on the top terrace. Inside the pyramid, another 9-level pyramid was built, this one with only a single staircase on the north side. Inside were a chacmool and a red jaguar throne inlaid with jade. This smaller pyramid was probably used for a royal burial, perhaps even of the great Toltec king Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl.

Temple of the Warriors

Another huge structure at Chichen Itza is the Temple of the Warriors, a three-level pyramid with neighbouring colonnades on two sides creating a semi-enclosed court. It was built in the Early Post-Classic period, sometime between 800 and 1050 CE. The colonnade of carved warrior and female gift bearer columns in front of the pyramid would have once had a roof. The building at the top of the pyramid has a doorway framed with feathered-serpents and two chambers; one contained a chacmool and the other a throne. The structure shares many common features with the Toltec Pyramid B of Tula. Buried within the base of the temple is another, older structure known as the Temple of the Chacmool. The interior walls of the temple were decorated with wall paintings showing scenes of warriors with captives, a lake, and thatched houses, all with some attempt made at achieving perspective. Next to the Temple of the Warriors is a more ruined pyramid known as the Mercado which has a 36-column gallery in front of it, and a small ballcourt.

Great Ballcourt

The Great Ballcourt of Chichen Itza, measuring 146 m x 36 m, is the largest in Mesoamerica. It was constructed between 1050 and 1200 CE and is also unusual in that the sides of the court are vertical and not sloped as in most other courts. Temple platforms close off each end of the court. The lower parts of the walls and the ring on each wall are decorated with carvings of snakes. The dimensions of the court are so grand that it is difficult to envisage actual games being played here. The rings, for example, through which players had to direct the solid rubber ball, are placed at a height of 8 m. The relief carvings on the walls of the court remind us of the ritual function of ball games; for example, there is a gruesome scene of two seven-man teams facing each other and one team captain decapitating the losing captain of the opposition. It is a scene repeated on all six relief panels along the two benches of the ballcourt.

Tzompantli

Near the great ballcourt a large platform takes the form of a skull rack or tzompantli, and a second platform, the Platform of the Eagles, has relief carvings depicting jaguars and eagles eating human hearts. Both were built 1050-1200 CE, and they are further indicators that human sacrifice was a part of religious ceremonies at Chichen Itza.