The so-called Children's Crusade of 1212 CE, was a popular, double religious movement led by a French youth, Stephen of Cloyes, and a German boy, Nicholas of Cologne, who gathered two armies of perhaps 20,000 children, adolescents, and adults with the hopelessly optimistic objective of bettering the failures of the professional Crusader armies and capturing Jerusalem for Christendom. Travelling across Europe, the would-be Crusaders perhaps reached Genoa but had no funds to pay for their passage to the Levant. While some participants simply returned home, a large number were sold into slavery, according to the legend. Whatever the exact events of the confused history of the 'Children's Crusade', the episode illustrates that there was a popular sympathy for the Crusade movement amongst the common people and it was not just nobles and knights who felt compelled to take the cross and defend Christians and their sacred places in the Holy Land during the Middle Ages.

Objective Jerusalem

Saladin, the Muslim Sultan of Egypt and Syria (r. 1174-1193 CE), had shocked the Christian world when he captured Jerusalem in 1187 CE. Despite the failure of the Third Crusade (1187-1192 CE) to then even get in touching distance of Jerusalem, and the even more dismal Fourth Crusade (1202-1204 CE), which had instead attacked Constantinople, there were still many Christians in the west eager to travel to the Holy Land and help in the task of retaking Jerusalem. There was perhaps, too, a frustration among the ordinary populace that despite the taxes they were asked to bear and the sacrifices in materials and supplies to repeatedly furnish Crusader armies, the primary objective of retaking the Holy City had still not been achieved. In 1212 CE a curious movement sprang up which has since gained legendary status. Thousands of children were organised into an 'army', and they set out for the Middle East thinking that they could do a whole lot better than the adults in defeating the Muslim infidels.

Stephen & Nicholas

In the spring of 1212 CE, in the region of Vendôme in France, groups of youths claimed to have experienced visions which prompted them to set off and fight the Muslims in order to regain Jerusalem. Their leader was one Stephen of Cloyes, a shepherd. According to the legend, Stephen had approached king Philip II of France (r. 1180-1223 CE) claiming, while tending his flock one day, to have miraculously received a letter from the hands of Jesus Christ. The letter instructed Stephen to go forth and preach the Crusade, gathering followers wherever he went. The king dismissed these claims and Stephen, too, but the boy, undeterred, went on a preaching tour of the region anyway and he began to accumulate a significant number of followers, the majority of whom were children.

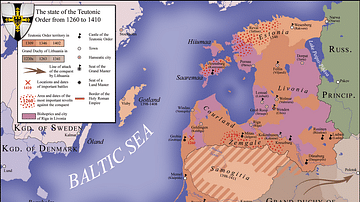

Also in 1212 CE, groups of young people gathered in the region of Cologne in Germany. As with northern France, the Low Countries and the Rhineland were also areas where the Church had been evangelising with a passion to garner support for official Crusades. In Cologne a young leader emerged, a local boy called Nicholas, who carried around a tau cross (which resembles the letter T). Whether the French group influenced the German or vice versa, or whether each was wholly independent of the other is not clear from the medieval sources, which are hopelessly confused, inconsistent, and conflicting on the whole affair.

Mobilisation

There is some debate as to whether this popular crusading movement was entirely formed by children as the medieval records are so confused and the term most often used for the participants, pueri, may include children, adolescents and adults. Indeed, some Norman and Alpine monks recorded that the pueri, in this case, included adolescents and old people. Nevertheless, the movement was significant because it involved people not usually so directly connected with crusading. As the historian C. Tyerman here elaborates,

Accounts indicated that participants came from outside the usual hierarchies of social power - youths, girls, the unmarried, sometimes excluding even widows - or economic status: shepherds, ploughmen, carters, agricultural workers and rural artisans without a settled stake in land or community, rootless and mobile. Signs of anti-clericalism and the absence of clerical leadership accentuated this sense of social exclusion. (609)

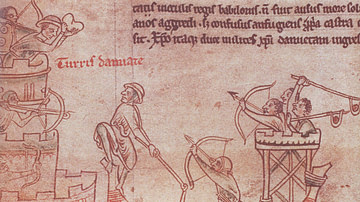

A Crusade was typically called by the Pope, who urged rulers, nobility, and professional knights to take up arms in the causes of Christianity. Commoners were generally discouraged from participating as they did not have the means, skills or discipline required for such a vast military mobilisation across Europe. The 'Children's Crusade', as it has become known, then, was certainly not an official Crusade sanctioned by the Church.

It is estimated that 20,000 'children' set off and crossed both Germany and France - either separately or, at one point joining forces (medieval sources allow both interpretations) - with the aim of reaching the Italian port of Genoa where they might find ships to take them to the Holy Land. Some groups may have made their way to the alternative ports of Pisa further south, Marseille in southern France, or even Brindisi in the south of Italy.

Unfortunately, many of the travellers, depending entirely on charity wherever they went, died of hunger crossing the Italian Alps, and when the remainder arrived at Genoa, they had no funds to pay for their passage so that, without any military equipment or training, the Genoese refused to help. In some versions of the legend, the children had optimistically expected the Mediterranean, like the Red Sea for Moses, to miraculously open and allow them to pass through to the Levant.

After neither the miracle or the offer of material help by the Genoese was forthcoming, some of the children, almost certainly a small minority, trudged home. What exactly happened to the remainder has been lost in the legends created by later medieval writers and moralists. According to some sources, most of the children were shipped off to Sardinia, Egypt, and even Baghdad, and there sold into slavery. However, this version of events may have less to do with real events and more to do with the Church's desire to treat the whole affair as a morality tale, a stark warning to others that only crusades with papal authority were ever likely to succeed. Indeed, in some versions of the story, the children made it to Rome, where the Pope promptly told them all to go back home. A rabble of beggars without the means to support themselves and without the military training and arms to do any good if they ever managed to reach the Holy Land was of no use to anyone.

Aftermath

There would be other such popular Crusader movements, notably the Shepherd's Crusades of 1251 and 1320 CE, which, like the children's escapade, never managed to leave the shores of Europe. Crusading, especially when travelling to the Holy Land by ship became the norm instead of the longer and more arduous land route, was, unlike the chaotic early days of the First Crusade (1095-1102 CE), now a wholly professional movement. The official Crusades which immediately followed were the Fifth Crusade (1217-1221 CE), which attacked Muslim held cities in North Africa and Egypt, and the Sixth Crusade (1228-1229 CE), led by Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II who negotiated control of Jerusalem from Saladin's nephew. Curiously, there is a tradition in one Alpine monastery that Nicholas of Cologne made his way there after the failure to find ships for his followers and that he did eventually join an official Crusade, fighting the Muslims at Damietta on the Nile.