Chiusi (Etruscan name: Clevsin, Roman: Clusium), located in central Italy, was an important Etruscan town from the 7th to 2nd century BCE. Relations with the Romans famously soured when the king of Chiusi, Lars Porsenna, attacked Rome at the end of the 6th century BCE and contributed to the ending of Rome's monarchy. Nevertheless, despite the Republic's growing stature, Chiusi prospered well into the Hellenistic period. The town's many stone tombs have revealed vibrant wall paintings, fine Etruscan artworks, large terracotta sarcophagi, and the world-famous Greek black-figure krater, the Francois Vase.

Early Settlement

Located in central Italy just west of Lake Trasimene, Chiusi was a Villanovan settlement (1000-750 BCE), the culture which was a precursor to the Etruscans. Early tombs at the site contained large terracotta vessels inside which were placed 'Canopic' jars containing the cremated remains of the deceased. The jars, typically half a metre in height, are made to resemble human figures, sometimes with a bronze mask attached, dressed in clothing, belts, and jewellery, and seated on miniature thrones of stone, bronze, or terracotta. The jars illustrate Chiusi's, and Etruria's in general, adoption of art and cultural practices from the Eastern Mediterranean, although Chiusi's preference for cremation of its dead lasted longer than in other Etruscan towns. From the 7th century BCE, the dead were interred in rock-cut tombs often consisting of one main chamber and several smaller side rooms. Some of the earlier stone tombs also contain 'Canopic' jars illustrating a gradual change in burial practices. Some of the tombs have interior wall paintings depicting scenes from Greek and Etruscan mythology.

A Thriving Etruscan Town

Chiusi was a member of the Etruscan League, a loose confederacy of 12 (or perhaps 15) Etruscan towns (or peoples). They included Cerveteri (Cisra), Populonia (Puplona), Tarquinia (Tarchuna), and Vulci (Velch). Very little is known of this league except that its members had common religious ties and that leaders met annually at the Fanum Voltumnae sanctuary near Orvieto (exact location as yet unknown).

Chiusi benefitted from fertile agricultural lands to produce cereals, forests for timber, and its location on inland routes connecting various other Etruscan towns. These routes followed natural valleys and rivers such as the Tiber and Arno, making Chiusi an important point of connection between northern and southern Etruria. Indeed, Chiusi's trade tentacles stretched much further, as finds of bronze vessels from the town found at Celtic sites in Switzerland and Germany attest. From inscriptions, which the town is particularly rich in, it also seems that citizens of Chiusi participated in the general expansion northwards of the Etruscan cities, establishing colonies in the Po Valley, still then relatively uninhabited.

Chiusi had its own manufacturing workshops and was noted for its bronze work (especially cauldrons and candelabras) and stone-carving. The latter used the local fine limestone known as pietra fetida and was carved, in particular, for funerary containers, sarcophagi, stelae, and tomb markers. These objects were carved with decorative relief scenes of daily life, episodes from mythology, and such guardian creatures as sphinxes and winged lions. The stone was then painted in bright colours, largely now lost on surviving examples. Another type of production was bucchero wares, the glossy almost black pottery made by the Etruscans.

Relations with Rome

A famous figure from Chiusi is Lars Porsenna, the king who, according to tradition, laid siege to Rome c. 508 BCE. According to Roman sources, he wanted to put Tarquinius Superbus back on the throne, who was, like many of the city's early kings, of Etruscan origin. Porsenna finally withdrew after being impressed with his enemy's fortitude and moved off to attack the Latin town of Aricia instead, albeit without success. Another version of the story has Porsenna victorious and Rome surrendering to the Etruscan king, who then, far from reinstalling Superbus, acted to abolish the monarchy of Rome and then attacked Aricia. In the event, Superbus would indeed turn out to be Rome's last king as the Republic set off on its road to greatness. The Roman writer Pliny writes of an impressive monument and tomb to Porsenna which was located outside the city walls of Chiusi and included five huge pyramids, no evidence of which survives today.

Chiusi seems to have avoided the general decline that other Etruscan cities suffered, especially the coastal ones following the rise of Syracuse in the 5th-4th century BCE and its takeover of lucrative maritime trade routes. Judging by the tombs and grave goods of the 3rd century BCE, the city was as prosperous as ever, even if an attack by northern Celts had to be resisted. There is evidence that, in the 2nd century BCE, such was Chiusi's wealth, manifested in the landed elite's great demand for funerary art, that artists relocated from declining Etruscan towns like Tarquinia which had failed to meet the challenge of Rome in the 2nd century BCE. Still, Chiusi's turn would eventually come, and by 80 BCE, following the campaigns of Sulla, the town was fully assimilated into the Roman Republic, its residents made Roman citizens, and the Etruscan culture thus faded into the past.

Archaeological Remains

The tombs of Chiusi have given the world some prize objects. One of these is the celebrated Francois Vase. This large Attic volute-krater, dating to c. 570-565 BCE, is perhaps the example par excellence of the Greek black-figure pottery style with its 270 human and animal figures in scenes from a whole range of myths. Other, less significant finds include bronze incense burners, glass perfume bottles, carved ivory boxes, gold jewellery pieces with granulation and repousse work, and incised gilt-silver vessels.

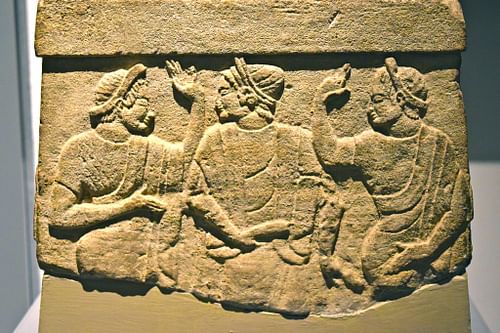

Tomb Markers & Figures

Several examples of 6th century BCE tomb markers survive, which probably acted as guardians. They once had a round column-drum base and a top carved into a bust of a woman who has her hands clasped together on her chest. Another type of stone funerary statue, and perhaps used as a container for the ashes of the deceased they may have represented, are carved hollow statues of men and women, either standing or seated on a throne. Sarcophagi and stelae show scenes of everyday life and reveal such details as women's clothing (belted long dresses and short cloaks), funeral dances accompanied by musicians (including men and women dressed as satyrs and maenads, respectively), funeral sporting games, weddings, banquets where both men and women are present, and chariot races with details such as spectators, record keepers, and wineskins for the victors.

Tomb Wall Paintings

Tombs with wall paintings include the Tomb of the Monkey, constructed 480-470 BCE, which has a scene of a monkey sitting in a tree and another where a woman wearing a red robe is shown seated under a parasol with her feet up on a stool while she watches a parade of jugglers, athletes, dancers, and chariots. Intriguingly, the artist may have used a template for his subjects as not only do some of the scenes closely resemble those in tombs at Tarquinia but also a pair of boxers, who stand facing each other, mirror each other's outlines exactly.

Hellenistic Tombs

Tombs from the Hellenistic period at Chiusi are in two forms. One type is constructed from well-cut blocks and has a barrel vault much like Macedonian tombs. The second type has a much more impressive entrance tunnel; some are up to 25 metres in length. The interiors, conversely, are plainer with a simple rectangular or cross-shaped chamber lined with benches and niches on which were placed funerary jars and sarcophagi. The names of the tomb's occupants are often inscribed on large terracotta tiles which were used to close off the niches. These tombs were used over several generations, and in some cases, the entrance tunnels became the tomb itself with no end chamber. One example has 39 niches and appears to be a forerunner of the later Roman columbaria tombs which housed large numbers of the dead.

Funerary Jars & Urns

Besides the 'Canopic' funerary urns described above, another container of ashes produced in large numbers at Chiusi during the 2nd century BCE was composed of a rectangular base with a single sculpted figure reclining on the lid (a few examples have a couple). Made using molds from terracotta, the bases have relief scenes from mythology (especially battles and perhaps echoing the Etruscan struggle with Rome) while the top figure, presumably an idealised (but not always) representation of the owner of the ashes kept in the urn, is depicted either sleeping or reclining while enjoying a banquet. The urns were brightly painted over a white slip using reds, blues, and yellows. Other, smaller pottery urns from the Hellenistic period have an unusual bell shape and are painted with garlands on a white background.