Chlothar II was a Merovingian king of the Franks, who reigned from 584 to 629. He inherited the throne of Neustria as an infant, upon the assassination of his father, Chilperic I (r. 561-584). Following a long and bitter power struggle with Brunhilda of Austrasia and her descendants, Chlothar united all Francia beneath his rule in 613.

The reigns of Chlothar II and his son Dagobert I (r. 623-639) are often considered to be the peak of Merovingian power and were a time of peace and prosperity for the Frankish realms. However, Chlothar paid a steep price for this success, as he was forced to concede more power to the aristocracy and to the mayors of the palace, an office that was essentially the king's right-hand man. As a result, Chlothar II and Dagobert I would be the last Merovingian rulers with any real authority before the mayors of the palace became the true powers behind the throne.

Blood Feud

Much of the reign of Chlothar II was dominated by a feud that had begun a decade and a half before his birth. In 567, there were three Merovingian kingdoms in Gaul, each ruled by a son of the powerful King Chlothar I (r. 511-561):

- Guntram I of Orléans (r. 561-592) ruled over the territory of Burgundy

- Sigebert I (r. 561-575) ruled the eastern kingdom of Austrasia

- Chilperic I (r. 561-584) ruled in Soissons over the territory that would soon be known as Neustria

Each brother was insatiably ambitious and dreamed of reigning over a united Frankish kingdom in the manner of both their father, Chlothar I, and grandfather, Clovis I (r. 481-511).

As part of their efforts to outdo one another, Sigebert and Chilperic each married a daughter of the Visigothic king Athanagild; Sigebert married Brunhilda, and Chilperic took Galswinth as his bride. But Chilperic was unhappy with his new wife and had her strangled in her sleep before marrying his mistress, a lowborn woman named Fredegund. The murder of Galswinth created friction between the brothers, resulting in a devastating civil war from 572-575. At the end of the war, King Sigebert, on the cusp of achieving victory, was assassinated by servants hired by Queen Fredegund. The kingdom of Austrasia passed to Sigebert's 5-year-old son, Childebert II (r. 575-596) who now ruled with the protection of his uncle Guntram and mother Brunhilda. Fredegund's involvement in the murders of both Brunhilda's sister and husband sparked a bitter rivalry between the two queens that would dominate the reigns of their sons.

Prior to 584, Chilperic had had seven sons, all of whom had died, either by disease, battle, or murder. His eighth son, the future Chlothar II, was born in May or June 584. The tendency of their boys to die premature deaths caused Chilperic and Fredegund to send their newborn son off to the royal estate of Vitry-en-Artois, to be raised in relative secrecy. But the prince had only been there a few months when, in September or October 584, King Chilperic was assassinated by an unknown assailant. His sudden death thrust all Francia into a period of chaos; Austrasian soldiers raided lands along the Neustrian border, a pretender named Gundovald claimed the kingship of Aquitaine, and certain rival cities began warring against one another.

Meanwhile, Queen Fredegund knew she had to act fast if she was to ensure her son's ascension to the throne. First, she secured the loyalties of key Neustrian magnates, who traversed the kingdom extracting oaths of loyalty from cities and villages. Then, in 585, she wrote to King Guntram, the boy's uncle, and asked him to provide to Chlothar II the same offer of protection he had bestowed upon Childebert II. Guntram, who had just finished crushing Gundovald's revolt, was initially hesitant; he distrusted the devious and power-hungry Fredegund and openly questioned whether Chlothar was truly his nephew.

To put Guntram's mind at ease, Queen Fredegund, three bishops, and 300 Neustrian nobles all swore solemn oaths affirming that Chlothar II was indeed the natural son of the late King Chilperic. This seemed to satisfy Guntram's concerns; he adopted the boy and hosted his baptism in Paris. This made Guntram the most powerful man in Francia, holding all three kingdoms in trust for his young nephews. For Fredegund, this was an unpleasant but necessary compromise; by submitting herself to Guntram, she kept herself and Chlothar out of the clutches of Brunhilda.

Struggle for Survival

King Guntram was old, and his protection could only last for so long. He died in 592, and his entire kingdom passed to Childebert II, who had been made Guntram's heir in the recent Treaty of Andelot. Unlike his uncle, Childebert had no interest in preserving his young cousin's independence; indeed, he had not forgotten the murder of his father at the hands of Queen Fredegund. Egged on by his mother Brunhilda, Childebert assembled an army from across his double kingdom of Austrasia-Burgundy and sent it to march on Soissons.

Since Chlothar II was still only eight years old, the defense of Neustria fell to Queen Fredegund and Landri, Neustria's mayor of the palace. In 593, the smaller Neustrian force attacked the invading Austrasians at the Battle of Droizy, utilizing the element of surprise to compensate for their numerical disadvantage. In the early hours of the morning, the Neustrians snuck up within marching distance of the Austrasian camp, and then formed up for battle; the horsemen were positioned behind the infantry, who carried tall tree branches to conceal the army from view.

As the camouflaged Neustrians crept forward, they were spotted by an Austrasian sentry, who reported to his superiors that he had seen a moving forest marching on the camp. The man was laughed off as a drunkard, allowing the Neustrians to take the Austrasians completely by surprise, slaughtering many of them and scattering the rest. Fredegund apparently even rode into battle with her son on her lap to help inspire the troops. The Battle of Droizy contained the first instance of 'moving trees' marching into battle and may have helped inspire a crucial plot point in William Shakespeare's Macbeth.

After their victory at Droizy, the Neustrians pursued the Austrasians all the way to Rheims, plundering and burning the surrounding territory before withdrawing back to Soissons. Before Childebert II could mount a retaliatory campaign, he died in 596; since he was only in his mid-twenties, it was likely that he had been poisoned. Chlothar and Fredegund took advantage of his death by sending an army to occupy Paris and other lands along the Seine. When Childebert's two sons, Theuderic II and Theudebert II, sent an army against the Neustrians, they were defeated at Laffaux. For a time, it must have seemed that Chlothar and his mother were invincible.

On 8 December 597, Queen Fredegund died of natural causes. Chlothar II, now left to rule Neustria alone, took up his mother's cause and continued the rivalry with Queen Brunhilda and her grandsons. In 599, Theuderic II of Burgundy joined forces with his brother Theudebert II of Austrasia, and the pair prepared to launch a new attack against their cousin Chlothar. Chlothar II was at an obvious disadvantage; between them, Theuderic and Theudebert controlled three times more territory than Chlothar did and could draw from a much larger pool of manpower and resources. When the brothers finally invaded Neustria in 600, they defeated Chlothar at the Battle of Dormelles, slaughtering the Neustrian soldiers.

They followed up their victory by attacking the towns along the Seine that Chlothar had recently captured, laying waste to fields, and carrying off townspeople and plunder. Realizing he had been defeated, Chlothar made peace with his cousins, ceding to them enormous amounts of territory that left him with only 12 pagi, or counties, between the Seine, the Oise, and the sea. The tide had turned, and Chlothar was now at the mercy of Brunhilda and her grandsons.

The Civil War Continues

Chlothar spent four years biding his time, before striking again in 604. Theuderic II had sent a small force under his mayor of the palace, Bertoald, to inspect his newly won territories along the Seine. When Chlothar found out Bertoald's location, he sent an army under his own mayor, Landri, to deal with him. The Neustrians took the Burgundians by surprise, chasing them all the way back to Orléans, which they besieged in November.

Theuderic quickly put together another army and marched against the Neustrians, and the two sides fought the Battle of Étampes in December 604. Bertoald was killed while leading the Burgundian vanguard; some chroniclers later suggested his death was engineered by Brunhilda herself, to advance her own position at her grandson's court. But despite the loss of Bertoald, the Burgundians ultimately won the battle and routed the Neustrians. Chlothar's infant son, Merovech, who was accompanying the army, was captured and later put to death by Brunhilda. Chlothar had no choice but to agree to a peace with Theuderic in 605.

Significantly, Theuderic II had not been aided by his brother in this second war against Chlothar. This reflected the deep hostility that had been brewing between the two brothers and their courts, an argument that centered around the overbearing influence of Queen Brunhilda herself. In the court of Burgundy, where Theuderic reigned, Brunhilda still enjoyed a great deal of support from the Romanized Burgundian nobles. But in Austrasia, where the nobility was primarily of Frankish culture, she faced much more hostility. Theudebert II himself despised having to submit to his grandmother's whims and ousted her from his court. Scorned, Brunhilda travelled to Orléans, where she convinced Theuderic to make war on Theudebert, going so far as to persuade him that Theudebert was not really his brother but was instead the bastard son of a gardener.

War broke out between Burgundy and Austrasia in 610 and climaxed in 612 with the two colossal battles of Toul and Zülpich. According to the Chronicle of Fredegar, these battles were so destructive that men died standing up since there was no room for their bodies to fall amongst the carnage. Theuderic, who won both battles, captured and executed his brother, before consolidating his victory by bashing out the brains of Theudebert's infant son. Theuderic would not live long enough to bask in the glory of his victory, as in 613, he died of dysentery. The throne of the combined kingdom of Austrasia-Burgundy, therefore, passed to Theuderic's infant son, Sigebert II. Brunhilda once again became regent, ruling the kingdom in the name of her great-grandson.

A Long-Awaited Vengeance

The true winner of the civil war was Chlothar II. Theuderic had given him a good deal of land to ensure Neustrian neutrality during the war. Now that it was over, Chlothar emerged all the more powerful, his only remaining threats being an infant child and a despised old woman. By now, many of the Austrasian and Burgundian nobles were sick of Brunhilda. The last straw came when the queen attempted to consolidate her power by assassinating Warnachar, mayor of the palace of Austrasia. Warnachar survived, and joined forces with other powerful nobles, like Rado, mayor of the palace of Burgundy, Arnulf of Metz, and Pepin of Landen, to invite Chlothar to take the thrones of Austrasia and Burgundy.

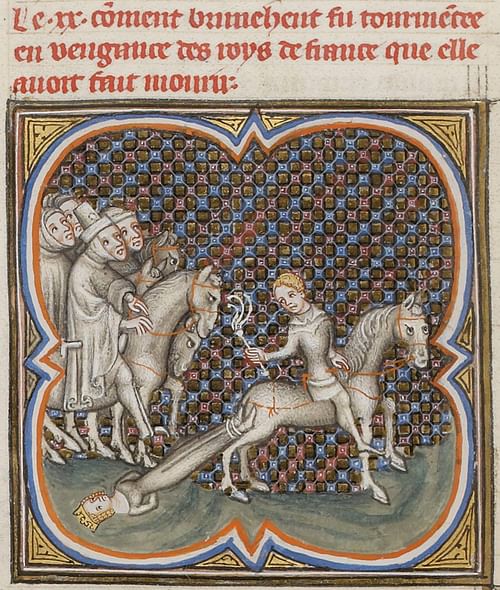

Chlothar accepted and launched an invasion. Brunhilda assembled an army to resist him, but her soldiers deserted in droves, and Brunhilda herself was captured by her treacherous nobles and delivered to Chlothar in chains. Now victorious, Chlothar had Sigebert II and Brunhilda's other great-grandchildren put to death. Brunhilda herself, his mother's bitter enemy, Chlothar reserved a much grislier fate. Charged with the deaths of no fewer than ten Merovingian princes (most of these accusations were dubious at best), Brunhilda was tortured for three days before being tied to the limbs of horses and ripped apart. With her death in 613, the conflict that had driven Merovingian politics for close to half a century came to an end, and Chlothar II became the ruler of a reunited Frankish kingdom.

Council of Paris

Chlothar II claimed the coveted title 'King of All the Franks' upon his victory in 613, a title which had first been used by Clovis I. To kick off his new reign, he convoked the Council of Paris in 614, which was attended by a great number of nobles and ecclesiastics from across his three kingdoms; 76 metropolitan and suffragan bishops attended, including at least two bishops from as far away as England. The fact that the council was so well-attended proved that, barely a year into his tenure as King of the Franks, Chlothar enjoyed considerable authority and influence.

Chlothar used the council to further strengthen his position. He laid the blame for the last four decades of conflict entirely at the feet of Brunhilda and her offspring. While he upheld any edicts that had been made by his father Chilperic and uncle Guntram, Chlothar struck down any tolls or policies that had been passed by the son or grandsons of Brunhilda. Chlothar then brought up several matters for the attendees to discuss, the result of which was the seminal Edict of Paris of October 614. The edict, which has been considered by some historians to be a Merovingian Magna Carta, essentially bolstered the power of the aristocracy in the three Frankish kingdoms of Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy. It affirmed the traditional rights of the nobility and clergy, and fostered a system of decentralization, where local authorities were largely responsible for maintaining law and order in their own lands; the edict famously stipulated that no local judge or official could prosecute a man from a different province.

The power of the aristocracy was further bolstered in 617 when Chlothar appointed Warnachar mayor of the palace of Burgundy for life. While this was intended to apply only to Warnachar himself, perhaps as a reward for having turned against Brunhilda, the action greatly increased the power and prestige of the office. A position that had once been nothing more than the head of the king's household was now the second most powerful position in the Frankish realm; in only a few more years, it would be the most powerful. Chlothar kept a mayor of the palace in place in each of his three kingdoms, thereby creating three distinct power bases within his realm. Through the Edict of Paris and the elevation of the mayors of the palaces, Chlothar had secured his own position, but at the expense of crown authority.

Later Reign

Chlothar spent much of his reign working to bind the various groups of nobles in his realm together. He established a permanent royal court in Paris, making him unique from previous Merovingian rulers, whose courts usually travelled around with them. The court became a popular hub for nobles from all three kingdoms. Noble children were sent there to be educated, and aristocrats travelled to the court to arrange marriages or establish alliances.

While this helped create a sense of cohesion by familiarizing the aristocrats of each kingdom with one another, having a central court helped strengthen Chlothar's own power as well. He would take note of the regional elites arriving in Paris and would handpick several of them to be re-educated and trained to support Chlothar's own desired policies. Once he was certain of their loyalties, he would send them back to their home provinces to rule in his name. Chlothar also kept a man at court whose purpose was to sniff out conspiracies and assassinate potential threats. Through these methods, Chlothar used his court to keep the aristocracy on as much of a leash as he could with respect to the Edict of Paris.

Still, the new power of the aristocracy compelled Chlothar to continue making concessions to them. In 623, the Austrasian aristocracy voiced their annoyance that Chlothar held court in Neustria; they felt that the Neustrians unfairly benefited from their easy access to the king's ear and demanded Chlothar move to Austrasia. While Chlothar had no intention of doing this, he could not risk upsetting the Austrasian magnates by ignoring their concerns. Instead, he decided to carve off Austrasia from the rest of his realm, turning it into a semi-autonomous subkingdom ruled by his eldest son, Dagobert I. While the Merovingian kingdoms had typically been partitioned upon succession, this particular partition was novel in that it established the boundaries that would go on to define the kingdoms of Neustria and Austrasia.

Chlothar II was known as a pious king; he held multiple synods during which he granted increased authority to the church, and he looked after the monastery of Luxeuil, which had been founded by Saint Columbanus. By 629, Chlothar had been married to three women, by whom he had fathered two heirs: Dagobert I and Charibert II. While Dagobert was considered a competent heir to carry on the Merovingian legacy, there was less confidence placed in Charibert's abilities, who was described in the Chronicle of Fredegar as "simple-minded".

Chlothar II died in October 629 at the age of 45. His reign was amongst the longest of any Merovingian king, second only to that of his grandfather Chlothar I. His realm was divided up between his sons, with Charibert II getting Aquitaine and Dagobert getting the rest. When Charibert II died prematurely in 632, Dagobert ruled alone as King of All the Franks, becoming the last Merovingian king to exert any substantial royal power before the mayors of the palace began running the show.