Christopher Columbus (l. 1451-1506 CE, also known as Cristoffa Corombo in Ligurian and Cristoforo Colombo in Italian) was a Genoese explorer (identified as Italian) who became famous in his own time as the man who discovered the New World and, since the 19th century CE, is credited with the discovery of North America, specifically the region comprising the United States.

Actually, owing to the early 16th-century CE popularity of the published letters of the Florentine explorer Amerigo Vespucci (l. 1454-1512 CE), detailing his three voyages to the “New World” between 1497-1504 CE, the discovery of the Americas has been credited to him on world maps beginning in 1506 CE which is why the continents bear the feminine version of his name.

Columbus made four voyages to the area of the Caribbean, exploring Cuba, Central America, South America, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, the islands of the Bahamas, and others between 1492-1504 CE:

- First Voyage: 1492-1493 CE

- Second Voyage: 1493-1496 CE

- Third Voyage: 1498-1500 CE

- Fourth Voyage: 1502-1504 CE

Columbus never set out to discover a New World, but to find a western sea route to the Far East to facilitate trade after the land route of the Silk Road, between Europe and the East, had been closed by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 CE, initiating the so-called Age of Exploration (also known as the Age of Discovery) which launched many European sea expeditions. Columbus' first voyage brought him to one of the islands of the Bahamas on 12 October 1492 CE, which he claimed in the name of the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and his wife Isabella of Castile of Spain. His next three voyages were made to consolidate Spain's control of the region and establish colonies.

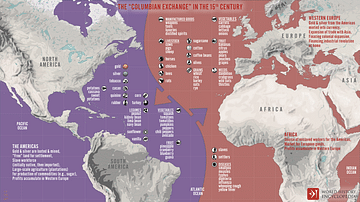

Columbus is acknowledged as the first to establish contact between Europe and the Americas known as the Columbian Exchange whereby people, plants, technology, and other aspects of culture passed between the Old and the New World, transforming both and establishing the foundation for the modern age.

Although modern-day detractors of Columbus cite the Norse community in Newfoundland as the first “discovery of America”, the Vikings under Leif Erikson, who landed in North America centuries before Columbus, had no effect on the indigenous population and their return to Greenland afterwards inspired no further expeditions.

Columbus' journeys, by contrast, opened the way for later European expeditions, but he himself never claimed to have discovered America. The story of his “discovery of America” was established and first celebrated in A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus by the American author Washington Irving (l. 1783-1859 CE) published in 1828 CE and this narrative (largely fictional) would eventually contribute to the establishment of Columbus Day as a United States' holiday in 1906 CE, observed up through the present.

In the 1970s CE, however, a revaluation of Columbus and the effects of his voyages on the culture and people of the Americas has increasingly called for discarding this tradition in favor of honoring the indigenous people adversely affected by the four expeditions he made to the New World and the poor treatment of the original population at the hands of the European immigrants afterwards. This debate continues in the present.

Early Life & the Silk Road Closure

Columbus was born in Genoa in 1451 CE which was then in the region of Liguria and only much later (in 1861 CE) would become part of Italy. He had three brothers – Bartolomeo, Giovanni, and Giacomo (regularly referred to as Diego), and a sister, Bianchinetta. His father, Domenico, was a weaver and tavern-keeper whose love of sea travel would significantly influence young Columbus and his mother, Susanna, a housewife.

Little is known of Columbus' early life (though he claims to have been sailing by age ten) but, by the time he was 20 years old, he was already experienced at seamanship (having traveled to Iceland and the Aegean Sea) and, by 1476 CE, he was entrusted with his own command of a trading vessel. He was married to the Portuguese noblewoman Filipa Moniz Perestrelo and had a son, Diego, by 1480 CE and, by 1485 CE, was piloting ships to areas along the coast of West Africa in the service of Portugal's trade interests.

The climate in which Columbus had grown up was significantly different from that of his parents in that the kinds of goods Europeans had grown used to were no longer available in the way they had once been. The overland trade routes to the East, known in the modern era as the Silk Road, had been in operation between Europe and China since 130 BCE when it was opened under the Han Dynasty (202 BCE - 220 CE).

The Silk Road was comprised of numerous routes, parts of which fell under the control of one group or nationality or another at various times in its history. The European explorer Marco Polo (l. 1254-1324 CE) traveled the Silk Road and dictated details of it in his book after he returned which provided later travelers with a kind of guide and also helped them establish distances between Europe and the East.

The Silk Road was predominantly controlled by the Mongol Empire until its fall in 1368 CE after which the Byzantine Empire (330-1453 CE) kept goods flowing in both directions. The Byzantines fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453 CE, however, who then closed the overland routes and cut European merchants off from Eastern goods. In an effort to re-establish trade with the East, European merchants took to the sea, launching the so-called Age of Discovery.

The Age of Discovery & Funding

This is not to say that Europeans had no knowledge of sea travel at this time nor that European merchants suddenly scrambled to build ships or hastily draw inaccurate maps. The magnetic compass was known in Europe by 1180 CE and, using ancient texts such as Strabo's Geography and Pliny the Elder's Natural History as well as long-established maps, European pilots were able to navigate the waters and continue trade with the East via the Black Sea.

The problem they faced, however, was Muslim Arab traders who controlled a number of significant sea routes to the East. Portuguese mariners began looking into other possible sea routes to the East, and one contributor to this effort was the Florentine astrologer and mathematician Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (l. 1397-1482 CE) who had transcribed a map of the world of the ancient geographer Strabo (l. 63 BCE - 23 CE) and presented a copy to King Alfonso V of Portugal (r. 1438-1481 CE), suggesting sailing west in order to reach the Cathay (China) in the East.

Alfonso V rejected Toscanelli's proposal and so the latter sent the copy of the map to Columbus, who by now had a reputation as an expert navigator and seaman, in 1474 CE. Columbus was still sailing in the interests of Portugal at this time, and he and his brothers were also engaged in working out a sea route to Cathay. Columbus had taught himself Latin, Spanish, and Portuguese and so was able to access a wide range of documents and maps in developing his vision of a voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to establish a new trade route with Cathay.

The Columbus brothers put together a plan and, c. 1484 CE, Columbus approached King John II of Portugal (r. 1481-1495 CE) to request funding. Columbus, basing his calculations on Toscanelli's map, Marco Polo's work, and other documents, estimated the distance from the Canary Islands to Cathay at around 2,300 miles (3,700 km), but King John II rejected the plan on the grounds that Columbus' estimate of the distance was too low (which proved to be true, as the distance was actually 12,200 statute miles or 19,600 km). Columbus then brought his proposal to the governments of Genoa and Venice but was rejected by both.

He then turned to Ferdinand II and Isabella I of Spain who also rejected him but were intrigued enough by his plan that they kept him on retainer, paying him a significant sum to keep him from proposing the expedition to any other government. Ferdinand and Isabella were in the midst of their own problems trying to drive the Muslim Arabs, known as the Moors, from their territory in the effort which has since come to be known as the Reconquista (711-1492 CE). The last stronghold of the Moors at Granada fell in 1492 CE, and, afterwards, Columbus was granted the three ships and funding he had requested.

The Voyages

Columbus left port on 3 August 1492 CE in his famous ships the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria. His main objective was reaching Cathay, but it was also made clear that he was to claim any lands not already under a sovereign nation for Spain and to the honor of the Catholic Church. To this end, he was given two official documents:

- A contract between him and the crown promising the monarchy 90% of the profits of the venture in return for funding and stipulating that Columbus was awarded the position of viceroy or governor of any lands he took for the crown.

- A letter of introduction from Ferdinand and Isabella requesting any monarch Columbus came in contact with to provide him safe passage and provision as his mission was in the service of the Christian faith.

First Voyage - 1492-1493 CE: He arrived at an island in the Caribbean on 12 October 1492 CE and was greeted by a large gathering of indigenous people on the beach. He summoned the captains of the Nina and Pinta and rowed to shore along with the secretary of the fleet and the royal inspector. He knew he had not landed at Cathay but believed he had discovered an island near to his objective which, as far as he could tell, was not claimed by any sovereign nation and so he claimed it for Spain, and this was duly noted by his witnesses.

He was given to understand by the natives that their island was called Guanahani, but he named it San Salvador (still its present name in the Bahamas). The natives (the Arawaks) probably also gave him the name they called themselves, but he referred to them as indios and so established the use of the term Indian for the people of the region and, later, for those of North, Central, and South America. No mention is made of the reactions of the people who had come to greet them, and, shortly afterwards, the five Europeans and the native islanders exchanged gifts of friendship.

Second Voyage - 1493-1496 CE: Columbus arrived back in the New World as governor of the lands he had claimed with a fleet of 17 ships full of colonists to establish communities for Spain as well as a number of dogs to be used in subduing the natives. The Mastiff had been successfully used by the Spanish against the Moors in the Reconquista and so were included as an important asset in Columbus' second voyage.

The dogs terrorized the native people, hunted down those who were accused of dereliction of duty, and broke any attempts at resistance to the European conquest. When he arrived in Jamaica in 1494 CE, he was opposed by defenders on the beach until he released the savage mastiffs which terrorized the indigenous warriors and scattered them.

The Second Voyage established the encomienda system in which Spanish settlers claimed a large tract of land on which the natives provided labor in return for food, shelter, and protection from those they labored for. By 1495 CE, the indigenous population had decreased, according to the later works of Las Casas, by 50,000 and, although that number is considered an exaggeration by many modern scholars, it is most likely too low.

The natives of the region were reduced from autonomous individuals with an established culture to slaves who could be tortured or killed for any reason at any time and suffered significant losses through European diseases they had no immunity from. Losses also stemmed from a significant portion of the populace shipped off to Europe as slaves.

Third Voyage - 1498-1500 CE: Although the Europeans had now firmly established themselves in the New World, Columbus had yet to find a way through the islands he had so far visited and reach Cathay. He was certain that the lands he had colonized for Spain were outliers of the continent of Asia and so, after his return to Spain in 1496 CE, his Third Voyage was funded to establish this; instead, he located the regions of modern-day Central and South America.

By this time, Columbus' colonists were actively engaged in capturing and selling the natives as slaves and further abusing them daily. Columbus objected to this treatment of the natives and punished the colonists severely which resulted in a charge of tyranny and corruption (as he was interfering with business practices) brought against him in 1499 CE. He and his brother Diego were arrested and sent back to Spain to answer charges. They were acquitted by Ferdinand and Isabella, equipped with new ships, and sent back to the New World.

Fourth Voyage - 1502-1504 CE: Columbus returned with a fleet of 30 ships, 29 of which were lost in a storm off Santo Domingo, to find that the regional governors no longer wanted or needed him there. He was thought to have mismanaged the colonies by defending the indigenous peoples and interfering with the slave trade which had cost the slave traders and the Spanish crown considerable financial loss.

On his own, Columbus explored the islands off Honduras, mapped Costa Rica and other sites, and was sailing on when a storm drove his ship toward Jamaica where it was wrecked. The natives despised him and refused any aid, and the regional governors of the area felt the same and would not send a rescue ship. Columbus finally frightened the natives into assisting him by claiming he would take the great light from the sky if they did not and then accurately predicted the lunar eclipse of 29 February 1504 CE, claiming to have restored the light once help was promised. He and his men were eventually rescued, largely through their own efforts, and Columbus returned to Spain where, in ill health, he died in Valladolid in May of 1506 CE.

Conclusion

Modern-day evaluations of historical figures and events are frequently guilty of the fallacy of presentism – judging the past by the standards and ideologies of the present – and the life and voyages of Christopher Columbus stand as one of the best, if not the best, examples of this. Prior to the publication in 1828 CE of A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus by Washington Irving, Columbus was almost unknown in the United States. His book on Columbus, more historical or romantic fiction than history, was interpreted as a scholarly work on the life and adventures of an intrepid European explorer who had “discovered America” and went on to inform United States' history up to the present day.

Columbus never claimed to have “discovered America” and neither is there anything in his journals or the writings of near-contemporaries to suggest that scholars of his day believed the earth was flat while he proved it was round (it was well known in 1492 CE that the earth was round), nor that he “got lost” while searching for a route to India, landed in some strange place he thought was his destination, and so named the native people Indians. Most, if not all, of the myths commonly cited as history concerning Columbus were the creations of Irving who was only trying to tell a good story.

Irving's Columbus was a brave and noble adventurer who risked his life and that of his crew to extend European knowledge of the world and establish a vital link between the Old World and New. The book was so popular that it informed the decision of U.S. President Benjamin Harrison (served 1889-1893 CE) to proclaim a national day of observance in Columbus' honor in 1892 CE, on the 400th anniversary of Columbus' arrival. The state of Colorado would later be the first to observe this holiday in 1906 CE and other states followed suit afterwards.

The present movement to rename and rededicate Columbus Day in honor of indigenous people is understandable and admirable, but the opposing side, arguing to continue the tradition of honoring him, also has merit, especially when one considers what it meant to Italian-Americans, frequently persecuted in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries CE, to have an "American Hero" defined as "Italian" by Irving and recognized as such by the American majority. It was largely the efforts of Italian-American community groups, in fact, which helped establish the holiday to begin with.

Healing past wounds must begin with a dialogue which recognizes the underlying causes and long-term effects of Columbus' atrocities while also acknowledging his accomplishments. However one judges Columbus in the present day, he was a product of his time who behaved toward non-Europeans precisely as one would expect a 15th-century CE European Christian to do and, unfortunately, far better than the colonizers and conquerors who came to the New World after him.